Last week I started three series of my online course Drafting Clearer Contracts: Masterclass for an Asian company with global operations.

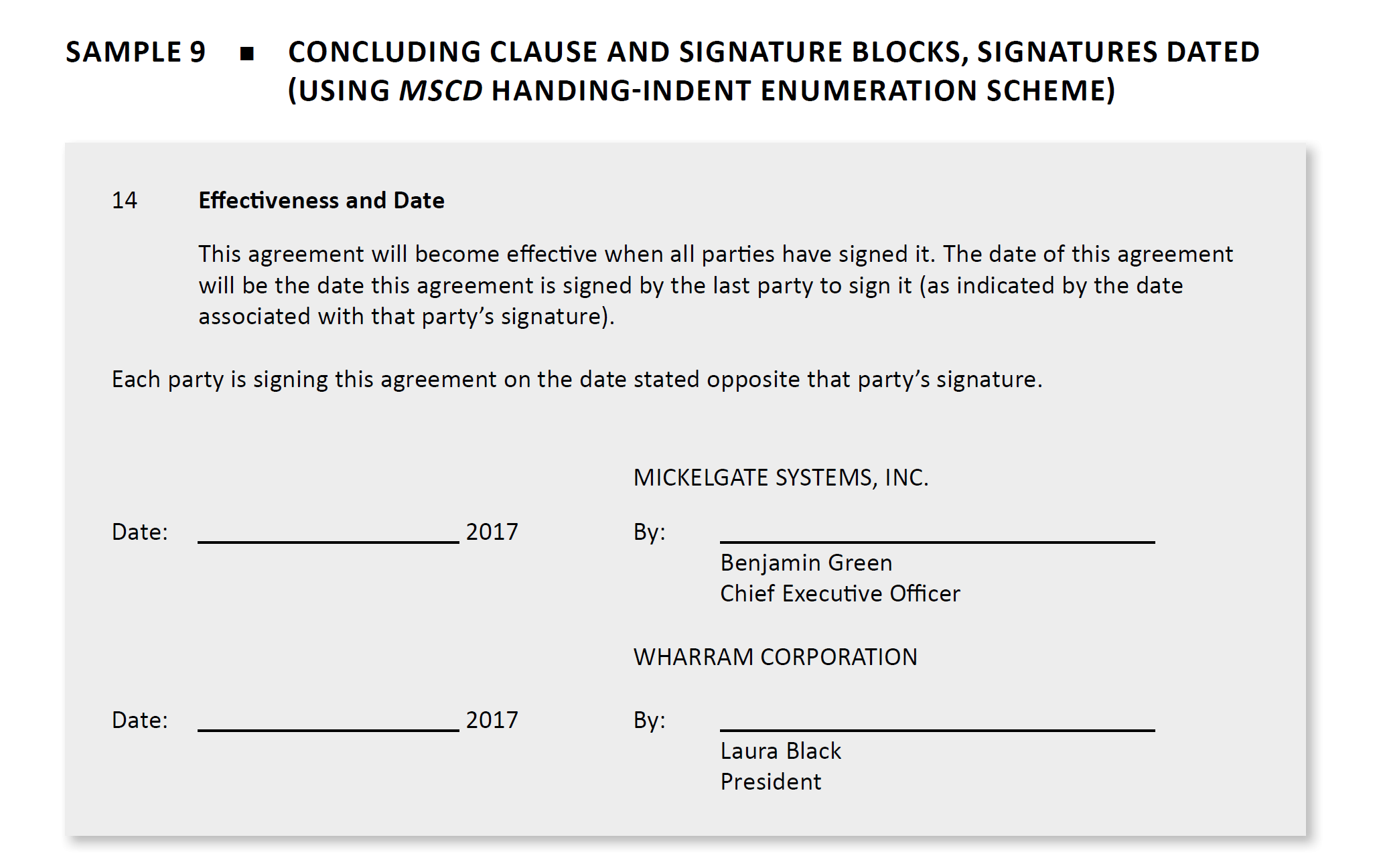

In the first session of Masterclass we discuss the front and back of the contract, just to get everyone used to comparing dysfunctional traditional contract language and the clearer alternative. I flashed on the screen a slide containing one of my two versions of the concluding clause. It’s the same as what’s in this sample from MSCD:

I made a couple of low-key remarks and was prepared to move on when one of the participants asked this question: “Do you need the word stated?”

I paused, uncertain, then asked the participant to repeat the question. Stated? It’s nothing I had ever thought about. In fact, I’ve not thought about this version of the concluding clause in years.

I prevaricated a bit. For one thing, I wasn’t sure that the version on my slide was identical to the one in MSCD. (It is.) I said I’d think it over.

