I recently noticed a LinkedIn post by Saul Lieberman. It’s about the ostensible differences between indemnify, defend, and hold harmless. In a comment (here) to his own post, Saul mentions Chesterton’s fence. I was happy to be reminded of it.

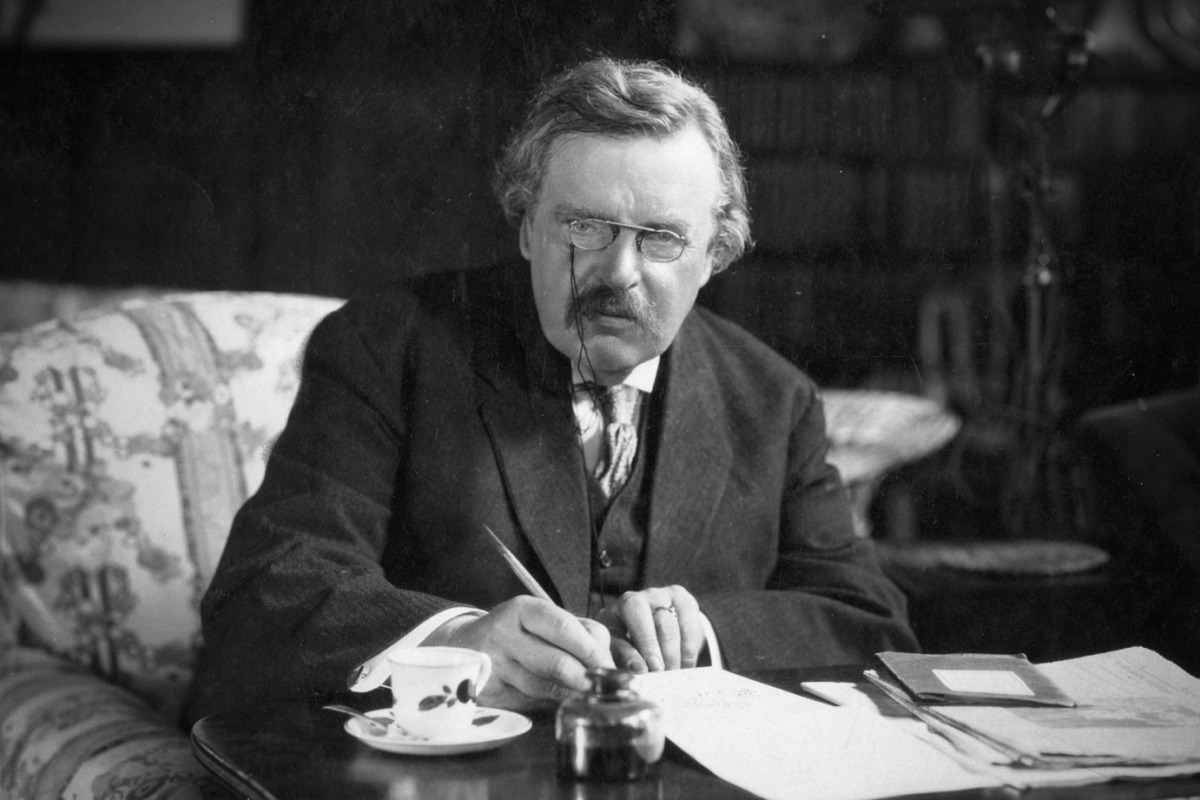

“Chesterton’s fence” is the name given a parable offered by G.K. Chesterton (best known now as author of the Father Brown stories) in his 1929 book, The Thing, in the chapter entitled “The Drift from Domesticity”:

There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

That has been boiled down (here, for example) to “We shouldn’t be too quick to dismiss things that seem pointless without first understanding their purpose.”

Why did Saul invoke Chesterton’s fence? Because the state of the contracts process, and the state of contracts prose, suggest that Chesterton’s fence has been a guiding principle in mainstream contract drafting.

Since people started drafting contracts, the process has relied on copy-and-pasting from precedent contracts and templates of questionable quality and relevance. And how have we learned to draft? By copy-and-pasting! That’s all you know, so you accept as the norm whatever you’re copy-and-pasting. (In this 2014 blog post, I analogize it to “the think system” used by “Professor” Harold Hill in the play (and movies) The Music Man, with children intoning repeatedly, without bothering with instruments, the melody of Beethoven’s Minuet in G—”Lad-di-da-di-da-di-da-di-dah …”)

Life is further complicated by the urge of the legalistic mind to justify, post hoc, chaotic contracts usages. That sad urge is still with us—check out the article Saul links to in another comment to his post.

It follows that if you learn by copy-and-pasting, you likely wouldn’t have any basis for removing a given fence. In fact, the conventional wisdom might well offer reasons for leaving it up.

On the other hand, nothing stops you from adding another fence! The result is that stuff gets into contracts, but once it’s there, it rarely leaves. After all, whoever added it in the first place must have known what they were doing!

If you’re looking for help in deciding, for purposes of saying clearly and concisely whatever you want to say in contract, which fences you can safely to take down and which fences to add, you might want to check out A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting. 🙂

(I got the photo at the top of this post from this page of the Society of G.K. Chesterton. I thought they wouldn’t mind, but if they do, please contact me!)

“Adding another fence” — great response.