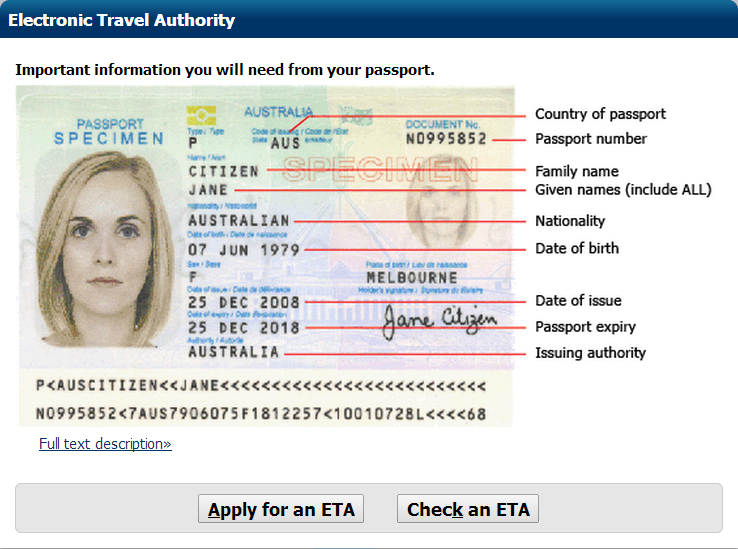

Today I found myself on the website of the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection, looking to apply for a visa. (My Australia “Drafting Clearer Contracts” seminars are next week; go here for links to more information.) While on their website, I noticed the following graphic:

Interesting, I says to myself. In an Australian passport, the day and month of the date of expiry is the same as the day and month of the date of issue. So this specimen passport expires at the beginning of 25 December 2018—the final day is excluded.

By contrast, on my U.S. passport (excuse me if I don’t include a copy!), the day and month of the date of expiration (yes, we use a different word) is a day earlier than in the date of issue. So the passport expires at the end of the day stated for expiration—the final day is included.

In other words, the Australian and the U.S. agencies in question have different policies for stating end points in time. Because we know when the passports were issued, we can figure out at what point in the dates in question expiry/expiration actually occurs.

But imagine instead that we were dealing with a contract that states an end point of a less conveniently neat period. Unless the exact point in time were flagged by a preposition (for example, through), we’d be left to wonder whether the end point is inclusive or exclusive. Or we might opt for one or other interpretation without being aware of the underlying policy.

It’s because of that sort of potential for confusion that I prefer to state a time of day when I state a point in time. Usually, I do so by saying midnight at the beginning or midnight at the end of the day in question.

I am currently in meditation and prayer over how to specify a point in time (point) unmistakably.

Terms like initial midnight, start of business, noon, close of business, and final midnight are uncertain without an interpretive rule, since they can be understood as synonyms for 12:00 a.m., 9:00 a.m., 12:00 p.m. (where “p.m.” is used to signify that the 12:00 o’clock intended is noon), 5:00 p.m., and 12:00 p.m. (where “p.m.” is used to signify that the 12:00 o’clock intended is literally “post meridiem,” i.e., “after noon”).

Apart from other types of uncertainty, each of those listed is open to being read as a one-minute period, as in, “Is it 5:01 yet?” “No, it’s still 5:00 for another twenty seconds.”

It may often be okay to “specify” a period by means of smaller periods where it doesn’t matter whether the big period starts at the start or end of the initial little period and it doesn’t matter whether the big period ends at the start or end of the final little period.

For example, who cares whether a lease whose term starts at “midnight at the start of January 1” starts precisely at the beginning or end of the one-minute period between 12:00 and 12:01? Or whether the term of that lease, said to end at “midnight at the end of December 31” ends exactly at the start or end of either (a) the one-minute period starting at 11:59, or (b) the one-minute period starting at 12:00?

But if it really matters precisely at what point a period starts, ends, or both, I am finding it very difficult to fashion language that is both precise and concise, with or without the aid of an interpretive rule.

For example, consider this possible rule: “When a period starts at midnight on a given day, the period starts at the point that begins that day, and when a period ends at midnight on a given day, the period ends at the point that ends that day.”

Even were that formulation bullet-proof, and I’m not sure it is, it’s fairly long, and it only covers midnight.

I suppose a more general rule of interpretation could be this: “Whenever a period of time in this agreement begins at a clock time stated in hours and minutes, the period begins at the point at the start of the one-minute period described by the stated clock time, and whenever a period ends at a clock time stated in hours and minutes, the period ends at the point at the end of the one-minute period.”

