[Updated 3 February 2017]

On 30 January I rolled out in this post a new version of the introductory part of my severability language. That prompted me to look at the rest of it, and I realized that it didn’t work. For example, “then that provision will be modified”? Passive voice? Who’s the actor? And what category of contract language is that? So back to the drawing board.

That in turn prompted a comment from a reader to the effect that the introductory part was bizarre: “it would be consistent with the wishes of the parties”? WTF! It sounds like something said at the reading of a will.

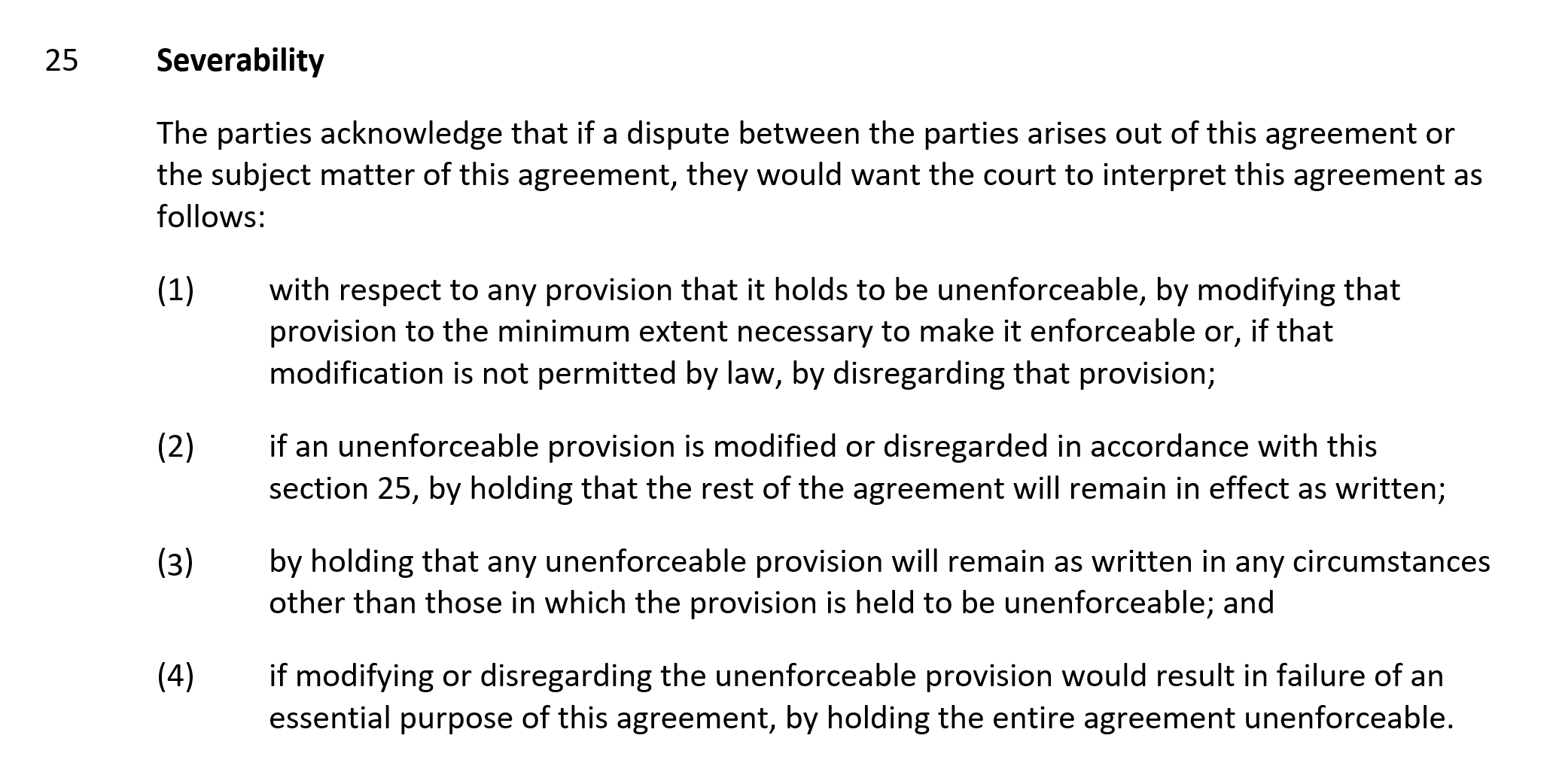

So here’s the whole thing again:

I can’t promise it won’t change, but we’re making progress.

If the parties agree that part of the contract expresses an essential purpose of the agreement, they should say so. I suggest you’d to that in a separate subsection, making the stuff above the first subsection.

***

[Original 30 January 2017 Post]

In this 2012 post I introduced you to my severability provision. I’ve made some adjustments to the enumerated clauses, but what I want to consider now is the introductory phrase. Here’s what it is in the 2012 version:

The parties intend as follows:

And here’s what it is in something I produced yesterday:

The parties acknowledge that if a dispute between the parties arises out of this agreement or the subject matter of this agreement, it would be consistent with the wishes of the parties for a court to interpret this agreement as follows:

This change was prompted by two things.

First, intend makes sense only with respect to that which you control.

And second, I recently completed a manuscript on the ways in which contracts attempt to preempt judicial discretion. That’s relevant for purposes of a severability provision, so I wanted to take a crack at expressing exactly what the dynamic is.

This is a work in progress. What do you think?

To the extent a court is moved to treat a contract provision as severable, or otherwise to interpret a provision in a particular way, based on something the parties say in it, the court is seeking to implement the parties’ stated *intentions*. I think you’re doing violence to your usual posture on “acknowledge” to rephrase as you have, as a party acknowledges something outside its own volition (a fact, for example, about which the other party has knowledge), and here intention is within the parties’ respective control. So what’s wrong with “intend”?

How a contract is interpreted is up to a court. It doesn’t make sense for me to have any intentions regarding how a court acts, as that’s out of my control.

I agree with the premise, up to a point. Courts sometimes do look to the parties’ intentions in interpreting the facts before them. And this is one area in which one gets some client push-back. So if “intend” isn’t the right word, then we need something else (preferably something pithy), and I don’t think “acknowledge” is quite it. Mark’s suggestion makes sense, following along the lines one uses in a forum clause where the parties agree not to raise forum non conveniens or lack of personal jurisdiction.

Here’s another version. Not claiming it is better, but it may provide food for thought:

If the

parties litigate a dispute between them in relation to this agreement or its subject matter, they will ask the

court to interpret this agreement as follows:

The difference between my effort and yours (my effort was a “best” one, I assure you) is that mine assumes that it’s entirely up to the court to decide. Yes, the parties try to convince the court, but “ask” perhaps suggests that the court is there to respond to requests.

And isn’t a problem with “shall ask” the fact that if it comes to that, they’ll be in a fight, so one of them will certainly not be in a mood to cooperate.

How about using the present tense “ask”? As Ken says “will ask” might sound like “shall ask” and that in turn would suggest a contractual obligation. If the parties ask now, when the contract is written, the request can be heard in the future by the court.

I would expect an English judge to respond well to such a clear request stated in the contractual documents.

If, as we know, the basic tenant of contract interpretation is to look at the four corners of the document for evidence of the parties intention, I am not certain that the revised version is any better than the original. If the expressed intent contained in the document is for a certain interpretation of the contract as agreed to by the parties, a court is going to have to really come up with some good reasons why it has disregarded the parties’ intention when it comes to severability of clauses or interpretation of the contract.

You could add some clarifying language:

“If a dispute arises between the party related to this agreement or the subject matter of this agreement, the parties intend as follows:…”

The main reason for the switch is that in the course of discussing the matter on such exalted platforms as Twitter, I’ve come to the conclusion that it makes sense to use “intend” only with respect to stuff you control.

