If a contract usage has been around long enough and appears in enough contracts, you’ll find people to defend it, no matter how archaic or otherwise nonsensical it is.

A case in point: yesterday Ryan McCarl did this LinkedIn post about the word witnesseth, calling it a “meaningless incantation.” That prompted one reader to say this (in two comments I’ve consolidated):

“Witnesseth” in legal practice is still very common in contracts in several jurisdictions. And archaic or not, I don’t mind it.

One useful thing that I can think of immediately, is that it serves as a marker formally introducing the substantive terms and conditions of the agreement. I probably could find others if I put my mind to it.

So this reader says witnesseth is benign—no, in fact it’s useful! That’s the legalistic mind in action.

Legalism means strict, literal, or excessive conformity to the law or to a religious or moral code; legalistic is the related adjective. In connection with contract drafting, I use legalistic to mean excessive conformity to the dysfunction of mainstream contract drafting. For the legalistic mind, if something features in mainstream contract drafting, it must be legitimate, even if, as in the case of our commentator, they offer only one mistaken justification and simply assume there are probably others.

Why “mistaken”? Because generally, witnesseth isn’t used to introduce the substantive terms of the contract. Instead, it’s used by the more archaic-minded among us to introduce recitals. A simpler alternative would be the heading Recitals; even clearer would be Background. Me, I don’t use any heading. Here’s a comment I added to Ryan’s post:

I recommend not giving a heading to the recitals or any other part of the front and back of the contract. If someone knows what recitals are, they won’t need them flagged. If they don’t, the heading “recitals” won’t do them any good. And if you put stuff in recitals that shouldn’t be there, giving them the heading “Recitals” won’t help. But if someone really has the urge to use a heading, I’d go for “Background”.

What the commenter to Ryan’s post has to say reminds me of a comment to my recent post on using only words to express numbers (here). Here’s part of the comment:

I just had a lawyer tell me in a very condescending and nasty fashion that it was A REQUIREMENT (and he said it in all capital letters, just like that, A REQUIREMENT) to put both the words AND the numbers in a contract, that he had to fix my form (!!) because I was WRONG (again, spoken in all caps).

Yes, the legalistic mind is characterized by dogmatic certitude. I suggest that the legalistic reaction is driven by cognitive dissonance—the panic that comes on when someone suggests that the way you’ve been doing things since forever is laughable.

Further reading:

- See this 2013 blog post for more about cognitive dissonance and contract drafting.

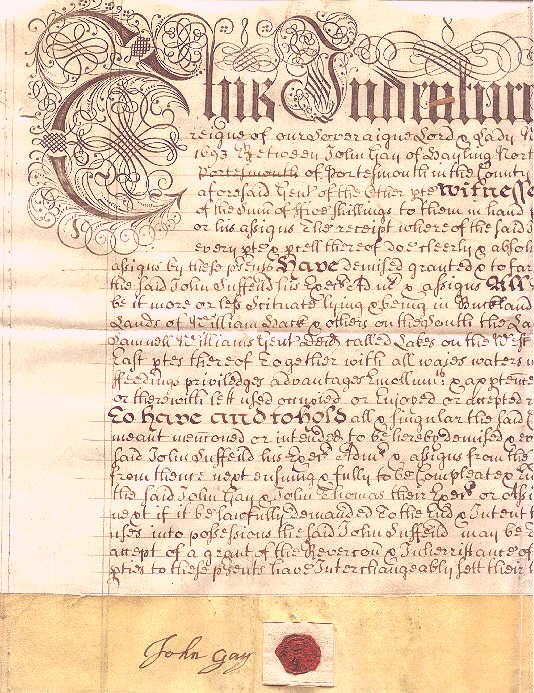

- See this 2017 blog post in which I channel the mindset of someone who uses witnesseth and suggest the following: “If your contracts matter and your lawyer serves up witnesseth, get your lawyer to change their ways. Or change your lawyer.”

- See this 2017 blog post on the roots of all-capitals archaisms.

- And—spot the odd man out—see this recent blog post about upcoming Drafting Clearer Contracts training.

A mountain is being made from a molehill here.

‘Witnesseth’ is as defensible as the following sentence:

‘This agreement between Abel and Baker serves as evidence [= “witnesses”] that, for the following reasons [insert recitals], Abel and Baker are agreeing as follows [insert full agreement]. As evidence that they are agreeing to the above [= “in witness whereof”], Abel and Baker are signing this instrument below.’

It would be possible to use other language to describe the relation between the instrument and the contract, but the ‘witnesseth/in witness whereof’ formulations are innocent and workmanlike.

In my view, we have over the centuries come to view the written instrument as the contract itself rather than mere evidence of the parties’ meeting of the minds. And that’s okay. We don’t usually speak and think of the agreement and the instrument embodying it as two different things, like testimony and a transcript, or a territory and a map of it.

I say ‘usually’, because sometimes we do make the distinction, as when the signed instrument is destroyed. We look for other evidence of what the parties’ ‘contract’ was, in the sense of their meeting of the minds. We understand that the instrument and the agreement are two different things, the former ‘witnessing’ to the latter, and that the accidental destruction of the instrument leaves the contract in full effect.

A usage that’s old, even if it’s blindly adhered to, isn’t necessarily bad or wrong, let alone ‘change my lawyer’ horrific. I think ‘witnesseth’ is an old formulation that’s fine as long as it’s understood in its ‘gives testimony’ sense and updated appropriately. Let’s die on some other hill.