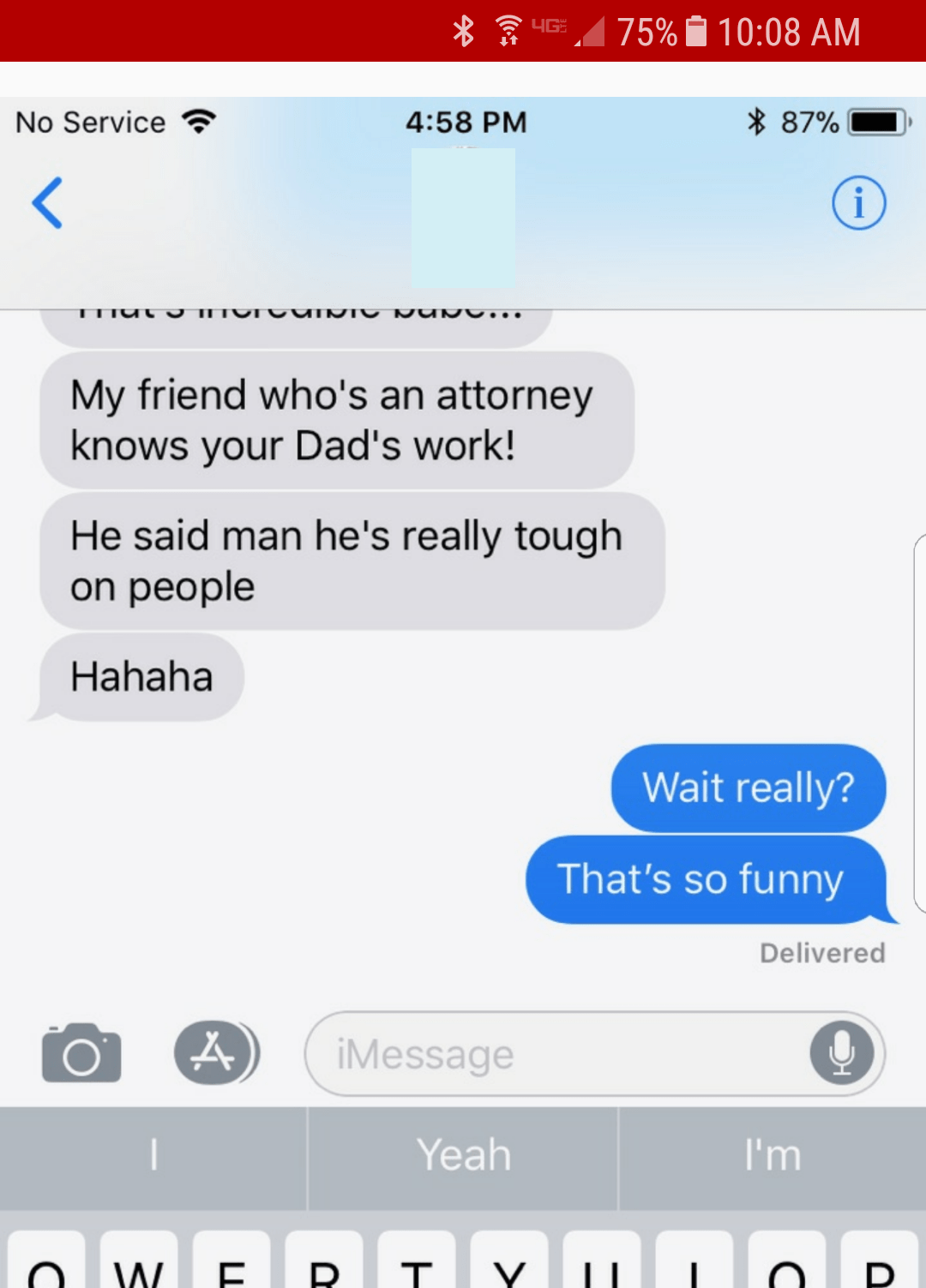

Above is a screenshot my daughter sent me a few days ago, showing texts she exchanged with a friend. “Hahaha” indeed.

I thought of it on reading Casey Flaherty’s post touching on my work (here). Casey accurately summarizes my, uh, lack of restraint.

I know some people wonder why I’m so in-your-face. A commentator on litigation writing once earnestly advised me to be more easygoing. “Don’t tell people they’re wrong! Instead say, ‘That’s great, but have you considered doing it this way instead?'”

Two factors underlie my approach.

First, contract language is different. It’s more limited and stylized than litigation writing, and more hinges on nuances of wording. If you’re inartful in how you word a sentence in a brief, any adverse consequences are likely to be modest. By contrast, an awkward choice in contract language and the result might just blow the deal. Or lead to years of litigation. Or both. So pussyfooting around dysfunction in contract language does no one any favors.

And second, if you want to effect change in a field as precedent-driven as contract drafting, it does no good to murmur deferentially in someone’s ear: you’ll be ignored. That’s why I tout my wares in the marketplace of ideas from atop the biggest soapbox I can find, and why I speak as plainly as I can. I have yet to encounter someone who has said, “We would have hired you to give us a seminar or rewrite our templates, but you’re too darn abrasive!” And if someone actually feels that way, they’re fooling themselves: if they’re distressed by my candor, they’d likely fall into a dead faint when faced with the messy change required to retool their contracts.

The nature of my plain-speaking depends on what provokes it. Usually when I critique a contract drafted by a big law firm or a global company, I’m clinical in demonstrating that the emperor is lacking some clothes. I figure that the emperor isn’t going to lose sleep over what I have to say, although a few times I’ve attempted to contact a company before publishing my analysis of one of their contracts.

If a company goes out of its way to claim that its suboptimal drafting is something to be emulated, or if a prominent commentor says something stoopid, a stiffer response is in order. And if you publicly denigrate my work, I give myself free rein to set things straight.

But in all this, I try not to be a jerk.

Ken, you definitely succeed in bringing the subject to life and injecting interest into something that bores many, but actually does matter.

Tim, I’m pleased you feel that way. I’m fortunate that I’m able to convey a little of what makes this subject so fascinating to me. That might be harder to achieve if I were constantly worrying about whether someone, somewhere, might decide that I’m being too outspoken.

“[A]n awkward choice in contract language and the result might just blow the deal. Or lead to years of litigation. Or both.”

True. A crucial word in that artfully worded passage is “might.” Not all awkward drafting choices are created equal. Some are completely benign. Life is too short, and most of my clients’ money is in too short supply, to spend time fixing benignly awkward drafting decisions in documents written by the other side in a deal. Part of the art of lawyering is discerning those drafting flaws that are likely to blow the deal, lead to years of litigation, or otherwise make a significant difference to the client from those that are likely benign.

Amen. Triage is an essential part of contract drafting: you make the choices that circumstances permit.

Ken, I think that “pussyfooting” as you put it, might hamper you and your clients more than it would help. Constantly second-guessing and treating people with kid gloves would not do anyone a service. Now, if you were providing customer service…

Many lawyers are quick to tell you they are in a profession, and presumably they still are when drafting contracts. If the drafting standard is poor, they should be called to account.

Frank feedback is not being tough, but it is sure to get a response from thin skinned lawyers.

I run a proofing workshop at two Universities. Students are genuinely surprised to learn they may lose marks when essays have typos, punctuation errors and consistency mistakes.