Even if that long formulation is bullet-proof, and I’m not sure it is, what about periods expressed in days, weeks, months, and years? How cumbersome to fashion an interpretive rule for each such period.

Maybe a “global” interpretive rule would be this: “Whenever the starting point of a period of time in this agreement is expressed as a smaller period of time, the starting point is the point at the start of the smaller period of time, and whenever the ending point of a period of time in this agreement is expressed as a smaller period of time, the ending point is the point at the end of the smaller period of time.”

All the foregoing is an attempt to grapple with the commandment, “When an agreement specifies a period of time, expresses precisely the points that start and end the period.”

I submit that it’s hard to comply with that commandment, risky to rely for compliance on a “convention” that exists outside the contract itself, and difficult to comply without using an explicit interpretive rule, either on site or in a provision specifying interpretive rules.

Sorry for the long post, especially if I have overlooked a compact and easy solution.

I can’t help thinking that this is why somebody invented the 24-hour clock. If you want something to begin at the midnight that starts a day, you’d say “0:00” or “zero hours,” and when you want it to end on the midnight that ends a day you’d say “24:00” or “24 hours.” Is that too simple a solution for the legal mind to handle?

With all humility, I don’t think that addresses, let alone solves, the problem, which is that, say, “1700 hours” isn’t unambiguously a point, because it allows the dialogue: “Is it 1701 hours yet?” “No, it’s still 1700 for another 20 seconds.” Same problem with 0:00 and 24:00. A digital clock that shows hours and minutes shows each minute for 60 seconds, so that time isn’t a “point” but rather a “period” and further verbiage is needed to nail down which point the drafter means. I think my post was a little congested, but that’s what I was aiming at.

Hmmm, guess I didn’t realize that “the problem” was defining (much less locating) a “point in time” rather than a useful way to describe when something happens. First of all, while spacetime might conceivably have points, which are unhelpfully inextricably intertwined with their temporal location (have to consult Einstein on that), I don’t think time by itself does. Second, I doubt that God wears a digital watch. Third, does the need for an infinitesimally precise subdivision of time and space (do consult Lewis Carroll on that one) mean that lawyers now need instruction in quantum physics? And mainly Fourth, I’d love to see a case that hangs on whether something happened *at* or *by* a stated time if it happened in the second between midnight and 0 (or 24):00:01 or, where a time was stipulated only to the minute, the minute after. “The stroke of twelve” is an interesting concept: twelve has twelve strokes, and I believe traditionally all twelve have to go by for the moment to have passed.

So many angels, so small a pinhead!

“Ah, my Lords, it is indeed painful to have to sit upon a woolsack which is stuffed with such thorns as these!”

One hesitates to fence with one who has Sir William Gilbert at his beck, but the same issue arises with larger units of time, such as the ten years at issue in the Australian passport (see Josh’s post).

Does the passport expire at the beginning or end of 25 December 2018, or at some point between the two? The passport itself doesn’t say. One must consult unspecified external aids.

Josh points out that the relevant regulation says that (1) the passport expires at the end of the expiry day, but (2) a passport is not valid for more than ten years.

Something has to give. Either the passport is valid for more than ten years, or it isn’t valid till midnight at the end of the day of issue.

A contract drafter shouldn’t allow that much uncertainty into the description of a contractual period.

Case law abounds on the meaning of various prepositions, “entire days,” “excluding the first terminal day but not the last,” and similar issues, all dedicated to determining the points — points! — at which relevant periods begin and end.

All periods of time, not just short ones, begin and end at points. Good thing there are lots of angels.

The challenge for a contract drafter is to describe such points (1) precisely, (2) concisely, and (3) if possible, without requiring the reader to consult any court case or other authority, convention, or tradition (twelve bells) outside the contract.

It may not be Einstein-hard, but it’s hard, and it’s everyday stuff. I note that MSCD devotes a chapter to it.

Sure, although there’s always the possibility that Australian passports are valid for 10 years plus a day.

Looks unclear, actually – the relevant regulation (the “Australian Passports Determination 2005” regulation – http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2013C00149) is confusing. It indicates both that:

– a passport ceases to be valid at the end of the day specified in the passport as the date of expiry (s. 5.1(1))

– the maximum period for which a passport may be valid is … for a passport issued to an adult — 10 years.