[Updated 1:40 a.m. 21 February 2020 to expand the analysis to address additional text in the screenshot Warren tweeted.]

On 19 February, the Nation published this article by Ken Klippenstein about the Bloomberg campaign’s confidentiality agreement. The article contained this link to a copy of the confidentiality agreement. All I have to say about it is what I said on Twitter:

This NDA exhibits the standard dysfunction of traditional contract drafting, in terms of what it says, how it says it, and its layout. I'm shocked! Not. https://t.co/hO4bht3qyl

— Ken Adams (@AdamsDrafting) February 20, 2020

I have no interest in critiquing this sort of generic stuff. Life’s too short.

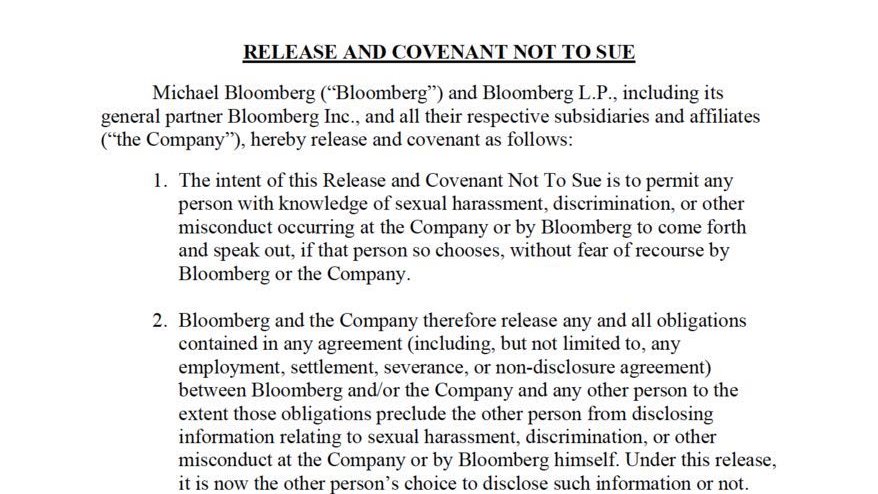

But this evening, during a CNN “town hall,” Elizabeth Warren brandished a “release and covenant not to sue” that she herself had written, seeing, as she says, that she used to teach contract law. The idea is that if Bloomberg signs it, it would have the effect of allowing anyone who had signed a confidentiality with Bloomberg or his campaign to speak freely. She read out the relevant language. This tweet contains the relevant clip:

Upon walking on stage at #CNNTownHall, @ewarren ups pressure on Bloomberg, provides a sample contract for him to sign to release all the women & men held under NDAs.

She pulls no punches & is the fighter we need as prez. Donate to make that a reality: https://t.co/u2s3r9Gth8 pic.twitter.com/9bAGlpfqt8

— BoldProgressives.org (@BoldProgressive) February 21, 2020

She also posted a screenshot on Twitter:

Seeing as I analyze contract language for a living (go here for more about me), I thought would be interesting to look at Warren’s proposed language, with the real draw being that she apparently wrote it herself. Here are my thoughts, such as they are:

- I’d use the title RELEASE. The word covenant is old-fashioned and redolent of the Old Testament and Raiders of the Lost Ark. If you want to keep the “not to sue” part, I’d use the word undertaking.

- Why bold the title? Why underline it? That’s overkill: all caps is enough.

- It’s a bad idea to include subsidiaries and affiliates in the definition of the defined term for the company. Because the subsidiaries and affiliates aren’t party to the release and so wouldn’t be bound by any of its provisions, including them in the definition just confuses matters. See my book A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting (MSCD) ¶¶ 2.54, 2.95 (4th ed. 2017).

- In the defined-term parenthetical creating the defined term the Company, putting the definite article the within the quotation marks is unorthodox.

- It’s awkward to have two instances of language of performance using the verb release (the first one in the opening paragraph, the second in paragraph No. 2). To fix that, I’d turn paragraph No. 1 into a recital saying what Bloomberg and the company want the release to accomplish, and I’d have the next paragraph begin “Bloomberg and the Company therefore release ….”

- In the reference in paragraph No. 1 to “this Release and Covenant Not to Sue,” the initial capitals are unnecessary. See MSCD ¶ 2.20. In paragraph No. 2, it’s referred to more sensibly as “this release.”

- The wording of paragraph No. 1 (“come forth and speak out … without fear of recourse” is awkwardly legalistic).

- In paragraph No. 2, the phrase any and all is legalistic; just say all.

- One doesn’t release obligations; one releases people from obligations.

- In the phrase including, but not limited to, the but not limited to part is redundant, for reasons explained in this 2017 article. More to the point, in this context including examples serves no purpose, because “any agreement” means exactly that, so necessarily the stated kinds of contracts fall within the class, even without saying so.

