[Updated 2:30 p.m. ET to incorporate Vance’s version (see his comment).]

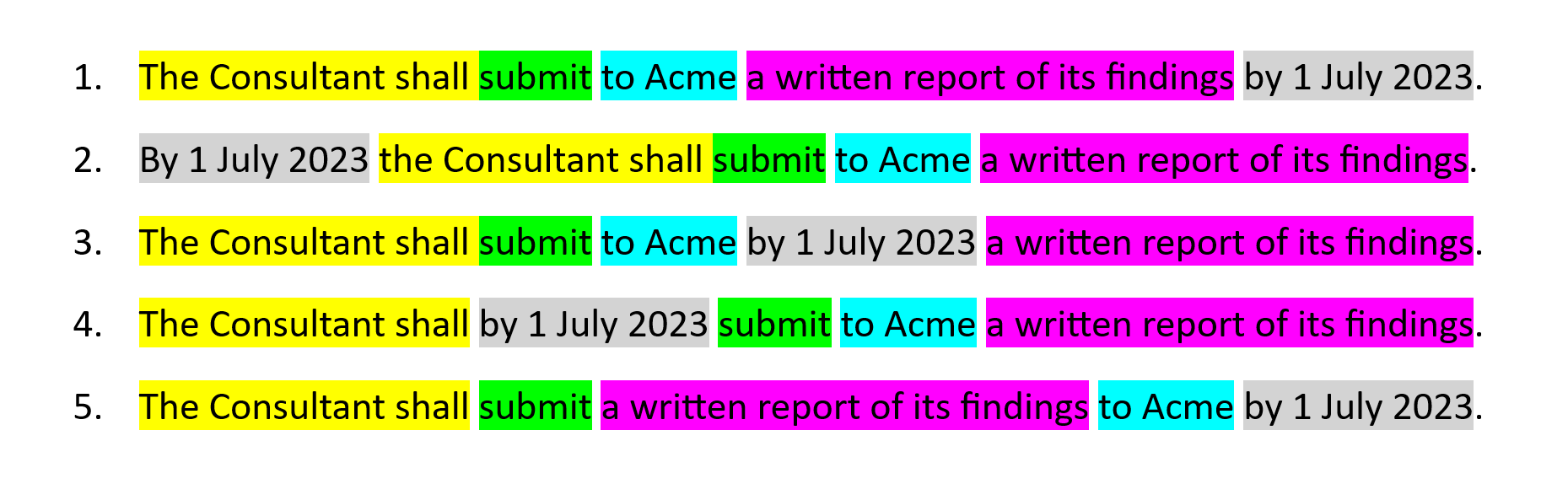

Below are five versions of a sentence, with the only difference being the order in which the components are arranged.

I listed the first four in the order in which I preferred them at the time of posting, from most preferred to least. The fifth is the version proposed by Vance in his comment to this post.

Regarding Vance’s version, the longer the direct object (in this case, a written report of its findings), the more inclined I am to put it after the indirect object (in this case, Acme), one reason being that the indirect object tends to get embroiled in syntactic ambiguity. (I’m afraid I don’t have the time to research the linguistics of this.)

The point of this post is just to remind myself that how to order the parts is just one more issue to consider in writing contracts or anything else.

All of those constructions strike me as stilted. Granted, #1 is the least stilted of the four, but I find the more natural word order to be subject-verb-direct object-indirect object (with limited exceptions for one-word names and pronouns), so I’d say “The Consultant shall submit a written report of its findings to Acme by [can we do this in American?] July 1, 2023.”

Hi Vance. Yes, you’re right, but I’m paranoid about syntactic ambiguity. “A report of its findings to Acme”? So the report concerns stuff the consultant told Acme?

I know that’s outlandish here, but the more complex the direct object, the greater the odds of a miscue or worse.

A deep edge case of potential syntactic ambiguity is where the findings could be produced both before and after the identified date. Then you could be presenting a report of those findings you made before the date. Presumably, there would be more findings later that might be treated differently.

Another advantage of Vance’s formulation is that it avoids the risk (albeit small) of ambiguity around the word “its”. In versions 1-4, couldn’t you argue that the report is of Acme’s findings, not the consultant’s? You could of course fix this with a longer phrase: replacing “its” with “the Consultant’s findings”.

Good point, although in this case the context precludes any confusion.

I’m with Vance; version 5 is the best.

But I see three unrelated issues (off-topic warning!).

1/ Concision. Why not say ‘shall give Acme’? Saves a word (“to”) and swaps a shorter Anglo-Saxon word (“give”) for a longer Latinate one (“submit”) in the process.

2/ Use of a period of time to describe a point in time. Unless ‘by’ is defined or made the subject of an internal rule of interpretation, the sentence leaves the deadline unspecified. Is it (a) the start of 1 July 2023; (b) the start of business on 1 July 2023; (c) noon on 1 July 2023; (d) the close of business on 1 July 2023, (e) that date’s final midnight, or (f) some other of that date’s infinity of points in time?

3/ Transmisia. What of the consultant’s pronouns? Michael Argy is on the right track for other reasons: ‘replac[e] “its” with “the Consultant’s findings”‘.

So there’s room for further versions. By the way, if anyone ever accuses you of hypertechnicality, tell them that paying close attention is a way of showing love.

–Wright

Of course it’s off-topic! :-) At some point I’ll respond to your points.

I tend to agree with Vance that #5 is the most natural sounding. Natural because that’s the structure that you’d use use during face-to-face conversation. It works when you’re speaking because you can immediately clarify syntactic ambiguities with the speaker. But that’s generally not possible when you’re confronted with a written contact and the author is absent.

I’ve confronted the issue that Ken identified in many of the contracts that I draft. I find that I use construction #1 quite a lot (and always for enumeration and computation). I explicitly avoid #5 because of the syntactic problems. To the point of giving #5 wide berth: while I might think that my construction is ok, a lay reader might find a syntactic issue that I overlooked.

There’s another reason to prefer #1 other than syntactic ambiguity–making it easy for your reader to comprehend what is being said. When the direct object gets longer (10 plus words), it gets harder for the reader to understand what is being said if the indirect object appears after a lengthy direct object.

Number 2 places the due date (July 1) closest to the actor (Consultant). Making it clear that “Consultant must act by this date.”

In that way, Number 2 avoids the potential miscue of Number 1: “Consultant must present findings by July 1” — which could mean the consultant’s *findings* up to that date. Not the *submission* by that date.

To reduce/eliminate ambiguity, shouldn’t the [Due_Date] be closest to the [Actor] + [Action]?

#2 is best as applied — i.e., if the purpose of all this work is to prevent problems in the real world, #2 works best. This is how it would be structured in a high-reliability critical field where failure is punishable by catastrophes.

It best matches the playscript format and puts the critical deadline for action in pole position, and then gives who does what in the simplest way.

Commas? Commas? We don’t need no stinkin’ commas!

The Consultant shall submit to Acme, by 1 July 2023, a written report of its findings.