A couple of months ago I did this blog post about the redundant reference-point exception in the bringdown condition. Today we revisit the bringdown condition to consider an issue involving how the bringdown condition is modified by materiality.

The bringdown condition allows one side to use inaccuracy in the other side’s statements of fact (traditionally referred to as representations and warranties) to relieve it of its obligation to close. A seller would prefer to have the buyer’s bringdown condition be subject to a materiality qualification. That can be accomplished in one of two ways. You can have the condition require that the statements of fact be materially accurate or accurate in all material respects (they mean the same thing). Or you can use the phrase material adverse effect or material adverse change (they too mean the same thing).

Let’s consider the latter option. Here’s the relevant part of the bringdown condition from the merger agreement at issue in the Delaware Court of Chancery’s 2018 opinion in Akorn, Inc. v. Fresenius Kabi AG (PDF here):

The representations and warranties of the Company … (ii) set forth in this Agreement … shall be true and correct … as of the date hereof and as of the Closing Date with the same effect as though made as of such date … , except, in the case of this clause (ii), where the failure to be true and correct would not, individually or in the aggregate, reasonably be expected to have a Material Adverse Effect.

This is the standard way to qualify the bringdown condition by MAE, but the semantics don’t work. The exception applies unless the inaccuracy results in an MAE. It doesn’t make sense to think in terms of an inaccuracy resulting in an MAE. Instead, if, say, a “financial statements comply with GAAP” statement of fact is found to have been inaccurate, the circumstances giving rise to that state of affairs—and not the inaccuracy itself—constitute an MAE. In the usual scheme of things, the only consequences of inaccuracy would be that the buyer doesn’t have to close or the buyer has a claim for indemnification.