- Using and/or is awkward. I’d say “between one or both of Bloomberg and the Company.”

- I’d use prohibit instead of preclude. People aren’t precluded from speaking out, but doing so might result in a claim against them.

- The word himself is unnecessary.

- I’d revise the final sentence to eliminate the word now—it inappropriately suggests that the release speaks at one moment in time. I might say something like from the signing of this release.

So there’s room for improvement, which isn’t surprising: teaching contract law has little to do with effective contract drafting. But taking into account that traditional contract drafting is profoundly dysfunctional, this draft is OK. To have addressed the points I make above, it would have had to have been written by a contract-drafting specialist, and there aren’t many of us. And it looks really good compared with the dumpster fire that is Trump’s contract with Stormy Daniels (go here for my analysis of that).

Can you think of any substantive issues raised by this proposed language? I can think of two. First, given that I’d want the defined term the Company to refer just to Bloomberg L.P., I’d want to have the release also signed by any other Bloomberg entities that signed contracts prohibiting disclosure, and I’d want to include a statement of fact that no other Bloomberg entities signed any such contracts. And I’d say that all counterparties to contracts falling within the scope of the release are third-party beneficiaries to the release.

Assuming Sen Warren doesn’t just tell you to “go forth and multiply”, she might argue that there is an element of political rhetoric in her document.

On substantive issues, would there be a need for consideration? Under English law I would draft the document as a deed to sidestep this issue.

I think the fixes I suggest wouldn’t undercut, and might enhance, any non- legal message.

Regarding consideration, have a look at my exchange on Twitter with Art Markham. I haven’t researched the law.

Laughed out loud when reading #4, that’s pure gold!

Regarding the “covenant not to sue” … I’ve been studying releases and waivers lately, and some commentators in the field say the “covenant not to sue” is almost always included with the waiver. Some courts see no difference, while others recognize and give independent meaning to the phrase (for example, without looking at the cases myself, I’m told to review a 2004 California case in Bossi v. Sierra Nevada Recreation Corporation and a 1993 Nebraska case in McCurry v. School Dist. of Valley).

In summary, waive means to “give up,” and covenant not to sue means to “not file suit.”

But if I understand your analysis, you’re not saying you would get rid of the “covenant not to sue” entirely, you would just use different language. If that’s what you’re saying, is the phrase “undertake” as in The Undertaker, or even the person that prepares a dead body, a great alternative? Is it more common in everyday parlance?

Ultimately, I might prefer to keep “covenant,” while agreeing it’s an old-fashioned word, simply to grab on to that independent meaning. To get the court clerks and everyone else looking in the right places for case law so they agree this document means not only that the claim is gone and waived, but that there is a BREACH of the covenant not to sue and DAMAGES if that claim is ever asserted in a suit.

Interested in your thoughts.

I’ve nibbled around this issue in the past: thanks for the reminder. My proposed changes are of the how-you-say-it variety, so I wasn’t inclined to dig very deep. But I’ll look more closely at covenants not to sue versus waivers. At the moment, distinguishing between them strikes be as legalistic nonsense.

Bloomberg L.P. can only act through its partners, so the language directing the entity and not the partners is not ideal.

An L.P. is not a company, so defining it as the “Company” is bad form. I’d suggest “Bloomberg Entities” or something like that. Let someone with knowledge of the structure figure out what goes on the list–it’s got to be huge.

Michael Bloomberg, as an individual human, does not have any subsidiaries. “Their respective affiliates and subsidiaries” needs to go.

This is a piece of paper. It does not possess intent. People do, though. “Bloomberg and the Bloomberg Entities intend to permit…”

Don’t release signatories from “all obligations contained in the agreement” just release them from the agreement. (That would in turn make all the language about releasing “to the extent” unnecessary.)

She could just say “Bloomberg and the Bloomberg Entities hereby release all parties from any Non Disclosure Agreement [defined term] executed before the date of this Release.” End of Release.

Great! Thank you. I’ll look into the partnership-as-party issue.

Regarding your subsidiaries point, I think the intention was that “all their respective subsidiaries and affiliates” modifies just Bloomberg L.P. and Bloomberg Inc. But in any event, it’s ambiguous. But more to the point, I propose eliminating that stuff, so it wouldn’t be an issue.

I had in mind redoing paragraph No. 1 entirely as part of making it a recital.

I’m not sure it’s usual to refer to releasing people from contracts. Termination might make more sense, but I don’t know what those contracts provide in that regard. But more generally, I assumed that there might be other aspects of the contracts that the Bloomberg parties might legitimately want to keep in effect.

To me, it is unclear what will happen with any benefit the other party gained from whatever settlement agreement they signed with the original confidentiality obligations. If they lose their settlement money, then there’s not much incentive for them to come forward. Maybe that’s addressed elsewhere in the agreement.