A force majeure provision in a contract expresses that if something sufficiently bad happens that isn’t under a party’s control, it would be appropriate to suspend performance.

A force majeure provision in a contract expresses that if something sufficiently bad happens that isn’t under a party’s control, it would be appropriate to suspend performance.

Given the coronavirus pandemic, a handful of readers suggested that I write something about force majeure provisions. Initially I demurred—I thought I’d already had my say in previous blog posts. Also, I wasn’t inclined to join the dismal tide of law firm newsletters on the subject.

But after revisiting the subject in my capacity as advisor to LegalSifter, I was reminded that I did have something to say. But I won’t attempt to cover the topic comprehensively—that would take too long and would likely be too dull. Instead, I’ll focus on stuff that has caught my attention. Then I’ll summarize what matters for contracts you’ve already signed and what matters for contracts you have yet to sign. I’ll limit myself to my experience with U.S. contracts, but much of this should be relevant in other jurisdictions.

Why the Phrase “Force Majeure”?

Here’s the Black’s Law Dictionary definition of force majeure:

force majeure (fors ma-zhər) [Law French “a superior force”] (1883) An event or effect that can be neither anticipated nor controlled; esp., an unexpected event that prevents someone from doing or completing something that he or she had agreed or officially planned to do.

The phrase force majeure might seem annoyingly legalistic. One could use instead a defined term such as Interruption Event or Excusable Downtime, or even something as custom-made as Country Risk Event. But such alternative defined terms are often used to express a broader meaning that incorporates the concept of force majeure, or a different meaning, so using one of those alternatives instead of force majeure could create confusion.

In this 2013 blog post I say that abandoning the phrase force majeure would be more trouble than it’s worth. (And if you think force majeure is annoying, be grateful for small mercies—the Latin alternatives vis major and casus fortuitus are out there.) But if you’re scouring your existing contracts looking for force majeure provisions, be on the lookout for improvised synonyms.

Don’t Expect to Always See a Label

Whatever terms of art or defined terms are used to express the concept of force majeure, it’s often expressed without using any such label. Here’s an example, plucked at random from EDGAR:

So if you look for this kind of provision just by looking for force majeure or some equivalent term, you’ll miss stuff. It’s essential you also look for structures repeatedly used to express the underlying meaning. With my help, LegalSifter has devised software to do just that. (More about that below.)

Once you know what to look for, you’ll find force majeure provisions—whether or not they use that term—in unexpected places. For example, in termination provisions. This is from a hotel agreement:

You also see the concept expressed in the definition of Material Adverse Change. That would result in the concept underlying force majeure having implications for statements of fact, conditions, obligations, and termination provisions. See MSCD ¶¶ 9.41–.47.

You also see the concept expressed in the definition of Material Adverse Change. That would result in the concept underlying force majeure having implications for statements of fact, conditions, obligations, and termination provisions. See MSCD ¶¶ 9.41–.47.

Why the Parade of Horribles?

The most distinctive feature of force majeure provisions is the list of events or circumstances that constitute examples of what might constitute a force majeure event. Each of the three extracts above contains such a list. I’ve seen it called “the litany” and “the laundry list,” but I think of it as the parade of horribles.

For several reasons, the parade of horribles is roll-your-eyes counterproductive.

Ascribing significance to exactly what is included in the parade of horribles is to misconstrue its function. If one drafter includes solar flares and avalanches in the parade of horribles and another includes terrorism and tsunamis, it’s highly likely they do so not because those perils are particularly relevant to that transaction. Instead, the parade of horribles represents a flailing attempt to capture that you wish to include all the bad things!

But the world is sufficiently brutal and capricious that it isn’t remotely realistic to encompass in the parade of horribles every bad thing that isn’t within a party’s control. Drafters try anyway, because the legal profession’s reflexive reaction to semantic uncertainty is throw words at it. With the parade of horribles, it’s to no avail.

And thanks to the copy-and-paste urge and the legalistic mindset, what is thrown into the parade of horribles can seem quaint. Act of the public enemy. Pestilence. Civil commotion. Peril of the sea. And of course, act of God.

The Ever-Growing Parade of Horribles

Once you start throwing words at the parade of horribles, for three reasons it’s hard to stop.

First, a parade of horribles might be a finite list, lacking any suggestion that other events or circumstances might be included. Here’s an example:

With such a list, you shouldn’t be surprised if a court limits you to what’s in the list. See, e.g., Kel Kim Corp. v. Cent. Markets, Inc., 70 N.Y.2d 900, 902–03 (1987) (“Ordinarily, only if the force majeure clause specifically includes the event that actually prevents a party’s performance will that party be excused.”) That would encourage a drafter to pad their list.

