These days I don’t write much about legaltech for contracts. There’s way too much of it. And I don’t do deals, so I’m not in much of a position to put such products through their paces. But I’m making an exception with this Q&A with Steven Gullion, of CrossCheck.

CrossCheck looks for technical glitches that can afflict use of defined terms and cross-references, among other things. Looking for such glitches unaided is a soul-crushing time-suck, but such glitches are a nuisance, and they can cause real problems. That puts those who work with contracts between a rock and a hard place.

This kind of work is conducive to automation, but somehow no product has really caught on in the broader market. If you’re expending brain cells checking your defined terms and cross-references, or if you break out in a cold sweat at the thought of doing so, do yourselves a favor and try CrossCheck.

***

Ken: Tell us about your background and the inspiration behind CrossCheck.

Steve: After graduating from law school at the University of Virginia, I joined a boutique corporate and securities firm in Houston. As a first-year lawyer, I spent a lot of time reviewing contracts, looking for errors related to defined terms, outline structure, and cross-references. It’s tedious work, and it’s easy to make mistakes. It made me wonder, “Is this why I went to law school?”

I had studied computer programming in college and I realized that a lot of the review work I was doing could be made easier, faster, and more accurate by using a computer. CrossCheck is an add-in for Microsoft Word that proofreads contracts for precisely the types of mistakes that I looked for as an associate.

I like to say that CrossCheck is like a superhero whose superpowers are reading really fast and being really, really picky.

Ken: What does CrossCheck do, exactly?

Steve: First, CrossCheck parses the document (totally within Microsoft Word) and creates a fully detailed outline, including all subclauses and enumerations. (We expect that most CrossCheck users will use it to review contracts, but it can be used on any document that has a highly outlined structure and that contains cross-references or uses defined terms.) The outline is displayed in the CrossCheck panel (which sits to the right of the document text); clicking on any outline item scrolls the document to that section. This is very useful when you’re trying to find, say, section 15.13(a)(i)(x)(II)(3).

Second, CrossCheck compiles a list of all defined terms. This list too is available in the CrossCheck panel, so the user can quickly move to the definition of a term and each place the term is used.

And third, lists are made of all the cross-references and all undefined terms. Like the other lists, you can use these lists to navigate through the text.

As part of that process, any issues are flagged. All of this only takes a few seconds, even for a 200-page document. The user can choose between consulting the lists or taking a “Guided Review,” which walks through the primary issues one by one, with detailed explanations.

The user can then make corrections, generate a report to email to others, or insert comments directly into the document with a click (handy when reviewing the other side’s draft).

Ken: Give us some examples of the kinds of mistakes CrossCheck might find.

Steve: We’ve analyzed thousands of contracts with CrossCheck and the most common errors that we see are incorrect cross-references. For example:

“Arbiter” has the meaning ascribed to such term in Section 10.9(d).

In the contract from which this sentence was taken, there is no section 10.9(d). In fact in that contract there are 88 incorrect cross-references—it appears that an article was deleted from the middle of the contract but no one thought to adjust the cross-references accordingly.

When CrossCheck spots an error like this one, it tells the user that the section doesn’t exist and says where the term is in fact defined, if it finds a definition.

Here’s another example, from an index of definitions:

Incumbent Investor Director 6.11

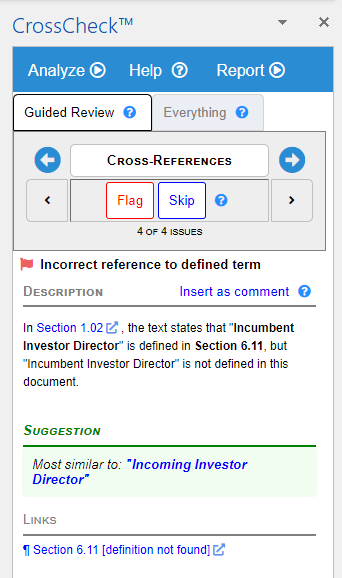

The defined term Incumbent Investor Director isn’t defined in section 6.11 or anywhere else. Guided Review flags the issue like this:

CrossCheck notes (under “Suggestion”) that Incoming [rather than Incumbent] Investor Director is a defined term; perhaps that was what the drafter had intended. Guided Review also provides a link to section 6.11, letting the user jump directly to the definition of Incoming Investor Director.

