I’m a big believer in the notion that until you name a phenomenon, you likely don’t understand it thoroughly. So I’ve given names to plenty of features of contract topography; I’ll be happy if half of them stick!

In that spirit, my recently published book The Structure of M&A Contracts offers some new terminology. Now that the usual post-publishing dread of looking at the book has worn off, allow me to highlight one of the new terms—the “reference point.” (I recall having seen somewhere a work that in passing offered a comparable term, but my book is the first to discuss the topic at any length, so I figured that gave me naming rights.)

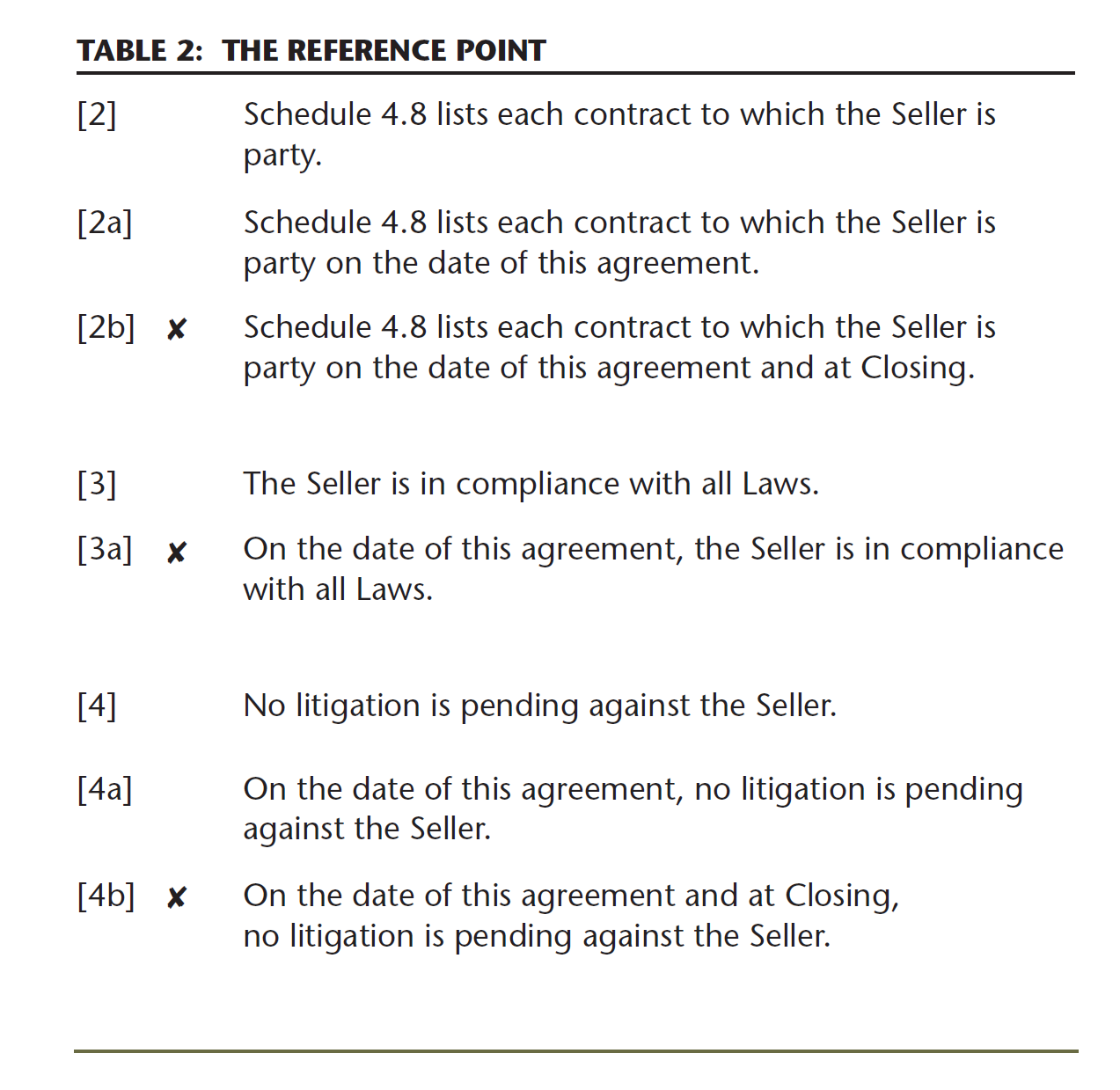

This post is derived from the account in the book. I’ve included below one of the many tables in the book; it’s where you’ll find the numbered examples mentioned in this post.

Effect of the Reference Point

The book addresses in depth the complex question of when a party makes its representations. The short answer is that I recommend using the following representations lead-in: The Seller represents to the Buyer as follows and will be deemed to have so represented again at Closing.