But the elements of the parade of horribles are usually offered as examples, either by introducing the list with include or including or by tacking on a catch-all. (Here’s an example of a catch-all: “or any other cause not enumerated herein but which is beyond the reasonable control of the Party whose performance is affected.”) That leads to the second problem: listing examples creates an ejusdem generis problem. (Ejusdem generis is the principle of interpretation that holds that when a general word or phrase follows a list of specifics, the general word or phrase will be interpreted to include only items of the same class as those listed.)

So a court might say that, for example, you included only terrestrial events in your list, so the force majeure provision doesn’t cover solar flares. That’s paradoxical—if force majeure provisions are intended to capture the unexpected, why refuse to consider something to be a force majeure event if it doesn’t resemble what’s in the parade of horribles? In any event, the practical result of this approach is that it gives drafters another reason to make their parade of horribles ever longer.

And third, there’s caselaw to the effect that to fall within the scope of a catch-all, something has to be unforeseeable, whereas if something is listed in the parade of horribles, it need not be unforeseeable. That too gives drafters an incentive to throw everything and the kitchen sink into the parade of horribles. (I discuss that in this 2018 blog post.)

So the parade of horribles not only doesn’t make sense, it also clogs up the works.

The Fragility of Elements of the Parade of Horribles

Even if the parade of horribles includes an event or circumstance that is relevant, you’re still condemned to vagueness.

Consider earthquake. It seems straightforward, but earthquake too is vague. At what point does an earthquake matter for force majeure? Presumably not if it just rattles your teacups.

An aggravated version of the problem afflicts elements that don’t describe the nature of an event or circumstance but instead refer to the result. For example, disaster. You’re in effect trying to give meaning to all the bad things by saying it includes anything really bad.

It’s possible to build in a measure of certainty by tying an event or circumstance to objective criteria. For example, pandemic is a vague word—a what point does an epidemic become a pandemic? You could circumvent that by having something be a pandemic if the World Health Organization declares it to be a pandemic, as it did on 11 March 2020 with coronavirus.

Such potential islands of certainty aside, assessing whether an element has been triggered involves vagueness—sticking your finger in the air and deciding whether it’s bad enough.

Getting Rid of the Parade of Horribles

Given the futility of the parade of horribles, I have omitted it from my force majeure language. (The most recent iteration is in this 2013 blog post.) You can’t escape the vagueness, so I embrace it by simply referring to any event or circumstance, offering no examples that might encourage a court to arbitrarily limit the provision. I leave it to the parties or the courts to figure out what would be reasonable in the circumstances. That’s what they’d have to do anyway.

Consider Using Carveouts

If you wish to exclude certain events or circumstances from the scope of force majeure, you could omit them from the parade of horribles, but it would be much clearer to exclude them explicitly, using carveouts.

You could exclude, for example, a strike or other labor unrest that affects only the nonperforming party, an increase in prices or other change in general economic conditions, or a change in law.

Whether a carveout makes sense for a transaction depends on the circumstances. For example, you might decide that you draw the line at assuming the risk of an event or circumstance occurring. Or you might include in a carveout something that courts likely would not consider a force majeure event, on the principle that it’s better to avoid a fight than win a fight. Whatever the carveout, think it through.

