Hell is other people’s reviews.

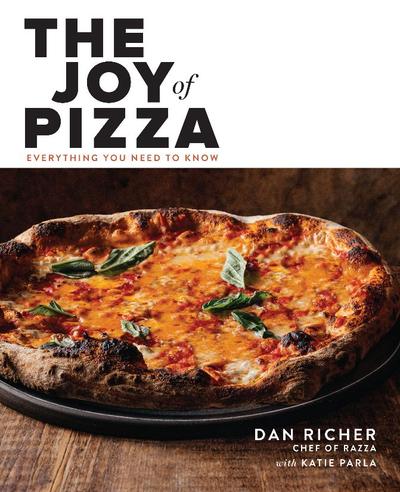

In October I bought a copy of The Joy of Pizza, by Dan Richer with Katie Parla. Richer is owner of the restaurant Razza, a noted pizza joint in Jersey City. Parla is a food writer and cookbook author based in Italy. After buying it, I looked at some reviews on Amazon. I quickly spotted two kinds of review.

The first is, It’S tOo CoMpLiCaTeD, to which I say, there are already a zillion books out there if you want to whip up mediocre pizza.

The second is, WhY dOeSn’T iT hAvE mOrE dIfFeReNt KiNdS oF rEcIpEs, to which I say, this book is about Richer’s kind of pizza, and only Richer’s kind of pizza. You want a world tour, get a different book.

I was intrigued by the book and spent some time with it, so I thought I’d try my hand at a review. The only credentials I have to offer are that I’ve devoted a long time to learning, too slowly, how to make decent pizza.

Let’s get one thing out of the way. I give it four, um, hearts out of five: ♥♥♥♥ (Wordpress symbols don’t include stars.)

Production Values

It’s a handsome, well-organized book, with beautiful photographs.

The Polemic

Richer’s pizza could be described as neo-Neapolitan, as distinct from Neapolitan style and New York-style (or New Haven-style, depending on your tribal allegiance). Neapolitan pizza is a one-person pizza featuring a simple tomato sauce, fresh mozzarella, olive oil, and perhaps a dusting of parmesan. It’s baked in a blazingly hot wood-fired oven for 60 to 90 seconds. It’s soft—you eat it with a knife and fork. New York-style is bigger, it uses a higher-protein flour, and usually low-moisture mozzarella is involved. It’s baked at a lower temperature (perhaps in a coal-fired oven), and it’s chewier, with none of that knife-and-fork nonsense.

Richer stakes out the middle ground, offering an individual pizza that’s sturdier and crunchier than Neapolitan, with a crust that’s more fully caramelized and so more flavorful. But it’s also lighter and perhaps more sophisticated (my word, not Richer’s) than New York-style pizza.

My heart belongs to New Haven-style, due to visits to the original Pepe’s. (This photo is of one of my Pepe’s-inspired pizzas.) But thanks to the opportunities afforded by my Ooni pizza oven (blog post to come), I’ve been experimenting with Neapolitan pizza, but I’ve been dissatisfied. I was ready for Richer’s take.

On page 107, he refers to “the ‘leopard spots’ on the rim that are so popular in wood fired pizza making but are in fact a flaw.” Preach! Enough with the leopard-spotting fetish. And I’m not sure buffalo mozzarella features in any of his recipes. He suggests that if you use it, you put it on pizza after it comes out of the oven. That too I was ready to hear. Although I have a supply buffalo mozzarella readily available (at Whole Foods), I’ve never understood the appeal. Compared with cow’s-milk mozzarella, which melts readily, I find that buffalo mozzarella ends up looking congealed.

The Intensity

A feature of the book is “rubrics” (questionnaires) for evaluating pizzas and raw ingredients. They’re helpful as a consciousness-raising exercise, but I didn’t pay much attention to them. If you own a restaurant, it makes sense to make your process industrial. Me, I’m doing a couple of pizzas once a week or once a month, so I don’t bother with the rubrics.

On the other hand, going forward I’ll determine what temperature my water should be by taking into account the air temperature and the temperature of the flour, as Richer recommends.

The Nitty-Gritty

I’ve made four batches of Richer’s “everyday dough.” The recipe essentially applies bread-making techniques to pizza. It was quite revealing. After you mix flour, yeast, and water and then, after an interval, salt, you knead the dough. But you don’t knead it the regular way. Instead, you use “the Rubaud method”—with the dough in a bowl, you work your way around the outside of the dough, lifting an edge with a cupped fingers, then letting it fall back. You do that for 5 to 7 minutes. Initially, I thought, why am I doing this to this ragged mass of dough that doesn’t look like the pictures in the book? Then after 5 minutes, I observed that, hey, the dough ain’t ragged anymore!

