Over dinner recently, a transactional lawyer told me he makes a point of including a duck in each draft he sends to the other side. But he didn’t actually use the word “duck.” That’s my word, thanks to the great Alex Hamilton, who pointed me to this post on the Coding Horror blog, which includes the following definition of duck:

Over dinner recently, a transactional lawyer told me he makes a point of including a duck in each draft he sends to the other side. But he didn’t actually use the word “duck.” That’s my word, thanks to the great Alex Hamilton, who pointed me to this post on the Coding Horror blog, which includes the following definition of duck:

A feature added for no other reason than to draw management attention and be removed, thus avoiding unnecessary changes in other aspects of the product.

The post goes on as follows:

This started as a piece of Interplay corporate lore. It was well known that producers (a game industry position, roughly equivalent to PMs) had to make a change to everything that was done. The assumption was that subconsciously they felt that if they didn’t, they weren’t adding value.

The artist working on the queen animations for Battle Chess was aware of this tendency, and came up with an innovative solution. He did the animations for the queen the way that he felt would be best, with one addition: he gave the queen a pet duck. He animated this duck through all of the queen’s animations, had it flapping around the corners. He also took great care to make sure that it never overlapped the “actual” animation.

Eventually, it came time for the producer to review the animation set for the queen. The producer sat down and watched all of the animations. When they were done, he turned to the artist and said, “that looks great. Just one thing – get rid of the duck.”

My dinner companion had exactly this effect in mind. He creates what he thinks is an even-handed draft, then he adds a provision that clearly overreaches. His theory is that the other side spots that provision, asks him to remove it or tone it down, and otherwise leaves the draft as is. In other words, the other side asks him to get rid of the duck. Removing the duck makes the lawyer for the other side feel like they’ve done something useful. But for presence of the duck, they might create mischief by changing something else—something that makes sense—just so they can show their client that they had added value.

My dinner companion obviously thinks this strategy works for him often enough to make it worthwhile for him to stick with it. I don’t do deals, so I have no experience with this issue. But by temperament, I’m inclined not to play games. And this approach could conceivably be counterproductive: once the other side makes a change, they might find it easier to make further changes.

What do you think?

