Over the years, I’ve written plenty about the practice of expressing numbers using both words and digits, as in five (5) days’ notice.

In MSCD, I recommend using words for one through ten and digits for 11 and up (with some obvious exceptions). I also discuss using only digits. (Go here for an extract of the relevant pages.) But I’ve never considered using only words!

Thanks to this LinkedIn post by Nick Bullard revisiting using both words and digits, I discovered that at least one person thinks using only words is the way to go. Commenter Christof Grofcsik says here, “So, if you’re dropping the [words-and-digits] convention, you should drop the numbers not the words. Much easier to make an error or counterfeit the numbers than the words.” And if one person voices an opinion on LinkedIn, it’s likely others hold that opinion too.

Does using only words offer any advantages over using only digits? Christof says it reduces the risk of an error in stating the number in question. Christof must be referring to typos that result in a number having one or more digits too many or too few, or a number using one or more digits that are the wrong digit, or a number with the decimal point in the wrong place. (Here’s the definition of typo offered by The Free Dictionary: “An error while inputting text via keyboard, made despite the fact that the user knows exactly what to type in. This usually results from the operator’s inexperience at keyboarding, rushing, not paying attention, or carelessness.”)

Such typos do happen. For example, in a mortgage prepared in New York in 1986, the principal amount was erroneously stated as $92,885 rather than $92,885,000. The result was “a spate of litigation, hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees, millions of dollars in damages and an untold fortune in embarrassment.” David Margolick, At the Bar; How Three Missing Zeros Brought Red Faces and Cost

Millions of Dollars, N.Y. Times, 4 Oct. 1991.

Here’s another example, to the opposite effect, from this 2010 post on Footnoted: In an exhibit to an employment agreement filed on the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s EDGAR system, the company undertook that in addition to paying the executive’s moving expenses, “in consideration of other relocation expenses that Executive and his family will incur, $87,500,000 will be paid upon the Effective Date of the Agreement and $87,500000 will be paid upon final relocation to Atlanta, Georgia.” The intended figure was $87,500.

But for some perspective, two points. First, using only words to express numbers might protect against typos, but it doesn’t protect against making plain old mistakes. For example, see this 2017 blog post about a severance agreement that provided for $2,747,400 in severance pay instead of the $80,805.97 that the parties had previously agreed on. The error arose because the company’s HR person put in the contract the total amount of severance when they should have put in the amount per week. The result was that the total severance amount was 34 times what it should have been. The HR person didn’t make a typo; they made a mistake.

And second, it appears that typos don’t often affect numbers used in contracts, at least not in a way that’s newsworthy: the two examples I cite above are the only examples I’ve encountered in 19 years of blogging about misadventures in contract drafting.

By contrast, the downside to using only words is extreme. Whatever authority on English usage you consult, the convention is to use words for small numbers, then switch to digits. If you ignore that convention, instead of saying, for example, 3,577 shares, you end up saying three-thousand five-hundred and seventy-seven shares. Instead of 60 days, you say sixty days. Instead of 45%, you say forty-five percent. Instead of $11,486.32, you say eleven-thousand four-hundred and eighty-six dollars and thirty-two cents.

Considered individually, some of those examples are more annoying than others. Scribendi, a provider of editing and proofreading services, says here, regarding the convention that you start with words then switch to digits, “The reason for this is relatively intuitive. Writing out large numbers not only wastes space but could also be a major distraction to your readers.”

But I suggest that considered cumulatively, adopting the words-only approach would be preposterous, regardless of whether the number is big or small. You’d be forgoing the eye-catching impact of digits for a negligible benefit. I’d rather do words-and-digits instead. It’s just as well that words-only for numbers ain’t happening.

As always, the fix for digit glitches is … proofreading! If you think that’s too much of an imposition compared with inflicting on your readers words-only for numbers, I don’t know what to tell you.

