Glenn West has been pumping out articles so fast that I haven’t kept up. I’ve started looking at the backlog; if I have anything to add, I’ll do so.

That’s what I’m doing now, because this post was inspired by Glenn’s article Transactional Lawyering as an Art: When Saying Less Is More Than Enough, Business Law Today (11 Feb. 2025). It discusses a 2024 opinion of the Delaware Chancery Court, Comcast Cable Communications Management, LLC v. CX360, Inc. That opinion involves a dispute over a master services agreement between Comcast and CX360. Or more specifically, whether CX360 had been entitled to terminate the contract.

Like the Delaware Chancery Court, Glenn says the sentence at issue in this dispute is ambiguous. Glenn then suggests that leaving the sentence ambiguous might have been legitimate, given that Comcast had discouraged changes to the contract.

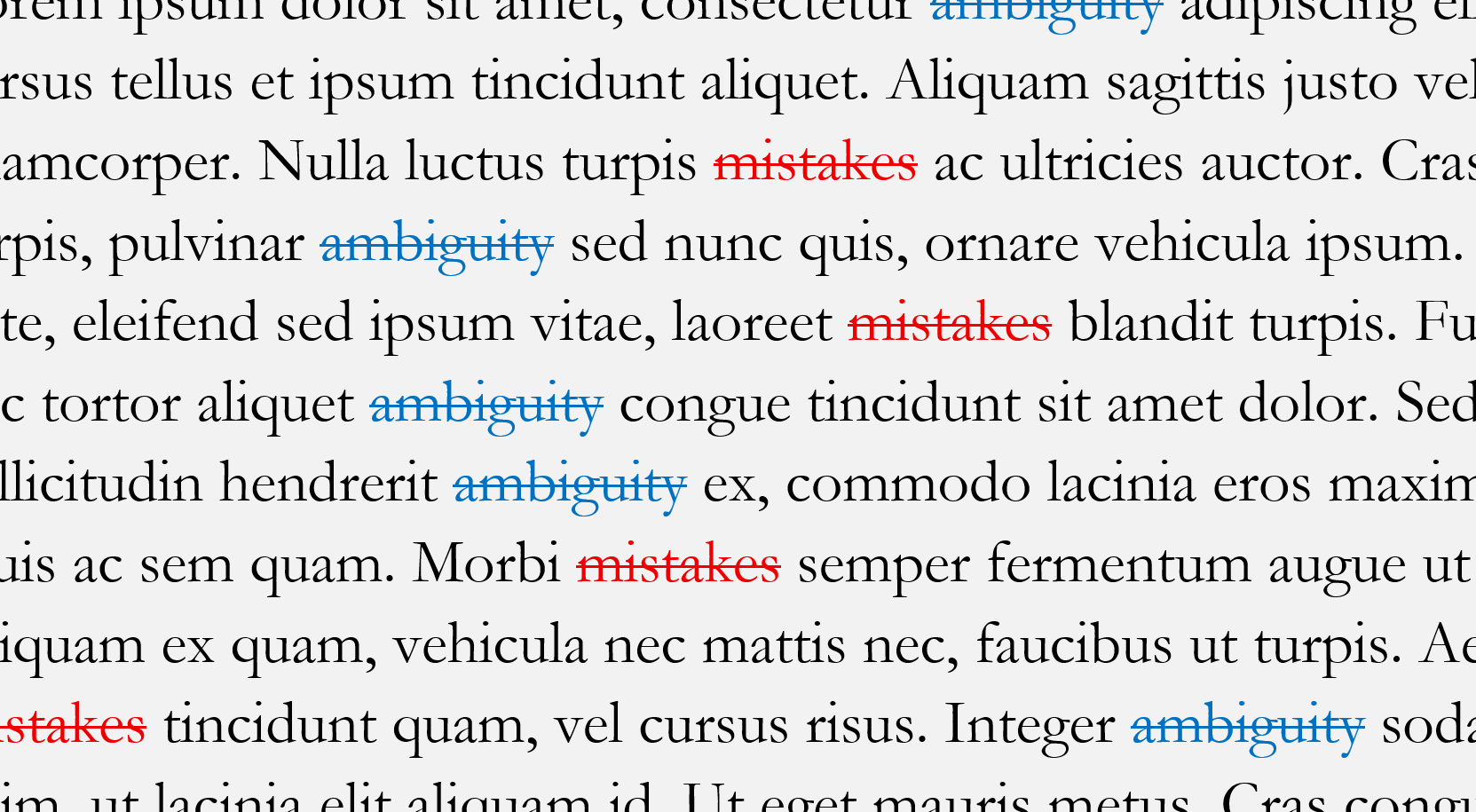

My take on this dispute differs from Glenn’s in three respects. First, the sentence at issue isn’t ambiguous—instead, one part of the sentence conflicts with another. Second, that conflict should have been fixed. And third, even if the sentence had been ambiguous, ambiguity should be eliminated from contracts. In what follows, I’ll explain how I reach those conclusions.

The Dispute

Here’s what was originally in the contract:

Comcast may, at its election, terminate this Agreement and/or any [statement of work] without cause on ninety (90) days written notice to the Vendor.

Here’s how CX360 marked it up:

ComcastEither party may, at its election, terminate this Agreement and/or any SOW without cause on ninety (90) days written notice to the Vendor.

Apart from “party” subsequently being given a capital P, that’s how that sentence reads in the signed version of the contract.

Here’s Glenn, quoting the court (footnotes omitted):

Absolute clarity for CX360, of course, would have required one additional change—i.e., crossing out “Vendor” and replacing it with “other party.” As written, the provision technically requires CX360, if it is the terminating party, “to notify itself upon [exercising its right of] termination.” And, as was pointed out in the subsequent dispute, “[i]t would be absurd to require CX360 to provide notice to itself rather than to Comcast.” But that change was never made or suggested.

…