In the spirit of MSCD 17.14, which counsels us to avoid “in the event of”, wouldn’t it be clearer to say: “The parties acknowledge that if a dispute between the parties arises out of this agreement or the subject matter of this agreement, it would be consistent with the wishes of the parties for a court to interpret this agreement as follows:”?

Done! Thank you. Of course I knew that in the event of was lame, but I didn’t have the critical distance to come up with something better.

I’ve stopped including severability rules in my contracts and largely ignore them in contracts written by others because judges going to sever or not at their discretion, not my client’s or the other guy’s. Am I doing it wrong? I’m looking forward to your manuscript.

Also, why the distinction between “arising out of this agreement…” and “…the subject matter of this agreement…” Can’t we just write: “If a dispute arises, the parties would want the court to…”

I share your skepticism. My focus here has been to come up with optimal language, if you’re going to do the severability thing at all. I could do with taking a step back now and deciding when to use it, if at all.

The wording aims to cover claims under the contract and other claims (including tort claims). I use it in dispute-resolution provisions generally. But in a particular contract, instead of the subject matter of this agreement, I’ll refer to what the contract’s actually about.

Nit picking, but why say “would want” instead of just “want”?

Because the dispute doesn’t currently exist. For now, that will have to do!

I think it misconceives the drafting problem to think of severability provisions as trying to preempt judicial discretion more than any other kind of contract provision does. The approach I favor is to make the severability provision no more or less directive than definitions or other internal rules of interpretation. The following example doubtless needs work, but illustrates this approach:

*If a provision of this agreement would in some circumstance be unenforceable, and a change consistent with the essential purpose of this agreement (such a change, a ‘Saving Change’) would make the provision enforceable in the circumstance, the provision means what it would have meant had the Saving Change been part of the provision at signing.

*If no Saving Change is possible and this agreement would fail of its essential purpose without the unenforceable provision, the agreement is entirely unenforceable.

*If no Saving Change is possible but this agreement would not fail of its essential purpose without the unenforceable provision, this agreement means what it would have meant had the the unenforceable provision not been in this agreement at signing.*

Your approach, although interesting, ignores the jurisprudence on how courts handle unenforceable contract provisions. It’s also artificial, in that it attempts to grab interpretation back from the courts after they’ve gotten their hands on the contract.

The more I reflect on severability provisions, the more I join ‘Paco Trouble’ and Ken in skepticism.

What if there is more than one possible change that would make the provision enforceable? Do I want a court deciding which is the “minimum” one?

And do I want the court deciding the “essential purpose” of the contract? (Usually it’s that Acme and Widgetco both make money.)

Maybe this is an area that can’t be thought through well in the abstract, but only in particulars. I also sense that severability provisions can look like other things.

If so, I offer the following for analysis in this context:

‘The Employee shall not cut men’s hair professionally for ten years after leaving AcmeCuts’ employ. If ten years is uneforceably long, the noncompetition period will be nine years. If nine years is unenforceably long, the period will be eight years.’ Etc. (Talk about cutting off a dog’s tail by inches!)

‘The Employee shall not cut men’s hair in the EU during the Noncompetition Period. If the EU is an enenforceably large Noncompetition Zone, the Zone is the Benelux Countries. If that Zone is unenforceably large, it is Belgium only. If Belgium is too large a Zone, the Zone is the City of Antwerp’.

That approach might be struck down as in terrorem, but it guides the court very specifically as to the parties’ conditional intentions without asking the court to draft minimum modifications or determine essential purposes.

In a common-law jurisdiction that requires restraints on employment to be ‘reasonable’, I wonder what a court would make of a provision that the Employee may not compete ‘for as long a period and over as large an area as is permissible under the law of jurisdiction X’.

Another variation might be based on Ken’s recommended ‘best efforts but not exceeding a cost of €2000’ approach: ‘The Noncompetition Period is 18 months or whatever shorter period is enforceable’.

