I noticed that the National Security Agency and the Department of Homeland Security have finally acknowledged that merchants who use images and names of those agencies on parody merchandise aren’t violating any federal laws. How big of them. Go here for Public Citizen’s press release.

But what’s of particular interest to pointy-headed me is the settlement agreement between the agencies and Dan McCall, the activist who pursued this matter. (Go here for a PDF.)

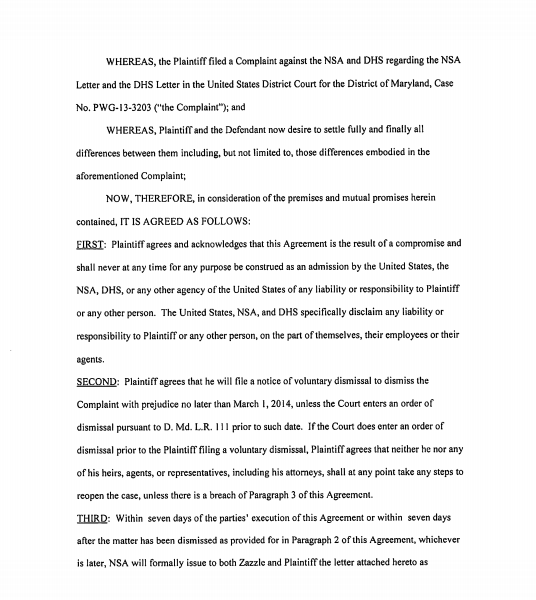

It is, or course, full of traditional contract legalese, from the all-capitals in the introductory clause (“THIS SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT AND GENERAL RELEASE”) to the archaic format of the dates in the signature blocks (“this 13th day of February”). But that’s hardly exceptional.

What caught my eye is the enumeration used for the sections. Instead of using arabic digits with section headings, the sections are enumerated “FIRST:” through “NINETEENTH:”, without descriptive headings.

That looks like the enumeration used in old-fashioned pleadings. I suspect that one can file this under “When litigators draft contracts.”

The excerpt you give is loaded with points of interest, as you said. Here are a few:

1/ Is it “Plaintiff” or “the Plaintiff”? Inconsistent usage.

2/ “[S]hall never…be construed as an admission.” Unstated by-agent; attempt to bind nonparties?

3/ “Plaintiff agrees and acknowledges”:

(a) Unilateral agreement by the plaintiff? Doesn’t the defendant also agree to the same thing? If not, with whom is the plaintiff agreeing on this point?

(b) Read together with the language of agreement in the lead-in, this wording provides that the parties agree that the plaintiff agrees.

(c) Why use the term “acknowledgment” at all? Why not just say “this agreement is the result of compromise and is not an admission”? The simple statement should bind courts and all other nonparties with the same force as a definition or an agreed rule of interpretation.

4/ How odd to see no exception from the liability disclaimer for the defendant’s obligations under the settlement agreement itself. If the parties agree that one party has no duties to the other, doesn’t that falsify the statement of consideration and make the whole agreement illusory?

From a litigator’s perspective it is not uncommon for litigants to draft agreements with the instant case style at the top. But that raises the question as to whether it was actually filed with the court—which would have been

inappropriate, in my opinion. Personally, I do not like the practice of including the style on settlement agreements as doing so tends to take away from the ability of such agreement to “stand on its own,” sole and separately from the instant litigation.

And I spotted some other phrases that irk me. Specifically, that the government “reserves the right to enforce section ____ in the future.” How absurd! This isn’t the first time I have seen such language. In fact, it is quite common—usually in the course of a settling defendant “reserving its rights.” The compulsory counter-claim rule applies, if at all, irrespective of contractual language. Of course, counter-claims not ripe during the litigation can never be estopped by mere inference from a settlement document. Thus, my irritation at them.

Keep up the fine work of attempting to bring clarity to the world of contracts.