Comcast’s position was that CX360 did not actually have a termination right—only Comcast did. And that position was based upon the alleged ambiguity created by the language at the end of the otherwise mutual right to terminate—i.e., the language providing for the right to terminate to be exercised by providing “‘written notice to the Vendor’—i.e., CX360.” But according to Vice Chancellor Will, “sloppy drafting does not necessarily create ambiguity.” The only ambiguity here was to whom notice was due, “not the substantive termination right afforded to ‘[e]ither Party.’” Indeed, according to Vice Chancellor Will, “Comcast’s argument that the ‘notice to the Vendor’ language means only Comcast could terminate for convenience would make CX360’s bargained-for termination right ‘illusory or meaningless.’”

This was clearly the right outcome.

Here’s the lesson that Glenn took from this dispute:

Whether CX360 considered making a further clarification when it was marking up the original form MSA, and made a calculated decision that requesting fewer changes was strategically the best course, is not known. This “less was enough” approach certainly worked out for CX360, whether it was intentional or not—and who knows if CX360 would have obtained the mutual right to terminate for convenience had it pursued absolute clarity in the context of bidding for the privilege of providing Comcast’s IVR services and being told that changes to the form would be viewed negatively.

Transactional lawyering is more of an art than a science. But make no mistake, words matter; and sometimes the strategically best choice is fewer words, even if those words lack absolute clarity.

Tolerating a Mistake?

But not changing “Vendor” to “other party” doesn’t create an ambiguity. Instead, it’s creates a conflict between the reference to “Vendor” and the preceding reference to “Either party”—the sentence as written doesn’t make sense. And it seems that Comcast didn’t notice the “Either party” element of the sentence or didn’t realize its implications.

I’m not surprised that the Delaware Chancery Court mistook for ambiguity what was a conflict: many who work with contracts have an uncertain grasp of the sources of uncertain meaning in contract language. (See my 2016 article in the Michigan Bar Journal for an overview of the sources of uncertain meaning.)

But the label applied to this misadventure in drafting isn’t what caught my eye. Instead, it would have been bizarre for CX360 to intentionally introduced the conflict by changing the first part of the sentence and not making a conforming change later in the sentence. Yet that’s what Glenn suggests when he says that CX360 might have “made a calculated decision that requesting fewer changes was strategically the best course.”