Add to that Richer’s stretch-and-fold technique and the result was a dough that was lively and well-structured, compared with my various attempts at making Neapolitan dough, Caputo “00” flour and all.

But in the course of doing my four batches of dough, I decided to do three things differently than Richer recommends.

Hydration

First, Richer’s everyday dough is a high-hydration dough, with 76% water. He recommends you reduce it to 68% hydration for high-temperature ovens, like my Ooni. I tried that once, but it made the dough noticeably stiffer, to the extent that it was tough to apply to the dough Richer’s stretch-and-fold technique. I wonder whether in researching the book he actually worked with 68% hydration dough. But as it was, that turned into a moot point: I found that pizzas made with 76% hydration dough were lighter and crisper than their 68% hydration counterparts. The Ooni is sufficiently versatile that I was able to avoid the burning that Richer warns about. I don’t expect to make the 68% hydration version of the dough again.

Second Fermentation

Second, with Richer’s recipe, the dough does a bulk ferment in the fridge for a day, after which you divide the dough into rounds and put it back in the fridge for at least another 12 hours. I did it that way with three of the four batches, but I found that after a day in the fridge, the structure the dough had acquired interfered with creating even dough balls. So I switched to the approach used by Ken Forkish in The Elements of Pizza: he uses a short initial bulk fermentation and a long secondary fermentation. (I’d previously done the same switch when using Joe Beddia’s book, Pizza Camp.) The dough balls ended up a bit more even, and it made the whole process simpler: I was able to mix, knead, do the initial bulk ferment, and create the dough balls over the course of 3 to 4 hours. And the dough balls were ready to go after sitting in the fridge overnight, but they were fine after a second day too.

Size of the Dough Balls

And third, the recipe for everyday dough says you should create dough balls weighing 250 grams and says they should create a 12-inch crust. That’s not what I found. Instead, I got to only 10 inches. (See the upper of the two associated photos.) In trying to get to 12 inches, I ended up putting holes in the crust. And in the resulting pizzas, the rim was as puffy as it would have been with a bigger pizza, so it occupied a bigger proportion of the surface area, leaving a relatively puny sauce-covered part. They looked a little silly.

I wasn’t surprised: in The Elements of Pizza, Forkish says that a 287 gram dough ball will give you an 11-inch crust. I don’t see how Richer and Forkish can both be right. After my first batch of Richer’s dough, I switched to making 290-gram dough balls, which did indeed yield 11-inch crusts. (See the lower of the two photos.)

I expect that others will encounter this problem. Those who are relative newcomers to pizza might end up befuddled. I don’t think it was anything I did. For one thing, the dough wasn’t cold: I gave it a couple of hours to warm up.

It’s not the first such problem I’ve encountered in a pizza recipe. Beddia’s dough recipe in Pizza Camp calls for cool water. Anyone who follows the recipe will find themselves with lifeless dough, something that Beddia acknowledged to me.

[Updated 13 September 2024: A couple of people have posted comments expressing surprise that I found it difficult to achieve a 12-inch crust with 250 gram dough balls. All I can do is chalk it up to the mysteries of pizza. That Ken Forkish’s recipe provides for 287 gram dough balls suggests I’m not out of my mind.]

The Upshot

Richer’s book helped me take the next step in my pizza education. I can now put Neapolitan pizza behind me; when I’m looking for an alternative to plying people with slices (as good as they are), I now have something interesting to offer.

I’m happy with Richer’s recipe for everyday dough, with my adjustments. I ended up making some really good pizzas—light and flavorful, with a bit of crunch to them. Below are photos of a margherita pizza (please excuse the lack of any basil), the undercarriage of that pizza, a slice of that pizza (airy rim; no floppiness), and my riff on a Beddia recipe, pizza with Swiss chard, cream, and gruyère in addition to mozzarella (it’s what I had on hand).

The bake still needs some work. I’ll have to fiddle with the Ooni settings over the course of the bake and the total time of the bake.

At some point I’ll try Richer’s sourdough recipe, but a guy can eat only so much pizza …

Did I get your second fermentation correctly: knead and put the entire batch in the fridge for a few hours, remove and create balls, then put the balls back in for 12-24 hours?

