Today someone asked me this in an email message:

Are you exploring training AI to incorporate A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting for proofreading contracts? I could see value in a plug-in that incorporates (in track changes) relevant proposed modifications after “learning” the contents of MSCD and applying it to all or part of a contract.

This isn’t the first time I’ve encountered this idea. In this 1 March 2023 blog post, Casey Flaherty says, “And maybe, someday, an LLM will be used to apply the sixth edition of Ken’s MSCD to every contract destined for EDGAR.”

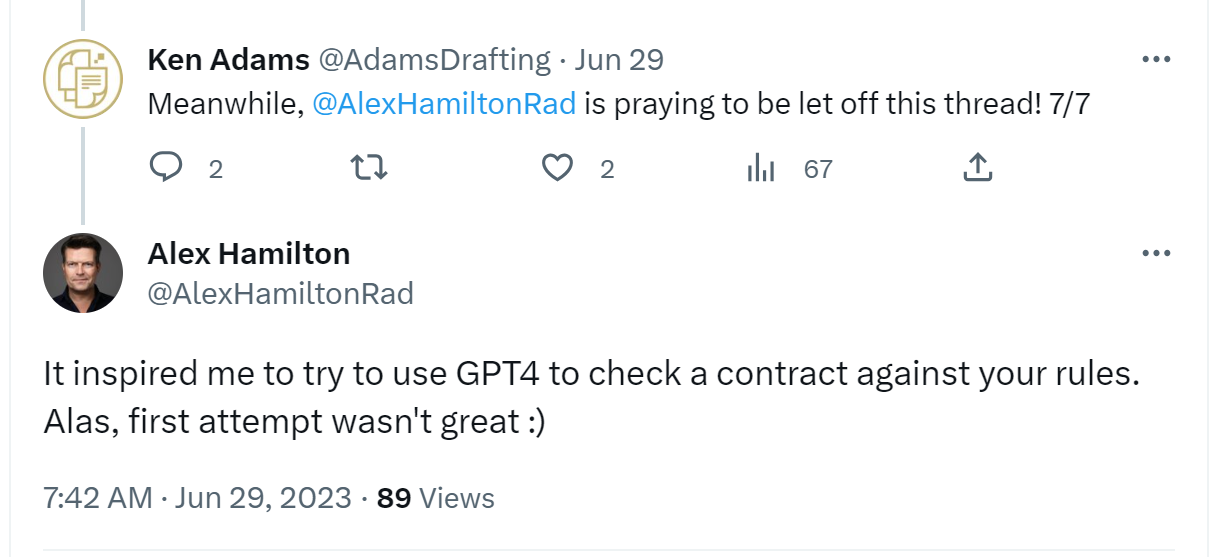

And there’s this 29 June 2023 tweet by Alex Hamilton:

If Casey and Alex both casually air an idea, I’d be silly not to consider it.

I don’t know that one needs to invoke artificial intelligence for systems that check whether a document complies with a set of guidelines. After all, WordRake and Grammarly would seem to be editing software rather than AI. But one could conceivably feed MSCD to a large language model (LLM). Doing so would in theory spare you the kind of work that has gone into WordRake and Grammarly.

Whether you use a WordRake/Grammarly approach or use an LLM, the question is whether the task is feasible. For three reasons, I suggest it’s unlikely to work out well.

First, the dysfunction of mainstream contract language means that often you don’t know what a given formulation is trying to accomplish. Take for example a limitation-of-liability provision that excludes consequential damages. It’s not clear what the drafter had in mind, to the extent they had anything in mind other than copy-and-pasting. So a simple substitution of the WordRake/Grammarly sort isn’t an option. Instead, the best one could do is point the user to the MSCD discussion of consequential damages (see this 2022 blog post). I could offer you many other such examples.

Second, the dysfunction of mainstream contract language doesn’t just consist of single-vehicle accidents. Instead, you routinely get multiple-vehicle pile-ups, such that switching out suboptimal usage No. 1 for some standard alternative doesn’t make sense because of how suboptimal usage No. 1 interacts with suboptimal usage No. 2, which in turn interacts with suboptimal usage No. 3. Often I end up discarding the original and instead say the same thing in an entirely different way. Currently, I don’t think it would be realistic to expect any kind of technology to accomplish that.

And third, the dysfunction tends to be so dense that whatever your technology, from beginning to end it would have to hack through the jungle with a machete. As I jokingly suggested to Alex in our Twitter exchange, any machine faced with such a task would emit sparks and blue smoke. (For an example of that density, go to this 2021 blog post for (1) six extracts of the Salesforce master agreement that I annotated to describe the drafting shortcomings and (2) my reworked version of each extract.)

So it would seem unrealistic to expect technology to digest MSCD and present you with a suitably reworked draft of any contract you feed it. But I can think of two alternatives.

One would be to use technology not to offer a rewrite, but instead to offer explanatory annotations, leaving it to the user to decide what kind of fixes to apply. That’s what LegalSifter offers with their contract-review product; I’ve spend much of the past five years helping them with that.

But fixing mainstream contract drafting is a nuisance. You might want to consider instead a fresh start, but not of the sort that requires random copy-and-pasting or a protracted drafting-by-committee nightmare. The options for such a fresh start are currently slim to nonexistent. Let’s see whether I can come up with something.

All that said, I remain open to other possibilities.

Ken:

Applying a large language model to enforce MSCD rules would be a technical problem. LLMs require lots and lots of exemplars. They then predict what text ought to be based on examples. If there were lots and lots of exemplars of dratting according to MSCD rules, you probably would not have written MSCD. Rather, agreements oriented to MSCD are still the exception rather than the rule.

So, in any big set of contracts, you’d need to separate wheat from chaff. The first tule I’d use in doing so is to only keep form agreements, not negotiated agreements. My rationale is that, if 1 out of 100 contract drafter-negotiators would use MSCD, then only 1 out of 10,000 random pairs of counter-parties would both use MSCD as their baseline. With forms, only one side is involved, so you get the 1 out of 100 ratio. But I don’t know where you’d find loads of forms. For final agreements, you can look to EDGAR. But then you are trying to find the 1 in 10,000 that conforms to MSCD’s recommendations.

Maybe you could use some of the structures that MSCD recommends never to use as the signal to exclude a specific agreement or form from the full set. Like “witnesseth” is a dead give-away. And it seems like, if you are creating the logic that would look for good forms, you could just use that as software to make rule-based suggestions directly!

Chris

Hi Chris. This post assumes that one feeds an LLM the text of MSCD. That’s very different from what you’re contemplating, namely training AI on a stash of MSCD-compliant contracts. That might be feasible down the road, but for the foreseeable future, the only way to get MSCD-compliant contracts will be by building them painstakingly from scratch or by using a library of automated templates. And if such a library exists, and it’s comprehensive enough, one wouldn’t need AI.

Ken:

I don’t doubt my own ignorance in the field of AI, but I’ve never experienced an AI mode that would be built that way. Every one that I’ve worked with implicitly derived rules from exemplars. (Yes, for the technical, I know they aren’t really rules; they are vectors and blah blah blah. Work with me here.) LLMs in particular, essentially predict what word should come next. From that perspective the useful part of MCSD is the examples, coded to whether they are recommended or not. The rest of MCSD would mislead the LLM into providing words that analyze words and phrases, refer to grammar, and use key cases as examples.

Chris

Hi Chris. You’re probably right. I was just riffing off of the scenario I was offered. It might be utterly unrealistic. At some point I’ll look into it further.