Another common cross-reference issue is misuse of the word this. If a sentence says this Section 7.2 but that sentence is in section 8.3, did the drafter intend to refer to section 7.2 and included this by mistake, or did they intend to refer to section 8.3 and got the number wrong? It’s impossible for CrossCheck to know which is correct, but it identifies the problem.

CrossCheck also looks for terms that are defined more than once, terms that are never defined, terms that are defined but never used, outlines that have missing or duplicate section numbers, a table of contents that doesn’t match the document, and more.

CrossCheck looks for problematic dates. For example, February 29 in a year that isn’t a leap year. Years before 1900 and after 2200. And a day of the week that doesn’t match the date, as in Sunday, January 16, 2023—it should be Monday.

And CrossCheck spots inconsistencies in numbers expressed using both words and digits. For example, CrossCheck found this sentence in another EDGAR contract:

C******** shall pay, or cause to be paid, to V****: (i) a fee equal to Four Million Five Hundred Dollars ($4,500,000).

The odds are that the digits reflect what the drafter intended to say. This kind of error doesn’t occur often, but it’s certainly one you would want to have flagged.

Ken: By the way, regarding that contract with 88 incorrect cross-references, it would seem that the drafter hadn’t used coded cross-references—if they had, the cross-references would have adjusted automatically when an article was deleted. Do you have a sense of what proportion of drafters don’t use automated cross-references?

Steve: Great question. We don’t have access to the original Word documents (assuming Word was used in the first place), so it’s impossible to say with certainty. But based on how often we see cross-reference errors, I’d say that very few documents are coded, or, if they are, they aren’t completely coded. It’s common to see issues with 1% to 5% of cross-references.

Some of these issues, such as references to nonexistent sections, could be avoided by coding. For some other issues, coding wouldn’t help. For example, in section 6.4(b) of the Microsoft–Activision merger agreement, the Romanette hierarchy—beginning with (i)—occurs twice, and the contract contains a cross-reference to section 6.4(b)(i). It’s not clear what is being referred to. CrossCheck identifies this kind of confusion.

Ken: I gather you assign documents a score.

Steve: Yes, a score between 0 and 100—a higher score means fewer glitches. The score is just meant to be a quick and dirty measure of how “clean” a document is. Most of the documents we see on EDGAR score in the high 90s, but those are finished documents that have gone through multiple rounds of review. The score is more useful in the drafting phase. If you’re about to distribute a revision and you get a score in the 70s, you might want to give it another look.

Ken: People who work with contracts are accustomed to doing this type of review manually. Is software really necessary?

Steve: Anyone who works with contracts knows that contracts can become very complicated, but when you see the metrics, it’s a little shocking.

We analyzed 2,023 arbitrarily chosen merger documents on EDGAR. They contained an average of 152 defined terms, 766 outline items, 283 cross-references, and 3,897 references to defined terms.

The most complex document contained 528 defined terms, 2,522 outline items, and 762 cross-references. The defined terms were referred to 12,103 times. Checking all those details for each new draft would be burdensome and time-consuming, and mistakes are inevitable.

Given how many things could go wrong, it’s a testament to the legal teams involved that CrossCheck only identified, on average, 45 issues per document.

Ken: Lawyers can be very reluctant to use software in their work. Why do you think this is?

Steve: For the most part, lawyers don’t want to be programmers, and they resist using software that tries to change the way they work. My first product was a document-assembly engine, and I learned quickly that most lawyers had no interest in spending the time required to automate their documents.

CrossCheck is easy. It doesn’t take over; it doesn’t require any complicated setup. It works with any conventional contract, if it’s a Word document. CrossCheck just helps lawyers and other reviewers do what they already do.

Ken: Some tools like this one report too many “issues” that aren’t real problems (aka false positives). How does CrossCheck handle this?

Steve: Our goal is to report every valid issue and only valid issues, but there are times when an issue might be important to one reviewer but not to another. As we say on our website, “How picky are you?”