Keeping Deal-Specific Risk Separate from Free-Floating Risk

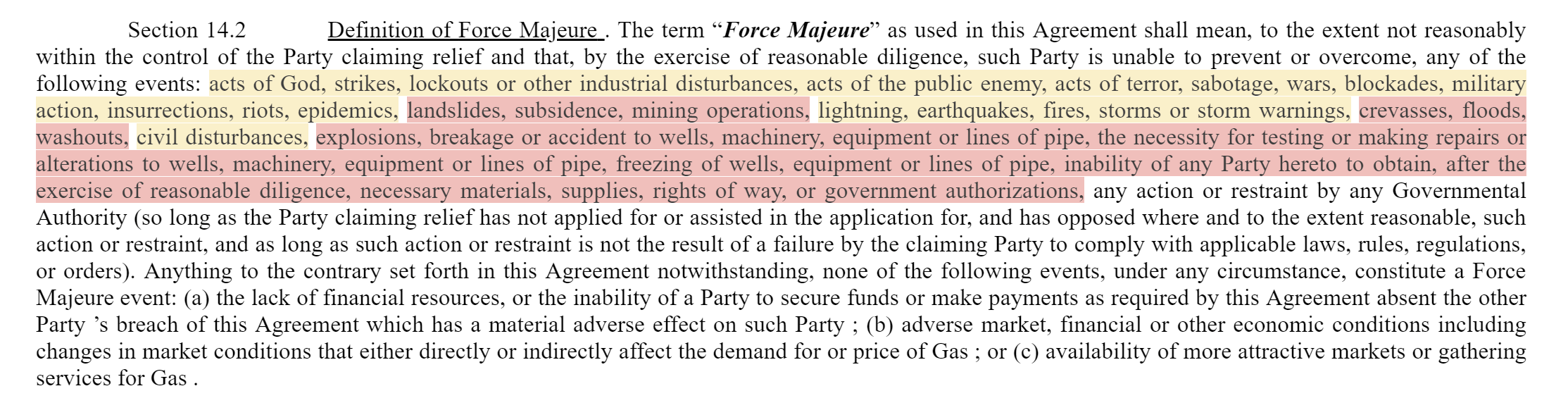

Here’s the definition of force majeure from an oil-and-gas contract:

I’ve highlighted in yellow those elements that seem to address the all-the-bad-things urge, and I’ve highlighted in red—crevasses!—those that seem to relate to the work being performed under the contract.

It’s not a good idea to mix those two elements. You should be able to address with much greater specificity the risks that pertain to work under the contract. Do so separately.

Foreseeability Doesn’t Make Sense

As mentioned above, foreseeability features in caselaw on force majeure. That doesn’t make sense. Here’s what I say in my 2018 blog post:

Everything can seem foreseeable if you have a broad enough frame of reference. Is it foreseeable that this train is going to crash? Perhaps not, but it is foreseeable that at some point somewhere a train will crash, and it’s just a matter of odds whether it’s this one. And is a hurricane foreseeable or unforeseeable? How you answer depends on your perspective. I’d rather not have that kind of fight, so bring on the half-page definition of Force Majeure Event.

In other words, eliminate foreseeability as an issue: in your force majeure provision, use the phrase whether or not foreseeable. Instead, focus on preparedness: make it a condition to invoking force majeure that the party in question’s inability to perform isn’t due to its failure to (1) take reasonable measures to protect itself or (2) develop and maintain a reasonable contingency plan.

What Are the Implications If a Force Majeure Provision Is Triggered?

If an event or circumstance triggers a force majeure provision, the nonperforming party is excused from not performing. But things can get murky. For example, what if a group booked a conference at a hotel and paid a deposit, then cancelled because of COVID-19? Arguably both the group and the hotel are excused from performing. But what happens to the deposit? Unless the contract specifies, there’s no clear answer. (The second extract above is specific—the hotel has to refund the deposit.)

The more specific you are, the better.

Whether to Include a Force Majeure Provision

Should you include a force majeure provision in a draft? Here’s what my 2018 post says:

Force majeure provisions originated in contracts for infrastructure projects, but by process of osmosis they’ve migrated pretty much everywhere. (For example, for a consulting client I’m working on a contract for financial services; the template that is my starting point contains a force majeure provision.) It’s hard to object on principle to this expanded use of force majeure: an earthquake that disrupts tunnel building can also mess with financial transactions. But you could decide to forego entirely the reallocation of risk inherent in force majeure provisions.

At issue is whether the parties are committing enough to the relationship that it would be fair to revisit the risk allocation. There’s no right answer—it’s a function of bargaining power and the nature of the risk.

What If There’s No Force Majeure Provision?

If a contract doesn’t contain a force majeure provision, a party could invoke the common-law defense of commercial impracticability. Negotiating and Drafting Contract Boilerplate 323 (Tina L. Stark ed. 2003) says, “While modern courts readily entertain the impracticability defense, they apply the defense inconsistently.” No surprise—they’re wrestling with vagueness.

And the defense of impracticability has been incorporated in § 2-615 of the Uniform Commercial Code for contracts involving the sale of goods.

Whatever the merits of the defense of commercial impracticability, a force majeure provision has the benefit of evidencing, at a minimum, that the parties recognize that it might at some point be appropriate to suspend arrangements provided for in the contract.

What Matters for Purposes of Contracts You Have Yet to Sign

You’re drafting or negotiating contracts. Should you include a force majeure provision? If so, what should it look like? Some suggestions:

- Based on what’s at stake in the deal and your appetite for risk, decide whether to include a force majeure provision.

- Remember that even without a force majeure provision, the remedy of commercial impracticality might be available.

- If you include a force majeure provision, have it apply just to the all-the-bad-things risk. Keep separate risks that pertain directly to the work being performed.

- Do your best to address explicitly the consequences if the force majeure provisions is triggered.

- Don’t include a parade of horribles.

- Consider including carveouts. In particularly, carve out the current pandemic!

