In this March 2022 post, I examined an article by Eric Martinez, Frank Mollica, and Edward Gibson about their study showing that contracts are poorly written. I said that this article tells us nothing we don’t already know.

The same authors are now back with another article, this one entitled Even Lawyers Do Not Like Legalese (here), published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. I learned of it because it was the topic of this article in The Economist (behind a paywall). The new PNAS article is more problematic than their previous article—because of flaws in the design of the study, the new article is misleading. (All references to an article in the following analysis are to the PNAS article.)

The New Article

Here’s the “Significance” paragraph from the new article:

Why do lawyers write in such a convoluted manner? Across two preregistered experiments, we find that lawyers a) like laypeople, were less able to understand and recall “legalese” contracts than content of equivalent meaning drafted in a simplified register; and b) rated simplified contracts as equally enforceable as legalese contracts, and rated simplified contracts as preferable to legalese contracts on several important dimensions. Contrary to previous speculation, these results suggest that lawyers who write in a convoluted manner do so as a matter of convenience and tradition as opposed to an outright preference and that simplifying legal documents would be beneficial for lawyers and nonlawyers alike.

The first experiment tested what the authors call the “curse of knowledge hypothesis”—the idea that lawyers are so immersed in legalese that it’s natural to them and they don’t realize the challenges it poses to others. The second experiment tested the “copy-and-paste hypothesis,” the “in-group signaling hypothesis,” the “it’s just business hypothesis,” and the “complexity of information hypothesis.” Each experiment presented lawyers with a contract extract representative of legalese and a simpler version of that extract and then posed questions relating to the differences between the two versions.

The Choice of Hypotheses Is Confusing

In effect, these experiments explore two questions. First, do lawyers acknowledge that legalese could be written more clearly? And second, do lawyers consider that the clearer alternative to legalese is acceptable? But the authors muddy the waters by building the study around their five hypotheses. Instead of testing facts, their five hypotheses attempt to test something murkier—explanations for those facts.

Regarding experiment 1, “the curse of knowledge” refers to a cognitive bias that occurs when an individual communicating with others assumes they have a similar background and depth of knowledge. But for two reasons, that’s an unhelpful concept on which to base experiment 1. First, the curse of knowledge doesn’t suggest that a speaker who has been so cursed thinks that their way of communicating is the only way of communicating, or is the clearest way of communicating. Instead, it suggests a choice that misreads the audience. And second, there’s another possible reason why some lawyers might think that legalese is clear: they might never have considered that one could write contract prose differently. In fact, experiment 1 itself might be what causes a lawyer to consider, for the first time, an alternative to legalese.

Regarding experiment 2, the four hypotheses are confusing in three respects. First, the experiment aims to validate the first hypothesis and refute the other three—an awkward mix. Second, I suggest that the “in-group signaling hypothesis” and the “it’s just business hypothesis” are functionally indistinguishable. And third, the latter three hypotheses don’t exhaust the possible reasons for sticking with legalese; consider the various sources of inertia Casey Flaherty lists in this 2018 post.

So the study would have been clearer if instead of basing the hypotheses on explanations it had tested these two hypotheses:

- Lawyers acknowledge that legalese could be written more clearly.

- Lawyers consider that a clearer alternative to legalese is acceptable.

Discussion of explanations would have better been left to the analysis section.

Contrary to the Design of Experiment 2, Clarity Doesn’t Affect Enforceability

In experiment 2, the subjects were asked to rate, among other things, the enforceability of the contract extracts. But if you assume that each “legalese” extract contains a provision that doesn’t raise enforceability issues, it follows that the ostensibly clearer “simple” version expresses the same meaning and so wouldn’t raise enforceability issues either. So that element of experiment 2 isn’t legitimately a survey. Instead, it’s like asking people whether the earth is flat or round.