A related question is whether to provide a reference point for a given representation—in other words, whether to have the representation speak as to accuracy of facts only at a point in time stated in the representation.

If no reference point is stated in a representation, then in effect the reference point is when the representation is made. That would be on entry into the contract and at closing, if, as recommended, you use my recommended form of representations lead-in. But if you include a reference point in a representation, that representation would be concerned only with accuracy of facts at that the reference point, regardless of when the representation is made.

Matters Under the Seller’s Control

Whether to include a reference point depends on the representation. Consider first a representation involving matters that are under the seller’s control and that occur in the ordinary course of business, such as the contracts that the seller has entered into. (Assume that the seller routinely enters into contracts.) If no date is stated, then in effect the reference point is when the representation is made. Consequently, if the seller enters into a contract that includes the representation in [2] as well as the recommended representations lead-in and before closing enters into additional contracts, then at closing the representation in [2] would be inaccurate.

The prospect of that likely inaccuracy would present the seller with a potentially uncomfortable choice on entry into the contract: it could curtail its business operations by not entering into any additional contracts or it could enter into additional contracts and face the risk of the buyer’s using the inaccurate representation to walk away from the deal or seek indemnification, or both. The buyer might be constrained by the implied duty of good faith, but that would provide the seller limited comfort.

The seller could get out of this bind by having the buyer allow the seller to make instead the representation in [2a], which would serve to make the date of the agreement the reference point. In response, the buyer could address preclosing change in the matters covered by the representation by putting limits on the seller’s preclosing operations.

For example, the buyer could insist that the contract provide that the seller must obtain the buyer’s written consent to enter into any new contract before closing. But that wouldn’t give the seller any more leeway when entering into contracts than would having the seller give the representation in [2]—even if [2] doesn’t contain a reference point, the buyer could always agree to waive the representation inaccuracy that would result from the seller’s entering into one or more additional contracts. And it could be just as restrictive—except to the extent that it’s constrained by the implied duty of good faith, the buyer could simply refuse to give its consent. So the seller would be justified in countering that it should have to seek the buyer’s consent only if a new contract is not in the ordinary course of business, or that the buyer should not be able to unreasonably withhold its consent.

The more the subject matter of a representation relates to seller actions that are outside the ordinary course of business, the less likely it is that the buyer would be willing to let the seller use the date of the agreement as a reference point and thereby remove from the scope of the representation any adverse changes between the date of the agreement and closing.

For example, an inaccuracy in the representation in [3]—in other words, any failure by the seller to comply with any law—could not reasonably be considered to be something that could arise in the ordinary course of business between entry into the contract and closing. As a result, absent other considerations it would be odd for the buyer to agree to the seller’s giving the representation in [3a].

Alternative [2b] differs from [2] and [2a] in that it includes as reference points both the date of the agreement and the closing. Doing so serves no purpose, given that using the recommended form of representations lead-in allows you to achieve the same result more economically.

Matters Not Under the Seller’s Control

Different considerations apply when the matters addressed in a representation are not under the seller’s control, in that any change between signing and closing could not be addressed by means of an undertaking by the seller. In that situation, whether the buyer would agree to add the date of the agreement as a reference point would likely depend on the nature of the changes that might occur between entry into the contract and closing.

Consider the representation in [4]. If the seller’s business is such that it can expect to be sporadically subject to lawsuits, the seller would likely object to giving that representation—it could reasonably claim that it would be inappropriate for it to be subject to the risk that the buyer would refuse to close, or would bring a claim for indemnification, because one or more ordinary-course lawsuits are filed against the seller between entry into the contract and closing.

If the buyer agrees to add the date of the agreement as the reference point, as in [4a], it could protect itself by making it a condition to closing that the seller not be subject to any litigation commenced between signing and closing. This would constitute what I call a “gap-closing condition.” (A chapter of the book discussed the different kinds of conditions.) Although that would ensure that the buyer couldn’t bring a claim for indemnification if one or more lawsuits were filed between signing and closing, the seller might nevertheless balk, on the grounds that the buyer shouldn’t be able to walk because of insignificant lawsuits. One way to address this concern would be to add a “material adverse change” qualification to that condition or to have the condition exclude lawsuits in which the amount at issue is less than a stated dollar amount.

Of course, instead of adding that condition, the parties could agree to so qualify the representation, but the buyer would likely consider that the seller should be willing to give an unqualified representation regarding litigation pending on the date of the agreement.

Like [2b], example [4b] includes as reference points both the date of the agreement and the closing. And as with [2b], that formula serves no purpose.

***

For more about the book, clicking here will take you to the West LegalEdcenter page for the book, and clicking here will take you to a PDF of chapter 1. For the time being, the book is available only by calling West LegalEdcenter at (800) 308-1700—I apologize for that inconvenience. And click here to go to the West LegalEdcenter page for the related webcast that I did with Steven Davidoff, noted M&A guy and New York Times “Deal Professor.”