- As an alternative to making foreseeability an issue, impose conditions on the nonperforming party’s invoking force majeure.

A resource you might find helpful is my force majeure provision, which is in this 2013 blog post.

What Matters for Purposes of Contracts You’ve Already Signed

We’re in the time of coronavirus, and you company is party to a whole bunch of contracts. If your company is under pressure, or your counterparties are under pressure, it might be prudent for you to assess how force majeure plays out in your existing contracts.

But before you root around, remember these factors, each of which I discuss in this post:

- A contract might use an alternative term of art or defined term to express the concept of force majeure.

- The concept of force majeure might be expressed without a label—you have to be prepared to look for the underlying meaning.

- Force majeure won’t always be where you expect to find it in a contract.

- Recognize the limitations of the parade of horribles.

- Recognize the limitations of foreseeability.

- In the absence of a force majeure provision, a remedy under the Uniform Commercial Code or the common-law remedy of commercial impracticability might be available.

Whether the coronavirus epidemic would trigger a force majeure provision in a contract would depend on the circumstances and the contract language. That’s beyond the scope of this post. This article in the National Law Journal by lawyers from McDermott Will & Emery would give you an idea of the inquiry involved, but take into account the issues discussed in this post. And I can see some topics that might come into play, whether or not they make sense:

- Is COVID-19 an act of God? A natural disaster? Well, human agency has certainly been involved: Eating bats, perhaps. Ignoring advice to stay home. Feckless government.

- It might matter why and when a party stopped performing. Out of prudence? Because of a government order?

- Protective measures taken by a party might be of limited significance: we’re all responsible for containing the spread of a pandemic.

How would you look for force majeure in your contracts? If you have more than a handful, it would make sense to automate the task. With all the AI-and-contracts companies out there, you doubtless have different services targeting force majeure to choose from, but the one option I know of is that offered by LegalSifter. It’s described here.

LegalSifter’s service incorporates my expertise. Other companies offering this kind of service rely on … who knows. If I can’t identify whose expertise is being used, I can’t trust it. If you’d like to know more about how LegalSifter might be able to help you, click here to send LegalSifter an email.

A tour de force majeure!

Nice post, Ken! I’m glad they baited you into it.

I hadn’t seen your post on renaming “force majeure”. iIve mostly settled on “valid excuses” in my plainer forms.

Once I did have opposing counsel also paste in their boilerplate force majeure without noticing. But just once, and the other edits in the turn didn’t betray a lot of careful attention. Likely short on time.

I will look forward to referencing your “parade of horribles” in some other contexts. The analysis comes up a lot when others see abbreviated warranty disclaimers and damage exclusions. Traditional drafters are really just more comfortable trying to list ’em all, while at the same time fairly ready to admit that the hand-me-down list fills the page precisely because we’ve repeated the cycle of lawyer writes list, case pulls at heartstrings, court decides list item is missing, lawyers add item to list.

Thanks, Ken! Good stuff as always.

Ken, I’m having a hard time figuring out how the below phrase from your FM clause would be applied in practice. I can see how it could work if clear steps were actually taken, but I can’t see how it would work if an event was unforeseeable or if there was an unavailability of steps:

“failure to (A) take reasonable measures to protect itself against events or circumstances of the same type as that Force Majeure Event or (B) develop and maintain a reasonable contingency plan”

For example, what would court find was a reasonable measure or contingency plan for a manufacturer that was to produce widgets on a particular schedule, but couldn’t meet the deadline due to government limits on people present at the workplace? That question is sort of rhetorical, so you don’t have to give examples…I’m just thinking that if a client asked me that question, I wouldn’t have a helpful answer.

A lot of business interruption insurance policies are worded in a way that coverage isn’t triggered by COVID-19, so I don’t think business interruption insurance would be seen as a reasonable measure.

With the above clause in effect, would a prudent manufacturer have to implement contingency plans for every possible parade of horribles? What if there is no good alternative plan (e.g. only possible manufacturing plant due to specialized equipment)? Does the non-existence of a good alternative mean that all reasonable steps were taken?

I think the reality is that most businesses have no contingency plan—hell, the government doesn’t even appear to have one!

I’ve started adding the following to my FM clauses with vendors:

1. a requirement that the party claiming excuse provide prompt notice so that FM doesn’t become an after-the-fact catchall for a failure to perform

2. a right to terminate if the delay extends beyond X days, in order to provide motivation to resume performance;

3. the obligation to refund any prepaid fees if the agreement is terminated due to 2, above.

Hi. Sorry for the late reply. I think your 1 and 2 are consisten with my FM language.

Appreciate all the practical tips. Awesomely thorough as always.