The Experiment Extracts Aren’t As Advertised

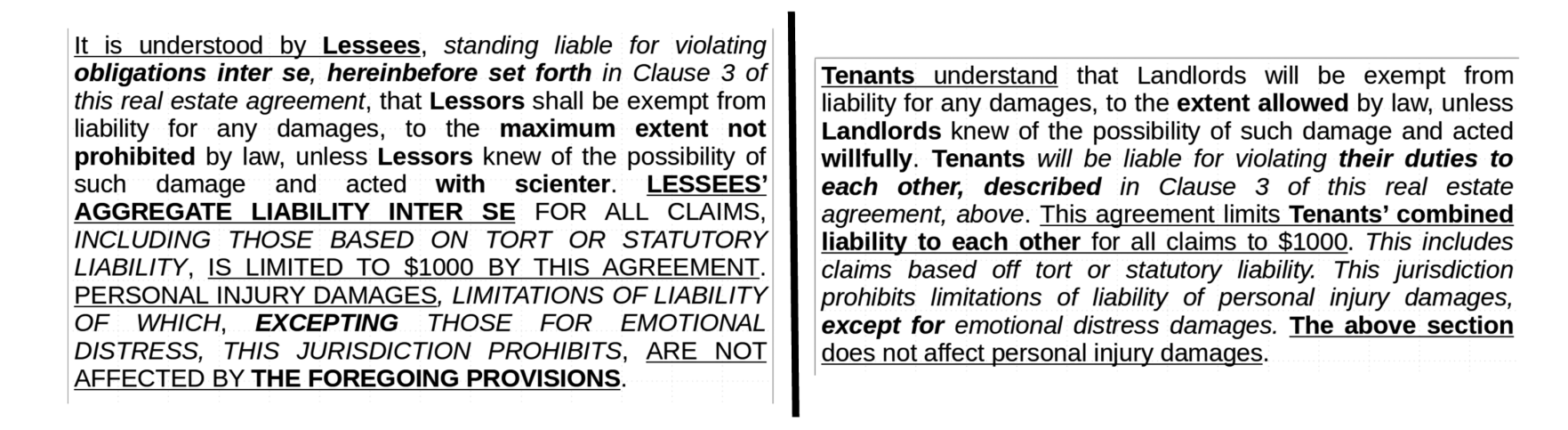

The screenshot below is from the article. It shows one of the pairs of “legalese” and “simple” extracts used in the study. The study participants weren’t shown the two extracts side by side. Instead, some were given the legalese version of the passage and others were given the simple version.

I wouldn’t use for these extracts the labels “legalese” and “simple.” Instead, “batshit legalese” and “legalese,” respectively, would be more accurate.

For one thing, the “legalese” extract features three marginal traditionalist usages, namely inter se, scienter, and hereinbefore. The word scienter occurred in only 13 contracts filed on the SEC’s EDGAR system in the 60 days before the day I ran the search (a couple of weeks ago). (By way of random comparison, the word negligence occurred in 3,742 contracts.) The phrase inter se occurred in only 21 contracts. (I confess to not having encountered inter se previously!) And the word hereinbefore occurred in only 201 contracts. (By way of comparison, more than 9,000 contracts filed in the same period use the word hereunder.)

As for the “simple” extract, it’s utterly different from how I’d say what it says. To pick just one example, I wouldn’t use the word willfully. (See this 2007 blog post about willful.)

The net effect is that these extracts make it easy for a lawyer wedded to traditional contract language to reject the “legalese” version or feel at home with the “simple” version (depending on which they were exposed to). As such, the extracts might have skewed the results of the study.

The Experiment Extracts Underplay the Impact of Legalese

Based only on my review of the extracts in the image above, it might be that the extracts in the study skirt what is the most pernicious result of legalese—confusion. Yes, legalese is certainly old-fashioned and wordy, so the reader wastes time disentangling what’s being said. But beyond that, plenty of phrases that are the stock-in-trade trade of legalese (time of the essence, efforts provisions, indemnify and hold harmless, consequential damages … I could go on and on) give rise to fights. Extracts that don’t include such phrases can’t be said to be fully representative of legalese.

