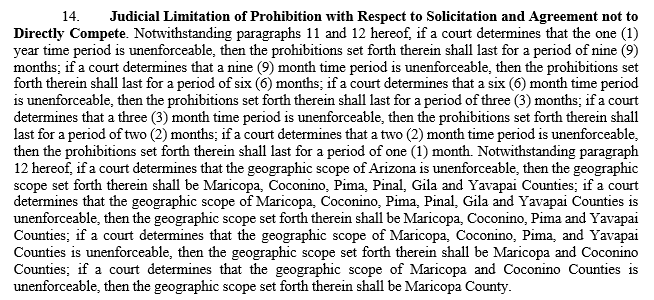

Check out the provision above. It was put on Twitter by Aiden Durham, who said, “There’s gotta be a better way?!” Filthy McNasty tagged me in the ensuing thread, so here we are.

Check out the provision above. It was put on Twitter by Aiden Durham, who said, “There’s gotta be a better way?!” Filthy McNasty tagged me in the ensuing thread, so here we are.

The extract above is from an Arizona contract. Arizona has a “strict blue pencil” approach to enforcing post-employment restrictions on employees (generally known as “restrictive covenants”), which means that courts are permitted to eliminate only those unreasonable provisions that are grammatically severable and are forbidden from rewriting restrictive covenants.

A response by Arizona drafters has been “step-down provisions,” which contain an array of progressively less-onerous options for courts to choose from if they find the most-onerous options unpalatable.

I’m now going to rely on a great 2019 article in the Arizona State Law Journal by Scott F. Gibson entitled Restrictive Covenants Under Arizona Law: Step Away from the Step-Down Provisions (PDF here). Just to give you an idea of the beat-down Mr. Gibson administers to the idea of step-down provisions, here are a few extracts (footnotes omitted):

But even Arizona’s strict blue pencil rule may give the employer an unfair drafting advantage. Because the court has the authority to parse through reasonable and unreasonable portions of the restrictive covenant, the court will enforce some agreements that were drafted with unreasonable restrictions. More importantly, the employer unfairly benefits from the uncertainty arising from these overly broad restrictions.

…

Step-down provisions conflict with these fundamental principles of Arizona law because they (1) allow the employer to improperly transfer its burdens to the court, (2) fail to outline the employee’s obligations with sufficient specificity, (3) establish conflicting restrictions that cannot in good faith be reconciled as being reasonable, (4) authorize the court to rewrite rather than edit an overly broad restriction, and (5) create an in terrorem effect that improperly allows the employer to prevent competition per se through an overly broad restriction. We will discuss each of these failings below.

…

A step-down provision indicates that the employer has not given sufficient consideration to either (1) the actual scope of its business interest or (2) the proper method for protecting that interest. The employer has neglected its duty to narrowly tailor the restriction to its legitimate business interest and has instead turned that duty over to the court. The employer’s failure to meet its burden–and its cavalier attitude toward its responsibilities—reflects that it was focused on preventing competition per se and not simply avoiding unfair competition. Arizona law precludes the employer from shirking its responsibilities and turning them over to the court.

…

Courts would not enforce any other contract that contained key provisions that are as vague as those in a step-down provision. No court would enforce an agreement where one party agreed to pay either $50 or $150 or $500 depending on what the court determined was “reasonable” under the circumstances. Step-down provisions ask the court to “do for the employer what it should have done in the first place[—]write a reasonable covenant.” If the employer is unable to reasonably and coherently state a limited restriction based on legitimate business interests, it should not ask the court to fix its own failings.

…

Step-down provisions create a truly ominous restrictive covenant, i.e., a covenant the employer believes “will be pared down and enforced when the facts of a particular case are not unreasonable.” Step-down provisions violate the requirement of good faith by ignoring the “bottom line” validity of the restriction and requiring the court to act as scrivener to prepare the restriction the parties should have entered into if the employer had done its job.

…

Step-down provisions violate Arizona law because they require the reviewing court to rewrite—rather than edit—the restrictive covenant.

…

Honorable employees will abide by reasonable restrictive covenants. But when the covenant contains step-down provisions, the employee cannot be certain what she can and cannot do. Is she precluded from practicing her trade within five miles of each Service Location for two years? Or is she restricted within two miles for six months? Or is the restriction something in between these extremes? While an employer may not fear filing suit to get the trial court to determine the scope of the restriction, most employees are hesitant to do so. So rather than litigate to prove that a reasonable restriction is no greater than two miles for six months, the employee will succumb to the in terrorem effect of the step-down provisions and either seek a new trade or practice her trade outside the five-mile restriction for two years. And the employer benefits from the in terrorem impact of the restriction, even though it has conceded that five miles and two years are unreasonable restrictions, as witnessed by the inclusion of two lesser geographic restrictions and three shorter temporal restrictions. This result is inconsistent with Arizona law.

You won’t be shocked that I endorse Mr. Gibson’s conclusion: “Attorneys who wish to best protect their clients’ business interests will step away from step-down provisions.”

I expect that step-down provisions can be found in restrictive covenants governed by the laws of other “strict blue pencil” states. And for all I know, step-down provisions might occur in other kinds of contracts. But their shortcomings mean they’ll be a liability wherever you find them.

Doesn’t this assume that the exercise determining the employer’s ‘legitimate business interest’ is an exact science (in terms of geography and time), beyond dispute or opinion?

If it is not an exact science (i.e. an employer, employee and a court could come to a different view on what is reasonable), isn’t it reasonable for an employer to cover different cascading obligations as Plan B then Plan C etc. if the court disagrees with the employer (and where the court has final say)?

If it is an exact science, how do employers work this out?

It’s not at all an exact science: it’s vague. The problem is that step-down provisions are gaming a vague system.

And if you don’t game it, take a guess and get it wrong, does this mean the employer gets no protection at all? Seems hard to advise clients on this. At least the cascading obligations guides the court on severing unenforceable obligations.

Gibson misses the point that the step-down provisions are merely fallbacks — by definition the employer is asserting its position that the original one-year period and geographic scope are reasonable; there’s nothing at all vague about that.

(My own beef with the quoted provision is that it’s a “wall of words” that could be stated much more readably as a table.)