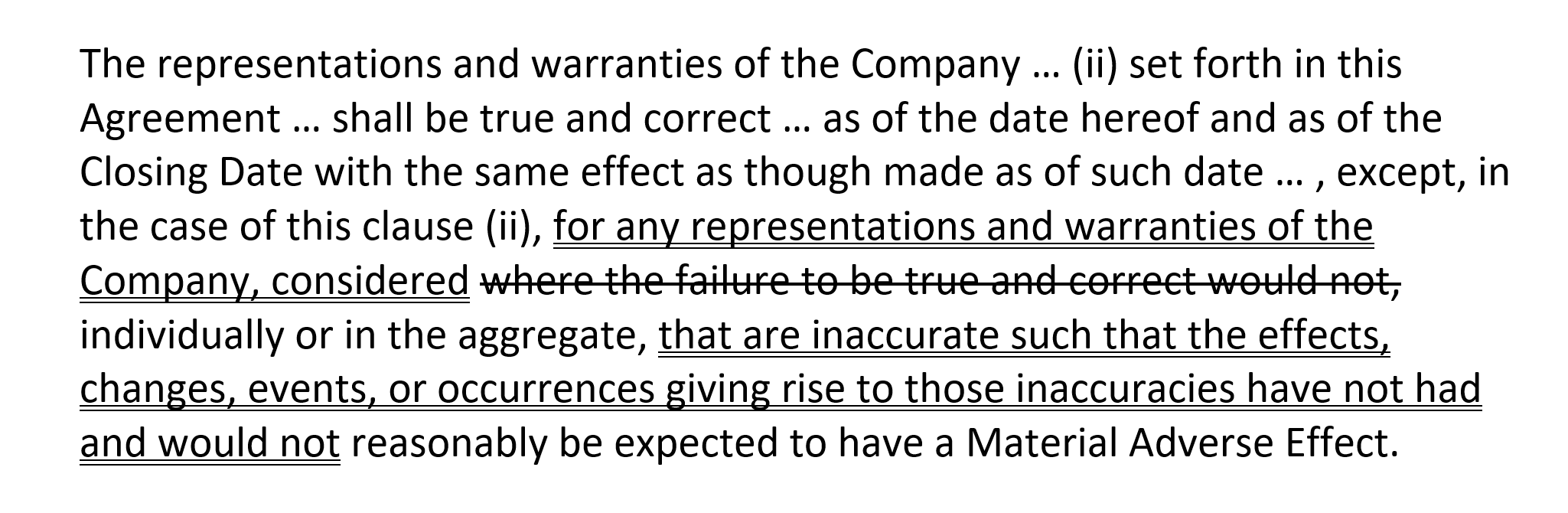

I first pointed this out in my book The Structure of M&A Contracts. And because I couldn’t get it to make sense, I said don’t use MAE to qualify the bringdown condition. But while working on my forthcoming article on the ambiguous material, I took the opportunity to ask some knowledgeable people about this, and I figured out the intended meaning, namely the meaning Vice Chancellor Laster applied in Akorn, starting page 195 (if I understand it correctly). Using the Akorn bringdown condition, here’s a better way to say it:

(I’ve stuck with the traditional language instead of using my own version of the bringdown condition. And the new language tracks language used elsewhere in the merger agreement at issue in Akorn.)

As a sanity check, I asked Glenn West what he thinks. He said, “I think your wording is clearer. I think Vice Chancellor Laster interpreted the other wording to say what your wording now more clearly says.” If Glenn thinks it’s clearer, that makes me feel more comfortable about my position.

So what’s an M&A practitioner to do? If your bringdown condition is qualified by MAE, it would be a good idea to revise it consistent with my revised version. But in M&A, change is scary. A glance at any acquisition contract would tell you that being clear and concise not only isn’t a priority, it would appear to be a liability, as it involves change.

I don’t do mergers and acquisitions, and may also be thick, but all I see in the revised provision boils down to this:

‘If any representation or warranty of the Company in this clause (ii) is inaccurate when made, on the Closing Date, or both, for any cause reasonably likely to have a Material Adverse Effect, [the Buyer need not close and may seek Indemnification]’.

The bracketed words aren’t in the original; they stand in for whatever happens if the accuracy condition goes unmet.

The only other change I would consider is to specify when on the closing date the representation must be correct.

For example, if a representation was that a certain line of credit was at zero, and it was at zero at signing, but at EU 40 000 at 9:00 a.m. on the closing date and a belatedly alert somebody paid it down to zero before 10 a.m., was the condition met or unmet on the closing date? (Only if unmet does the material adversity analysis start.)

But that’s my old song about if you mean a point, don’t describe a period. –Wright

It seems to me that the provision is mixing two things that should be separate: truth of the reps and warranties at closing and the occurrence of an MAE. The MAE should be an independent closing condition, and if that’s the standard, then the truth of the reps should probably be narrowed to the fundamental reps or some other segment in terms of closing while preserving the indemnification remedy for the rest subject to the MAE exception.

From the buy-side, you’d want any inaccuracy in the reps to give you the right not to close so that you could potentially negotiate a bigger/better solution than what you might eventually get with indemnity, such as no basket or additional escrow.

So, the scheme should be:

1. Fundamental reps true at closing.

2. No MAE / No MAE that makes a non-fundamental rep false at closing.

Fundamental reps is a term of artsy – meaning there’s no solid definition, but it’s used to identify reps that survive beyond the normal indemnification period, either to the statute of limitations or in perpetuity. Things like title, taxes, and authority feel so important that even sellers understand not being let off the hook if a problem doesn’t show up for the first 18 months. The core of the list is stable, but the edges are fluid across deals.

Thanks for this, Rick. My aim in this post was just to point out the semantics glitch. You’re looking at how best to qualify the bringdown condition by MAE; I don’t have the time to look into that at the moment. If I do a second edition of The Structure of M&A Contracts, that would be the time to look into it.

Hey, we can’t let you have all the fun!

Plus, we’re supposed to be doing the work to build on what you’ve spotted and fixed, right?