Thanks to longtime tipster Steven Sholk, I learned of the recent opinion of the First Circuit in Dahua Technology USA, Inc. v. Feng Zhang (here).

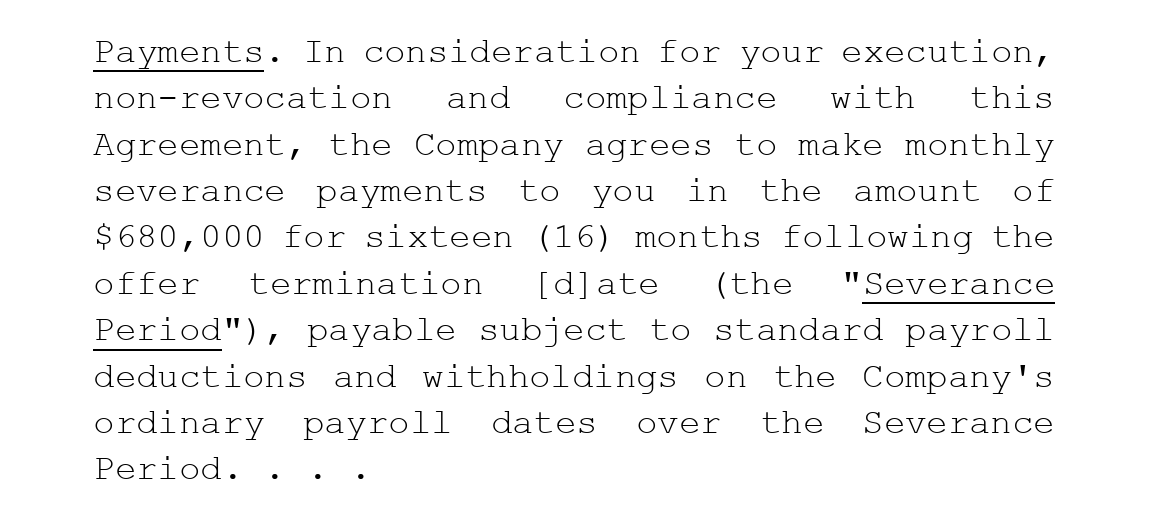

The language at issue is in the image at the top of this post, but the key component is “the Company agrees to make monthly severance payments to you in the amount of $680,000 for sixteen (16) months following the offer termination [d]ate.” Zhang alleged that Dahua breached its obligation to pay him severance of $680,000 per month for each of sixteen months, for a total of $10.2 million. Dahua argued that the parties only intended Zhang to receive total severance of $680,000, paid in 16 monthly installments. The district court entered judgment for Zhang in the amount of $10.2 million; the First Circuit vacated the judgment, holding that the provision was ambiguous, and remanded the case to the district court.

The First Circuit’s decision is correct but problematic. Here’s the heart of its analysis (citation omitted):

The district court analyzed just the severance-payment provision and concluded that it supported only one meaning: that Dahua was to make sixteen severance payments to Zhang over the course of sixteen months, each in the amount of $680,000. Put differently, the district court adopted a reading that construed the word “monthly” as relating forward to modify “severance payments,” thus making “monthly severance payments” the direct object of the provision. “[I]n the amount of $680,000,” in turn, modifies that direct object, telling the reader that each monthly severance payment should be $680,000.

While that is a reasonable way to read the severance provision, it is not the only plausible reading. The text also supports a construction in which “monthly” relates backwards to modify “make,” thus making “severance payments” (as opposed to “monthly severance payments”) the direct object of the provision. When read in this manner, it is unclear whether $680,000 describes the monthly or total severance payment, as one can just as well make “severance payments” in the total amount of $680,000 or monthly payments in that amount. The immediate context does not resolve that ambiguity: “make monthly” and “for sixteen (16) months” indicate the frequency and duration of the payments, respectively, but neither phrase clarifies the intended amount.

The court appears to be saying that monthly operates as both an adjective (monthly severance payments) and an adverb (make monthly), and which alternative you opt for affects meaning. I see no basis for that—I find their suggesting bewildering. I suspect that these judges, like many, aren’t students of linguistics and so feel free to improvise. (See this 2020 blog post entitled Many Judges Are Bad at Textual Interpretation. What Do We Do About It?)

Here’s my take: Whenever you attribute a quantum to a collection of more than one item without specifying that the quantum applies to each individual item or, conversely, applies to all items in the aggregate, you leave open whether the quantum applies to individual items or to the group. Here are four examples:

- five toads weighing 250 grams

- four doubloons worth $6,000

- two strawberry creme donuts (800 calories)

- six monthly shipments of penicillin (10,000 vials)

The greater the number of items, the clearer it should be whether the drafter intended the quantum to apply to each individual item or to the group.

To avoid this kind of confusion, say either each or in the aggregate, depending on the meaning you intend.

I’ve not encountered this kind of ambiguity previously. In terms of the taxonomy of ambiguity, I suggest it fits in that part of “ambiguity of the part versus the whole” that addresses the ambiguity of plural nouns. In five years or so, look for a section on it in the sixth edition of A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting. 🙂

Hi Ken,

I agree with your assessment, but can you clarify why you think the court was correct? You mentioned they came to the correct conclusion with the wrong rationale. I agree, but I’m curious as to your thoughts why. For some reason, it doesn’t read as ambiguous to me as “five toads weighing 250 grams” but I admit I am struggling to articulate why I feel that is the case.

Thank you!

RB

I think the reason the First Circuit decision is correct is that its remedy is the proper one for a case of ambiguity. The court properly didn’t reach a conclusion as to which interpretation was correct, but sent it back down for more fact-finding.

Oh BTW the provision of the contract on paying salary has its own quiddity that nobody discussed in this case: the employee, now consultant, would be paid $240K in biweekly installments of $10K for two years. But of course if the payments were biweekly the total after two years would be $260K. So, sub silentio, the court “reformed” the contract to read “semi-monthly” rather than biweekly.

Hmmm. Seems to me the best way to resolve the ambiguity would be to look at the background. In other words make an exception to the discredited parol evidence rules. It’s likely to make things completely clear