Ken:

In (1) I’d use “for” in place of “with respect to.”

In (2) I’d start with “if it modifies or disregards an unenforceable provision …”

And why not use language of obligation imposed on someone other than a party to the agreement? E.g., “If [blah blah blah], the court must [blah-de-blah]”?

Chris

I’ll lock myself in a darkened room to consider your two suggestions. Regarding using the court must, I recently submitted to a journal an article on why there’s no point telling courts they must do stuff.

Ken:

You’d be amazed at how deferential some courts will be to rules that the parties impose on the courts, as long as those rules are properly within the bounds of a contract. Some types of severability may cross that line, where there’s a public interest at stake, such as competition. I’d still use the “must” version because your version seems wishy-washy enough that courts would be more inclined to ignore it.

Chris

I’ll be glad to see the article, but I’m struggling to see the difference in substance between what on its face is *not* telling a court what to do (eg ‘in this agreement, the following definitions apply’) and what on its face *is* telling a court what to do (eg ‘in construing this agreement, a court must apply the following definitions’).

Isn’t the obvious lesson that when a drafter can draft a provision tactlessly or tactfully, tactfully is better?

There’s a big difference between the parties agreeing to the terms of the deal and the parties telling a court how to behave.

The former shows tact and the latter not. A drafter tackling the possible invalidity of a provision should write it up as a conditional deal term, not as conditional order to a court. ‘If A, then B’, not ‘If A, then the court must do the following’.

I agree and would tentatively suggest there are several categories of telling the court what to do, including.

(1) telling it how to exercise a discretion to give an equitable remedy;

(2) telling it that you want it interpret the contract in a way that makes the obligations enforceable, if necessary by re-writing the contract.

Under English law and practice, (1) is unlikely to achieve much, and might get up the court’s nose; and (2) may meet strong resistance as being impermissible under English law. The blue pencil test tends to allow deletion of words and phrases rather than wholesale rewriting. I would say there is less of a tradition than there seems to be in the US of the court doing what the parties tell it to.

I like the revised language, Ken. I would be pleasantly surprised if a trial court judge would actually take the time to apply it in reaching a decision (unless one of the parties submits findings of fact and conclusions of law on it for him/her).

When posts are scarce, one meditates on those already ‘up’. Here’s a revised version of your revised version. Among other things, it barks no orders at courts, but rather states what the deal is if a provision is unenforceable:

25. Severability. If a provision of this agreement is unenforceable, the following rules apply:

(1) the unenforceable provision will be valid as modified to the minimum extent necessary to make the provision enforceable, but if such a modification is impermissible, the unenforceable provision will be void;

(2) if this section 25 modifies or voids a provision, the rest of this agreement will remain in effect unless the modification or voidness defeats an essential purpose of this agreement, in which case the entire agreement will be void [and the parties may seek remedies as upon a rescission?] ;

(3) if a provision is unenforceable in some circumstances but not in others, it will remain in effect as written in those other circumstances, unless that remaining in effect will defeat an essential purpose of this agreement, in which case the entire agreement will be void [and the parties may seek remedies as upon a rescission?].

I’ve been a long-time fan and lurker on this site, but this is a first-time post. Please be gentle! I typically have my severability provisions include an obligation on the parties to work together if a provision is tanked (here’s the gentle part — this language admittedly has not been run through compliance with MSCD): Upon such determination that any term or other provision is

invalid, illegal or unenforceable, the parties hereto shall negotiate in good

faith to modify this Agreement so as to effect the original intent of the

parties as closely as possible in a mutually acceptable manner in order that

the transactions contemplated hereby be consummated as originally contemplated

to the greatest extent possible.

Thoughts as to that concept?

What’s your latest take on severability? Am I missing a more recent post? I saw no severability provision in a draft confidentiality agreement generated from your questionnaire several months back and thought maybe you concluded those provisions are unnecessary.