Regarding how that relates to the study, omitting such phrases might make it easier to lawyers to disdain the “legalese” version: because the conventional wisdom attributes substantive implications to such phrases, it’s safe to say that some lawyers would be reluctant to give them up. But it wouldn’t have been possible to test that in this study, because it would result in the “legalese” and “simple” versions arguably expressing different meanings rather than just levels of clarity.

The Problem with Lumping All the Experiment Subjects Together

The study results show what proportion of the experiment subjects responded in a given way to various questions. As such, the study isn’t illustrative of the views of individual lawyers, just as testing wastewater for COVID-19 tells us nothing about the status of individuals. Nevertheless, the “Significance” paragraph speaks in terms of lawyers collectively, as if they act in lockstep.

That’s unrealistic, and it doesn’t match my experience. I’ve found that the appetite for legalese varies among lawyers—I’ve encountered plenty of staunch traditionalists.

The awkward reality is that the legalese that’s endlessly copy-and-pasted didn’t all originate in the sixteenth century. Instead, new legalese is constantly being created anew and fed into the copy-and-paste machine by lawyers who are opting for legalese, clearer alternatives be damned.

So in this way, too, this article paints too rosy a picture of the willingness of lawyers to forgo legalese.

A Production Error

I noticed a production error in the article. In the screenshot below, the highlighted portion repeats the preceding four sentences. (Note how the word “gobbledygook” is the last word before the highlighted extract and is the last word of the highlighted extract.) Because this glitch might confuse readers, I mention it here.

My Take

For purposes of drafting contracts, we are all, to some extent, cranking the handle of the copy-and-paste machine. A lifetime of anecdotal evidence suggests to me that we react differently. Due to a legalistic mindset, cognitive dissonance, or some other mechanism, some find ways to rationalize the dysfunction—ours is the best of all possible worlds! Others are aware of the dysfunction but don’t have the time, authority, means, or expertise to do anything about it. And because they’re inexperienced, or jaded, or lacking in semantic acuity, still others are oblivious—it’s all a blur.

Given its shortcomings, the new study doesn’t add to my understanding of this.

(I sent the lead author, Eric Martinez, a draft of this post. In his initial reply, he said that a lot of it looked “pretty reasonable” but that he had some comments. I ended up giving him two weeks to run his comments by his co-authors, but Eric and his co-authors ultimately decided not to offer any comments. If anyone else has comments, I’d be pleased to hear them.)

The Economist is a serious newspaper as well as being author of its apparently best seling Style Guide. Consequently, it takes a serious, experienced and knowledgable person to tackle that publication and that is you, Ken Adams. Thank for your June 19, 2023 article.

As a retired country solicitor, I have lost my firghting spirit. I appreciate the time and effort it took you to write your coherent rebuttal. Most appreciated.

Dirk Sigalet, KC

2905 29th Street,

Vernon , BC V1T 4T8 Camada 250 306 2418

Hi Dirk. Thank you for the kind words. The article describing the study wasn’t published in The Economist, it was described in a separate article in The Economist. So I revised my post to name the journal in which the original article was published, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and I’ve change, with respect to The Economist, “featured in” to “the topic of”. I apologize for any confusion!

The title of the study “Even Lawyers Don’t Like Legalese” is misleading. It suggests that a typical attorney won’t like the current state of contract drafting and would prefer contracts drafted without legalese. But instead of defining “legalese” as the amount of specialized legal language employed in a typical contract, the study authors are use a distorted ad-hoc definition.

Here is how the authors define legalese (by example, because the authors do not otherwise define it):

**The first set, “legalese” contracts, were written in a style containing linguistic features that have been shown to be disproportionately common in legal texts relative to non-legal texts, and which have also been shown to inhibit recall and comprehension of legal content relative to contracts without these features.** (starting at line 137).