And more generally, it would be odd for a party that tries to discourage changes to its form contract to quibble about a counterparty seeking to fix a mistake, whether the mistake was caused by the party responsible for the form or was introduced by the counterparty (as in this dispute). (Whether it’s a good idea to keep quiet about a drafting mistake by the other party that works to your benefit is a different matter—neither Glenn nor the Delaware Chancery Court suggests that that’s what went on in this dispute.)

Tolerating Ambiguity?

Although it turns out that ambiguity wasn’t at issue in this dispute, what about tolerating ambiguity in a contract, whether it’s introduced intentionally or was unintentional but is spotted by the other party? (Because ambiguity wasn’t actually at issue, Glenn’s article doesn’t address this.) For two reasons, I think it’s rare that that occurs.

First, often when people refer to ambiguity what they have in mind is vagueness. Whereas ambiguity is a function of alternative possible meanings, vagueness is a function of meaning being based on what would be reasonable in the circumstances. Intentionally introducing ambiguity is arguably unethical, and courts don’t like it—they tend to construe ambiguity against the drafter. It follows that looking to benefit from ambiguity introduced by the other side is also questionable. By contrast, being vague—that’s achieved by using words like promptly and reasonably—is an essential tool of the drafter, to be used carefully when being precise doesn’t make sense.

And second, after having studied ambiguity in contracts perhaps more than any other mortal, I think that the simplest explanation for ambiguity in contracts is that people don’t see it! It’s subtle. Unless you’ve gone to the trouble of studying ambiguity in contracts, it’s unlikely you’ll spot it.

Do some contract parties seek to benefit from ambiguity, whether the ambiguity was created by them or by the other side? And do some of those that do reap a benefit from doing so? Maybe. But I wouldn’t join them. If you feel you have to be underhanded to be satisfied with a deal outcome, maybe you should rethink your priorities.

Scholarship!

Glenn and I go way back. Why would I write a blog post exploring his analysis of the implications of a bit of contract language? Well, because I like to think that’s how healthy scholarship works.

In his article, Glenn says “the job of a transactional lawyer is not for the faint of heart.” The same could be said of the task facing those who write in depth about contract language—few have the stomach for it.

Like scholarship generally, my writings are an invitation to the world to point out stuff I got wrong or stuff I missed, but usually the reaction is … silence. I’m in the scholarship business because I want this small corner of our civic society to function better than it does. If others chime in in an informed and constructive way, I welcome it. I know Glenn feels the same way. As I note in this LinkedIn post, Glenn recently published in the University of Miami Law Review an article that politely takes issue with another article in the same issue.

Glenn focuses on what you say in a contract, I focus on how to say clearly and concisely whatever you want to say, and neither of us can claim to be the equal of the other in their sphere of inquiry. Vive la différence! But there’s a fair amount of overlap between those two spheres, so there’s plenty scope for each of us, in a neighborly way, to look over the fence that separates us and offer comments.

OK, since you seem to be suffering a bout of sedatephobia, I’ll say that I agree with your evaluation. Mistakes like this happen often, usually as a function of “universal replace” commands entered in response to a comment from a client or the predilection of the lawyer to “mutualize everything.” I can’t imagine that this was the only place in the agreement where Comcast reserved remedies just for itself.

Astute observation!

I find it difficult to believe that Comcast would accept that the right to terminate could be changed to be mutual, but push back if the reference to Vendor was changed. Glenn’s suggestion sounds unlikely to me.

It looks to me like a simple (mutual) mistake. From an English law perspective, the action of the judge looks to me like rectification of the contract, even if he didn’t say so. My guess is that 9 times out of 10, an English judge faced with that sentence would simply rectify the wording to replace Vendor with the other party, or would say that Comcast was estopped from denying that the remedy was mutual. From the brief extract you have given, it is difficult to understand what plausible argument Comcast could present for a different interpretation.

Ken,

These words coming from a jurist are the best thing I will read all day:

“…sloppy drafting does not necessarily create ambiguity.”