For example, CrossCheck can indicate when a defined term appears in a contract before the term is defined (or at least listed in an index of definitions). A lawyer we know got comments from a member of her board of directors pointing out this very issue in an annual report she had drafted. With CrossCheck, she was able to quickly make the necessary fixes.

But “false positives” do happen, most often in the list of undefined terms. These are uncommon words and phrases that are capitalized but not defined. Obviously, lots of things are capitalized that don’t need to be defined, such as names of people and places, dates, and titles of legislation. CrossCheck uses a number of strategies to identify such common terms and ignore them, and we continue working to reduce the number of false positives of this type.

Ken: Regarding flagging when a defined term is used in a contract before the term is defined, is that an option you can select? If so, is it selected by default? I wouldn’t want to flag that. In contracts drafted consistent with my recommendations in A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting, such instances would be commonplace, because you would put in a definition section toward the back of the contract those defined terms with a meaning that is largely or entirely clear.

Steve: We recognize that for many, using a defined term before you define it won’t be an issue, so we take care to keep it in the background. It’s not part of the Guided Review or the main report. There’s an entirely separate report just for this item that the user can choose to run, so the information is there if needed, but otherwise it’s not intrusive. But we plan to make it optional whether you look for this and some other minor issues.

Ken: This isn’t your first product of this sort. I’ve long wondered why no defined-term-checking product has gained traction in the market. Why do you think that is? It’s such an obvious need.

Steve: I wish I knew the answer to that! I think the answer is complicated, but a big part of it is a perception that software is complicated, takes a long time to learn, and doesn’t always deliver on its promises. Our goal with CrossCheck is to keep it simple to use without dumbing down what it can do.

Ken: How would you respond to someone who asks you, “Can’t ChatGPT do these sorts of things?” And more generally, does your technology involve artificial intelligence?

Steve: We’ve done some informal testing with ChatGPT. For example, we asked it to identify all the defined terms in a confidentiality agreement. It returned a list of capitalized words, which included the defined terms but also a lot of other things, so it was superficially impressive but not all that accurate.

CrossCheck doesn’t use AI. I realize that AI is currently all the rage, but it’s not a cure-all. AI applies automation to the most nuanced forms of expression. By comparison, the issues CrossCheck looks for manifest themselves in a few set ways. For the problems we’re addressing, we don’t need AI and all its associated uncertainty.

Ken: What does the competition look like?

Steve: There are other products that do defined-term checking, but I’m not aware of any other product that can check outline structure and cross-references as thoroughly as CrossCheck.

Ken: How has CrossCheck been tested?

Steve: Most of the testing has been done on public documents filed with EDGAR. We’ve analyzed thousands of documents, many of which were over a hundred pages long, and we continue to analyze new documents every week.

Ken: Your website says that CrossCheck will be free of charge until 30 June 2023. Why such a long free-trial period?

Steve: We want to give users a chance to really become familiar with CrossCheck and see how much it helps. We don’t think a one-week or even one-month period is enough. Also, we’re eager for feedback from a wide variety of users so we can continue to refine CrossCheck and provide the best user experience possible.

Ken: How will CrossCheck be priced after the trial period?

Steve: We’ll charge a monthly subscription fee that will be comparable to what is charged for similar products.

Ken: What about security? Does CrossCheck require an Internet connection?

Steve: CrossCheck does connect to the Internet from within Word. Authentication (logging in) is done using Microsoft’s single-sign-on service, so the user doesn’t need to create a separate login name or password with CrossCheck.

Because CrossCheck is an “Office.js” application, it’s loaded from our Internet servers each time it’s run. But all analysis is done within Microsoft Word. No document text is ever uploaded to our servers or otherwise sent to the cloud from the add-in.

We also have a web version of the application at https://www.crosscheck.legal that allows a user to submit a document to the cloud for online processing. This is done via a secure connection, and we don’t store the document permanently on our servers.

Ken: What operating system is required to use CrossCheck?

Steve: CrossCheck works on Word for Windows, Word for Mac, and Word Online (browser-based).

Ken: Where can we get more information?

Steve: At https://www.crosscheck.legal. And check out the CrossCheck Challenge while you’re there—we ask ten multiple-choice questions about two less-than-perfect contract extracts.