These days I live something of an incrementalist life.

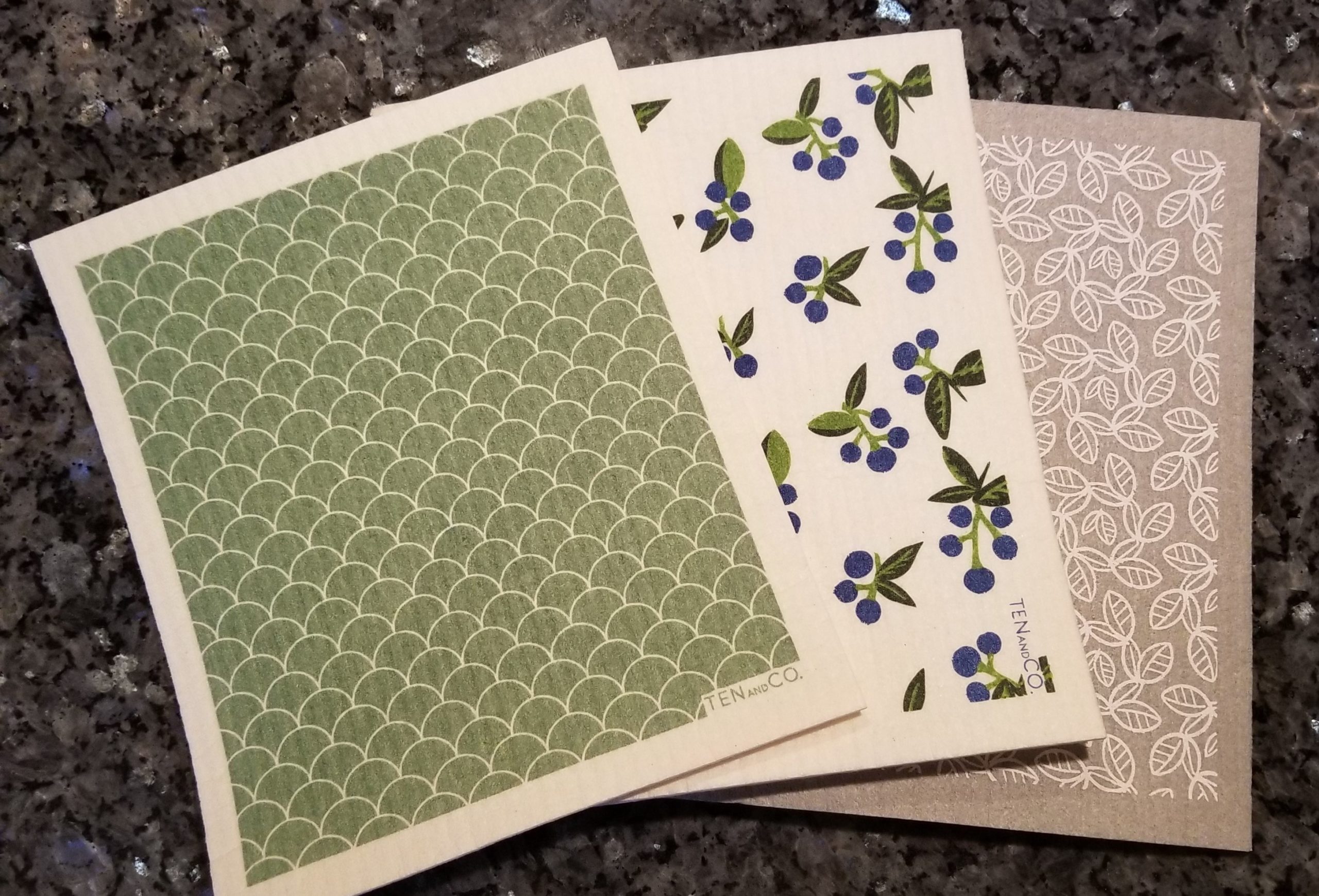

For example, in an overnight switch I now pour oat milk, instead of cow’s milk, on my industrial quantities of granola, but I don’t expect to give up cheese anytime soon. And in an attempt stop using so many paper towels and so much plastic wrap, I currently use sponge cloths from Ten and Co. (that’s them in the photo above) and beeswax wraps from Bees Wrap. On the other hand, I still don’t compost our food waste—my one attempt at composting failed ignominiously.

But I’m no incrementalist when it comes to making contracts clearer. A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting has something to say about pretty much every problematic usage encountered with any frequency in contracts. It offers alternatives, and it recommends you use all of them, whether what’s at stake is simply minor awkwardness or the deal possibly imploding.

Why so absolutist? My position might seem extreme, and extremism can carry with it a whiff of danger and intolerance. (Barry Goldwater’s “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice” comes to mind.) But we’re not talking here about politics, where compromise is essential. Instead, contract drafting is a technical activity. If you don’t do it right, you waste time and money, you hurt your competitiveness, and you risk getting into fights.

But you might ask, do we really have to fix everything? Can’t we just focus on the important stuff? The answer is, No.

Plenty of suboptimal usages don’t themselves add risk and so could be considered just an annoyance. Using the defined term this Agreement. Saying New York law shall govern this agreement instead of governs. I could go on. And on. And on. But such annoyances permeate traditional contract drafting. Considered together, they create a fog that makes it harder to figure out what’s going on. So you risk missing stuff.

Furthermore, that which seems benign might cause problems. MSCD recommend not using the word execute to refer to signing a contract. If you think that seems like pedantic wordsmithing, you would be wrong—this issue featured in a prominent case before the Delaware Chancery Court. (See this 2018 blog post.) And see this recent blog post for an alarmingly subtle fight over a verb structure. Again, I could go on and on. Generally, fights over confusing contract language come as a surprise.

So it’s best to be paranoid—be a student of suboptimal usages, and fix everything. That’s consistent with the approach offered by all usage guides. I have yet to encounter a usage guide that suggests you not sweat the small stuff.

But you have to take the context into account. If you’re reviewing the other side’s draft, your goal isn’t to turn it into a thing of beauty. Instead, limit yourself to what doesn’t reflect the deal as you understand it and what might create confusion. And some practice areas are more averse to change than others. For example, I’d be cautious about using states instead of represents and warrants in your M&A drafts.

Bearing that in mind, I invite you to join me in being absolutist. In the coming months I’ll be rolling out online programs aimed at making that easier. Stay tuned.