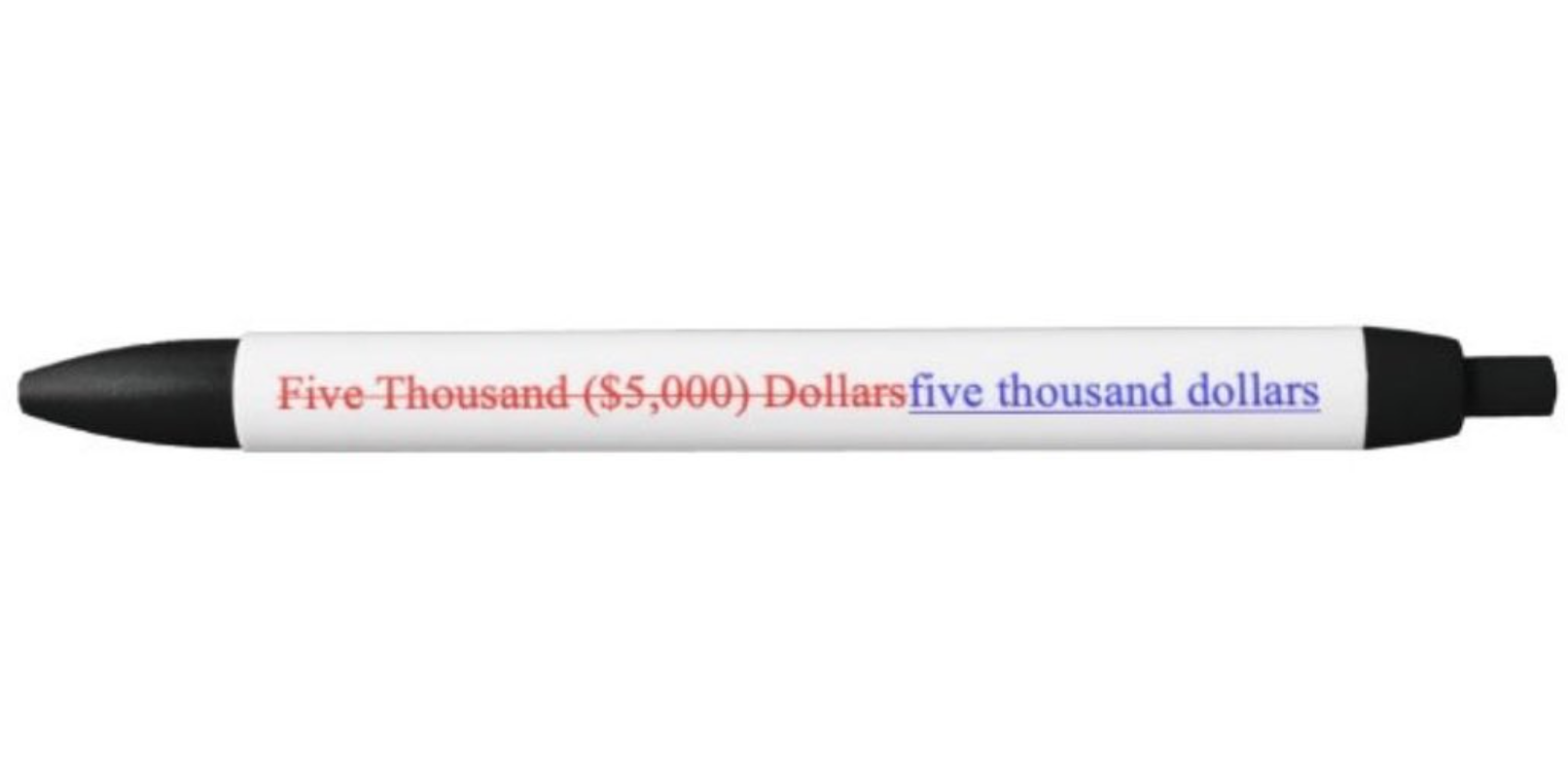

(Regarding the image at the top of this post, it’s by Tom Kretchmar, whose comment to Nick Bullard’s post (here) links here to an image on Instagram that opts for five thousand dollars to replace a strike-through words-and-digits version. But Tom made clear to me separately that he’s not advocating using words only—he’s against using both words and digits but otherwise doesn’t have a preference regarding what convention you should use instead. My thanks to Tom for allowing me to use his image.)

I hate reading numbers written out as words. Massachusetts statutes adopt that convention and it’s maddening: section four hundred thirty-seven A of chapter sixteen and one-half (not a real section but you get the idea). Try reading page after page of that stuff.

Reading this line:

>eleven-thousand four-hundred and eighty-six dollars and thirty-two cents

made me choke on extra hyphens and the extra “and” in “four hundred eighty-six.” So I looked it because if anyone appreciates research, it’s Ken Adams.

https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/3518/american-vs-british-english-meaning-of-one-hundred-and-fifty#3519 long discussion say “hundred AND eighty-six” is BrEng; without the “and” is more typically AmEng.

This source: suggests a mish-mash as a style matter, but there is consistency in the use of hyphens in “eighty-six” and not in “four hundred.”

References to the AP Stylebook and similar style guides in those answers aren’t quite as authoritative as our own respective grade-school teachers, so I suppose I’ll end with these conclusions:

1. Be consistent.

2. Remember that people from a wide range of cultures write things in English: have a little grace when reading (i.e., I know Ken has a substantial amount of English education, and so there you go).

Thanks, Ken!

Thanks Rick! I confess to not having researched expressing bigger numbers in words. (Flagellates self with noodle.)

Regarding the AND, I’ve been dogged my entire life by BrEnglishisms, having done all my secondary and college education in England.

I could include in MSCD6 a section on stating bigger numbers in words, but that would be a little silly, since my recommendation would be that you NOT do so.

I think that the MSCD non-suggestion makes sense. It’s a style guide you’re writing, not a grammar book.

My second link was dropped from my comment:

I just had a lawyer tell me in a very condescending and nasty fashion that it was A REQUIREMENT (and he said it in all capital letters, just like that, A REQUIREMENT) to put both the words AND the numbers in a contract, that he had to fix my form (!!) because I was WRONG (again, spoken in all caps). When I attempted to point out that there are differences of opinion even across commonly used style guides (and before I could direct him to the MSCD), he doubled down on it being A REQUIREMENT. But then again, he apparently attended Ye Olde Colege of Lawe because he also stated vehemently that using the words “IN WITNESS WHEREOF” was also A REQUIREMENT, because the signatures would not be valid without it.

So. There you have it. Bring out your dead. /Rings bell/

Jeepers!