And I will think it over. Should I eliminate stated? What do you think? But what I do know is that the participant who asked the question gets my highest honor, the Sparkly Blue Ribbon for Semantic Acuity. (It exists only in my imagination.) They spotted a potentially redundant word that I’ve never thought about. In my world, possibly omitting an extra word from a standard component is a big deal.

Receiving this kind of observation is a great fringe benefit to engaging with the world. This bodes well for the rest of these series of Masterclass.

I would be inclined to delete the whole sentence: it is clear when each party is signing the agreement.

Definitely. To my English mind, “stated” is not quite the right verb anyway – I might have used “shown” or somthing, although in reality I would probably have gone with whatever the author of the precedent offered. Thanks for making me think about it!

Do we need the sentence at all? What information does it provide that is not already obvious from the rest of the document?

More specifically, there are two scenarios:

1. The parties have actually signed the agreement on the date opposite their signatures, in which case its kind of obvious; or

2. They haven’t, and they’re trying to “back/forward-date” the agreement by indicating a different date opposite their signatures. In this case, perhaps it would be better to recflect something to that effect in the sentence (some kind of explicit deeming provision about the dates of the signatures?)

Using fake dates next to signatures would be a bad idea.

Here’s what I say in MSCD: “You could conceivably dispense with the concluding clause, as it states the obvious, but it’s best to retain it, in an appropriate form—it eases what would otherwise be an abrupt transition to the signature blocks.” And it’s only one line.

Furthermore, it’s conventional to have a concluding clause, so I’m giving people a component they expect, but mine is way simpler and clearer.

Or more simply: A blank line beneath each signature line, and underneath it the words, “Date signed,” to reduce the chances that a signer will leave the date blank on the assumption that “someone else” will take care of it. (And use a two-column Microsoft Word table to align the two parties’ signature blocks horizontally.)

EXAMPLE:

AGREED:

ABC CORPORATION, by:

____________________

Amy Adamson, CEO

____________________

Date signed

AGREED:

XYZ, INC., by:

____________________

Signature

____________________

Printed name

____________________

Title

____________________

Date signed

Incidentally, the backdating problem is a real one: A former CEO of software giant Computer Associates spent ten years in federal prison for securities fraud for, among other things, the company’s practice of the “35-day month” at the end of the quarter: Customer contracts would not-uncommonly be backdated — and the revenue improperly booked in the just-ended quarter, instead of in the then-current quarter when it should have been. In addition, the CFO, general counsel, and head of worldwide sales all spent time in prison or home detention, and the GC was disbarred. (Citations in my course materials.)

I have a question about the effectiveness clause – the agreement will be effective „when all parties have signed it“. Doesn’t that cause some problems if the agreement is signed without all parties being present at the signing, e.g. if it is signed by mail?

Suppose Party A signs the agreement on 3 March 2017 and sends the signed originals to Party B. The CEO of Party B then signs the agreement on 7 March 2017 (and marks this date on the agreement) but leaves the agreement on his/her desk. A week later Party A enquires if the agreement has already been signed after which a secretary of the CEO of Party B finally takes the fully signed originals of the agreement from the CEO’s desk and sends one original back to Party A who receives the agreement on 31 March 2017 and discovers that the agreement is effective already from 7 March 2017. Imagine if there is some deadline for Party A in the agreement that starts running from the date of effectiveness – it might lapse even before Party A learns of the agreement being effective.

Thus, should not the effectiveness clause be drafted differently in case the agreement is not signed in presence of both (all) parties (e.g., linking the effectiveness to the first signing party being notified of the signing by the other party)? And, if the agreement is in fact signed in presence of both (all) parties, can’t the clause be simplified by just saying „This agreement will become effective on ________ 2017“ (where the parties will fill in the actual date on signing)?

Sorry if my question is foolish, I am not a US lawyer.

This scenario is a strong reason for using electronic signature services like Docusign or Hellosign. You don’t need all the parties in the same room, you can track who has signed and who hasn’t, you can set the order in which people sign, you can control where they sign so they don’t mess up, and you automatically are notified when everyone has signed so you can retrieve the fully-signed document and circulate it to the parties. This software will make your practice so much easier, and it is not expensive at all.

I fully agree. Unfortunately, there are some transactions that still require (at least in some jurisdictions) hard-copy form and handwritten signatures, sometimes even with some form of official certification (e.g., real estate transfer deeds).

Hopefully the experience of a global pandemic will force everyone to join the 21st century.

How about “next to its” or “across from its” rather than “stated opposite that party’s”?

Sure.

After a few more months, this looks even more sensible.