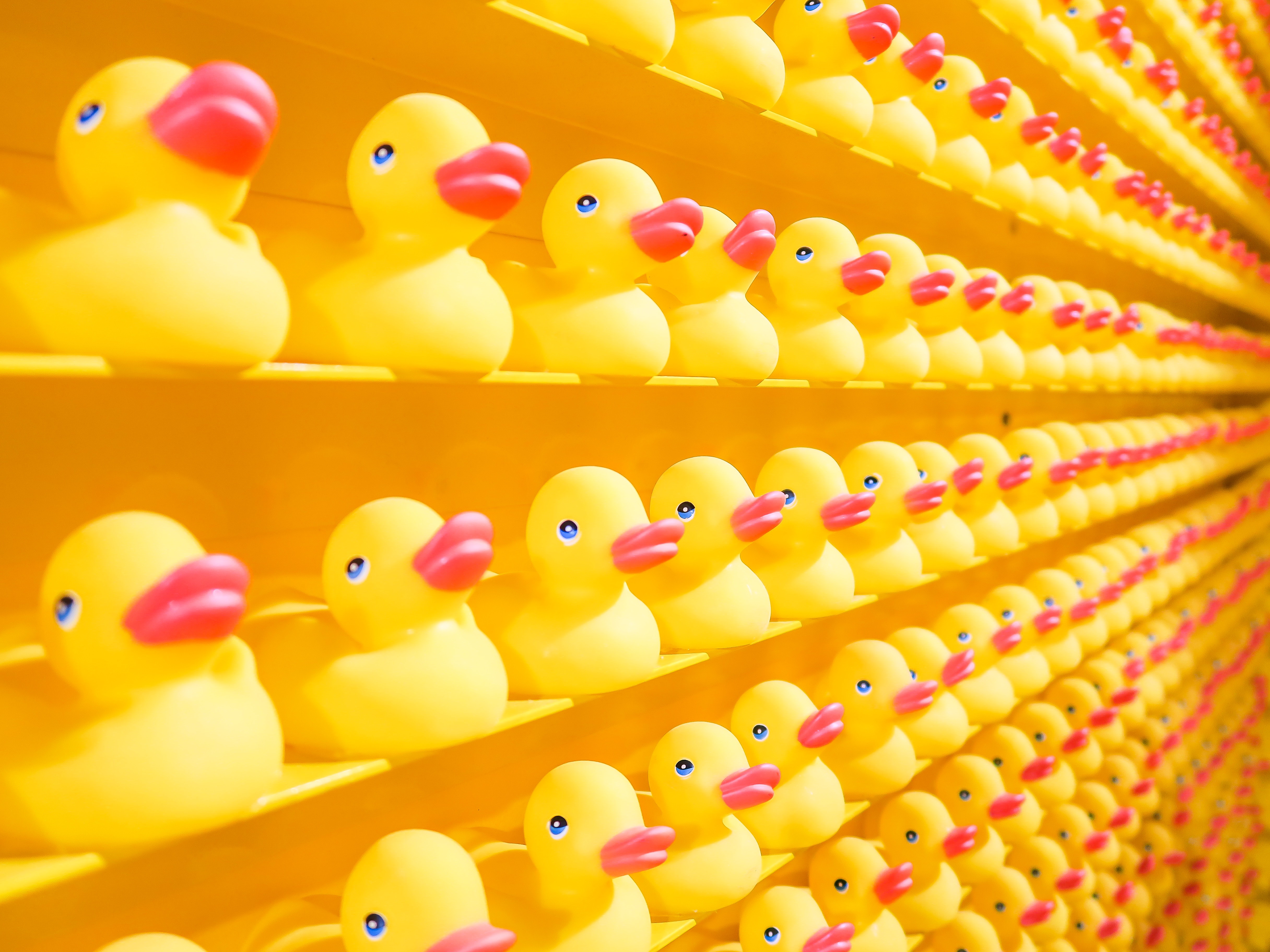

(Photo by Joshua Coleman on Unsplash.)

Nice post. This strategy is referred to as the “rejection-then-retreat” rule (a/k/a a “weapon of influence”) in the seminal book “Influence” by Robert Cialdini about psychological persuasion. Although I have never attempted this approach, I am sure that it is a tool that could be used effectively from time to time.

Thanks for that context!

I actually used this strategy today, before I knew it had a name… In my case, I reviewed a contract and wanted to make one change, but inserted another one that I am willing to give up as a compromise to keep the main item.

Interesting, but I think what you did is horsetrading, which is slightly different. By contrast, one puts in a duck not to extract concessions but to act as bait for people who feel compelled to change stuff, whether or not it’s helpful to do so.

The contract will — like it or not — lead to an impression regarding the credibility and sophistication of not just the counterparty but the lawyers representing that party as well. So there’s that to think about.

Also I think such a “duck” results in an unnecessary break in the process that contributes in the end to whether deal fatigue manifests itself later on.

I much rather like saying to my client, “That document’s good. You can sign.” The alternative is “Well, you have this weird provision that …” and the client says “Is it something we need to take care of, do you really think?” and the lawyer says “Well I think so because …” And that’s some BS, if I do say so myself.

> I much rather like saying to my client, “That document’s good. You can sign.”

That works when you’re a seasoned lawyer. On the other hand, if you’re a junior lawyer, your supervising partner might wonder whether you did a sufficiently-thorough job in reviewing the document.

There’s an old saying in the military that when you’re being inspected, you should make everything ship-shape, but then [mess] things up just a little bit, to give the inspectors something to find, because they’ll keep looking until they do. (Last year one of my students, a veteran, added, “And make sure it’s something they can’t throw ….”) The inspectors want to report at least a few discrepancies to their superiors, to prove that they did their jobs instead of making early beer call at the NCO club.