Hi Steven. Actually, the initial bulk fermentation takes place outside the fridge. Richer’s book has you put the dough in the fridge after a couple of hours of bulk fermentation and folding, and you leave it in the fridge overnight before creating the dough balls. By contrast, Forkish’s book has you create the dough balls after the intial bulk fermantation for a couple of hours outside the fridge, so the first time the dough goes in the fridge, it’s as dough balls.

I agree that 250 gram piece of dough is difficult to stretch to 12” without tearing the dough. What I’ve learned from personal experience after watching various YouTube videos, is that after stretching and topping the pizza, pizzaiolos then give a final stretch to the pizza while it’s on the peel, prior to launch. That has helped me achieve a 12” base without having to up the dough beyond 250 grams, risking a thick doughy end product, especially in my high heat Ooni Koda.

Hi Carl. That’s interesting; I’ll give it a try. But “think” and “doughy” aren’t words I’d use to describe my 290-gram pizzas!

That’s great, thin we’ll done pizzas the kind I grew up eating as the gold standard as well. Trenton Tomato Pies are the best pizzas I’ve ever had, other than DiFara’s. Never been up to New Haven but I’m aware of the lore and they def look like the best pizzas in America haha. I’ve only used type 00 flour in the Ooni so no matter how much I tinker with the heat the cornicione inevitably puffs up too much and it’ll never achieve that Trenton/New Haven crisp. I’ve started using Tony Geminani’s flour mix from Central Milling for the pitas I make for my Egyptian falafel company, and I’m loving the strong glutinous texture of the dough, but I’ve haven’t yet had a chance to make pizzas with it. Which flour do you like to use to make crispy pizzas in your Ooni?

Mr. Adams! Excellent review. Thank you for that. As it happens, I agree about the complication level here. I’m “reading” The Joy Of Pizza right now. (Audiobook, so that’s why the quotes.) I mean, come on. Calipers for measuring your pizza? Develop a relationship with a local miller? Definitely not a book for beginners. I actually wrote a book for beginners myself because there is no book I’ve found that’s simple enough for the rank amateur who just wants pizza, not projects. But I digress.

I’m puzzled about your challenge with stretching the dough to 12 inches. You let the dough ball rest for a couple of hours, which would be my first suggestion. Your cross section photo of the crumb, while it looks fantastic and open, also looks really thick for a Neapolitan-style pizza. I’m wondering about your flour. Since it seems that you’re using Caputo “00,” I wonder if that’s part of the challenge. I’ve been able to get an astonishing amount of stretch out of King Arthur AP. Sometimes you can read a newspaper through it. Since it seems you’re in Canada, have you tried Robin Hood AP? Cheers!

Hi Blaine. Regarding the size of the dough ball, my opening assumption was that I was mistaken, but I thought it compelling that Forkish uses a bigger dough ball for an 11-inch crust. At some point I’ll try letting the dough balls sit longer.

I actually used King Arthur all-purpose flour. And I’m in New York :-)

Well, Ken–

It’s clear that I’m not reading closely enough. Wouldn’t be the first time. When you mentioned Caputo, you were referring to Richer’s dough. And since your bio opens with the Canadian periodical The Lawyers Weekly calling you “the guru of contracts drafting,” well… you know. Nonetheless, the pizza looks great. And if you’re ready for an even more complicated book, try Modernist Pizza. (They admire Dan Richer’s rubric and call his pizza “astoundingly good.”) Cheers!

I plan on getting the Modernist Pizza book when I feel like indulging myself!

Great review, I know I’m late to the party but in regards to stretching, it’s usually just a matter of making sure the dough is properly proofed and ready to be opened. I get an 11-12inch pie from a 215g dough ball. But I guess your mileage may vary depending on the flour used and hydration.

Hi Julian. Thanks for your comment. Yes, I’ve become aware of this. But I’m OK with what I had to say, for three reasons.

First, I got the results I did after twice following the recipe closely.

Second, that Ken Forkish’s recipe for a comparable pizza calls for a bigger ball suggested to me I wasn’t crazy.

And third, bigger isn’t necessarily better. Recently I did a biga bread-flour dough that had essentially no spring-back, so I made a big, cracker-thin pizza. It was different; I prefer a thicker crust.

But next time I make Richer’s dough, I’ll experiment to see whether I get a different, and perhaps optimal, result.

Ken

Totally understand. Although honestly 290g seems like quite a lot of dough an 11 inch pie but at the end of the day we all have different characteristics we’re looking for in our bakes.

Good luck in your pizza journey and thanks again for providing this great review.