Translation: prior studies showed that certain linguistic features inhibit recall and comprehension so we put a lot of them in the text we’re arbitrarily defining “legalese.”

I find it baffling that the authors of a study published in PNAS neither define nor quantify the amount of legalese in the extract. The only justification I can think of is that the authors are building from prior work and want their work to mesh with prior studies. But if that’s the case, it’s compounding an existing problem–the continuing lack of a useful definition of legalese in the budding literature.

Here is what the authors say about the “simple” extract:

**The second set, “plain-English” contracts, were of equivalent meaning drafted without these difficult-to process features.** (starting at 142).

Translation: we took out the weird stuff and left the ordinary legalese.

The “legalese”extract is not legalese. It is a concoction of things that other studies have (evidently) proven are hard to read, cranked up to 11. If I had read the “legalese” extract without context, I wouldn’t even think a lawyer wrote it—I’d think someone was playing a prank.

Neither is the “plain-English” extract what it purports to be. It not “plain-English”; it’s still legalese (in the conventional sense, not the “up to 11” used in the study), albeit with less specialized legal langauge than what you’d find in a typical contract on EDGAR.

So the “legalese” extract is legal gobbledegook and the “plain-English” extract is “legalese.” This makes the title of the study inherently misleading because the actual comparison in the study is between nonsense and actual legalese.

Here’s title that the study actually earned: “Even Lawyers Don’t Like Gobbledegook.”

The false comparison between legal gibberish and more conventional legalese throws all of the conclusions reached in the study into doubt because the study says nothing about the comparison between traditional legalese and styles of drafting that eschew legalese in favor of less specialized language.

On a side note, the authors also discuss “simplifying” contracts, but that’s false hope. Contracts can certainly be redrafted better, but legal documents are irreducibly complex. If you remove too much essential complexity, the contract is no longer fit for use. So specialized legal language in contracts can be toned down or removed, but contracts cannot necessarily be simplified.

Unironically, the conclusion that the study authors reach is probably correct. Had the authors set up the study properly (comparing extracts from EDGAR to MSCD-compliant redrafting of those extracts), the study authors would likely have found that most people (including lay people and lawyers, but excluding some traditionalist stalwarts) would prefer MSCD-compliant contracts to the traditional legalese that is rife on EDGAR. But the study authors didn’t earn that conclusion.

An opportunity lost.

“Batshit legalese” – saving this gem for future use!!

Echoing what others have said, the “legalese” sample reads like a caricature. It reminds me of a brief written by a pro se prisoner. The “plain language” reads like the workaday legalese contracts the routinely crosses my desk.

After decades of being scolded about using legalese, I’m less certain now than ever about what “legalese” even means. In the article here, it seems to mean the unnecessary use of latinate terms. This can be irritating, but I have yet to meet the person who can’t noodle out the meaning of “hereinbefore.” And if you can’t, you probably shouldn’t be reviewing contracts. My bigger issue is the awkward sentence structure with all the embedded clauses. To me, that is the real culprit of the poor writing on display in the article. You could take all the Latin out, and I still couldn’t follow it.

Finally, anybody involved in writing that “Significant Paragraph” has no standing to criticize anybody else’s clumsy writing.

Brian: The lack of a definition of “legalese” is–in my mind–the biggest flaw in the PNAS study. The author’s failure explicitly define legalese in the study leaves us with a definition that is circumscribed by the “Significant Paragraph.” But that paragraph, characterized by

“center-embedded clauses” and excessive use of Latinisms, is woefully inadequate to describe what most people mean when they bemoan “legalese.”

There a dozens, hundreds even (based on the MSCD) of legal writing dysfunctions that contribute to the comprehension problems that people perceive as legalese. This suggests that “legalese” ought to be defined by its measurable effect on the reader and not by specific instances of the dysfunction.

For example, we might measure how long it takes a person to read a particular legal text, then administer a reading comprehension test. Then compare those results to control texts. Legalese could be used to label a legal text that causes certain measurable reductions in reading speed and comprehension.