I’d never seen this strategy referred to as a “duck” before, but it fits.

Ha ha, I was just working my way down and about to comment on the military inspections analogy. At the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst (which West Point is based on), room inspections were normal for the first five weeks as part of the process of introducing people into the military and inculcating high standards.

The Directing Staff would invariably find something in each person’s room to focus on/criticise – otherwise inspections would take seconds as they walked around a room, looked at lots of very highly polished things, and then moved on to the next room.

Rather than have something picked up for being supposedly imperfectly cleaned or polished, the trick was to have a “Distractor” which naturally caught the eye, and became the focus, if not even a topic of conversation. The most effective example in my time, was one of the girls in the female platoon, who had a “Combat Barbie”.

(Incidentally, the days of things being thrown out of windows are long gone in the British military: that sort of behaviour, along with verbal abuse, was rightly seen as both unnecessary and a reflection of a paucity of language and leadership skills. :)

Thank you for this!

Ken:

Maybe for a document that you think is highly likely to get actual review by a lawyer. What I’m always shooting for when I construct forms is a form that the other side can just accept. Not having to do any negotiation whatsoever is much better than minimizing negotiations by focusing attention on a spurious provision. The presence of that spurious provision will require lawyers who would otherwise OK it to feel like they have to object to it.

Chris

Happens all the time.

I’d distinguish between points added in so someone else has something to do to justify their role, versus points added in so the other side of the negotiation gets to the end feeling there has been give-and-take between peers. Deals can feature one, both, or neither.

I used to think give-and-take was a subspecies of self-justification, and sometimes it is. But experience has shown that’s not always the case. They’re potentially independent.

I can see why it would be tempting to try and out-smart someone who you suspect is just making changes for changes sake or to justify their existence. I might try this if I was trying to fend off changes internally.

But as another commenter alluded to, when you’re negotiating with another party, if you’re seen as engaging in tactics that can reflect poorly both on the party you represent and on yourself as counsel. You risk poisoning the relationship before it has even been cemented.

I will stick with putting forth clauses I consider reasonable and if I suspect changes are being made for changes sake, I ask why the other side feels that change is necessary and what purpose it serves (which is also a question I ask myself when I make changes to other people’s drafting). I find that having to answer that question is often enough to fend off unnecessary changes.

There is no question that some attorneys need to demonstrate to their clients that they have provided them value, but I find that is generally not the case when the attorney has a history with their client that extends over many transactions. In the latter instance, there is nothing that attorney would like more than to submit the agreement unmolested to their client for signature. It would be a rare enough event since most agreements that have been submitted, even from large companies, are crappy cut-and-paste documents that, at worst, have been prepared by idiot contract managers or, at best, by inundated in-house counsel.

We bleed all over those documents and return them, a whimpering, quivering shadow of their former selves. No ducks required. Just produce rational, even-handed agreements in Word with proper use of styles and outline numbering (we regard agreement submissions in .pdf as a hostile act) that get the parties right, correctly and consistently use defined terms, and that reasonably and fairly allocate risk.

When we see a properly drafted agreement, we root and cheer for the possibility that we will arrive at the signature line without having made a single revision, and we will generally give the drafter the benefit of the doubt in close calls….sort of like a well-executed neighborhood play at second base.

And by the way, if you format it in columns with 8pt typeface, you are off to a very bad start.

– Krumhorn

There’s no need to include a duck. Every contract of any length, even one that is relatively even-handed, has some provisions that are “must-haves,” some that are “nice to haves,” and some that are a bit of a stretch. If nothing else, the limitation of liability provision always provides some room for dickering if the parties are so inclined. Why put in something extraneous when you have valid negotiating points to work with?

Dubious. In the context of contract negotiations, how often do you, even in an even handed draft, get agreement on all issues except the one duck?