One of the joys of scholarship is that it offers plenty of opportunity for you to be a doofus. I’ve taken advantage of that over the years. It goes with the territory: if your scholarship is worth anything, it will venture into the unknown (unknown to you, at least), and the unknown is where you stumble.

My most recent opportunity to be a doofus occurred last week. The subject was time zones.

For How Many Hours Will It Be Day X?

In this 2022 blog post I wrote about how time zones relate to the date of the contract. Then earlier this year I saw this LinkedIn post by Justin Turman, founder of Automate Office Work and resident of Amsterdam, lucky fellow. Here’s what Justin says in his post:

Legal contract pro tip: If timing really matters for you, consider adding a time zone to important dates. If you only specify a date with no time zone, because of how time zones wrap around the earth your specified day could actually take 48 hours to progress around the earth. You might think “Aha, the contract is now expired” when actually the sun still has another 24 hours because of how the international dateline works.

Last week I dared to suggest to Justin that the figure of 48 hours might not make sense. He gently set me straight. Here’s my take on what he explained to me:

If a contract says it will terminate on a given day (which I’ll call “Day X”), for how many hours will it be Day X somewhere in the world? The answer is, 50 hours, if you include all official time zones, which run from UTC+14 (covering some islands in the Pacific) through UTC−12 (covering other islands in the Pacific). (“UTC” means Coordinated Universal Time, the successor to Greenwich Mean Time.)

The first time zone to experience 00.00 (midnight at the beginning of Day X) is UTC+14. At that time, it’s 10.00 UTC on the day before Day X.

The last time zone to experience 24.00 (midnight at the end of Day X) is UTC−12. At that time, it’s noon UTC on the day after Day X.

You get the number of hours it’s Day X somewhere in the world by adding to the 24 hours of Day X in the UTC time zone (1) the extra 14 hours of Day X in UTC+14 and (2) the extra 12 hours of Day X in UTC−12: 24 + 14 + 12 = 50.

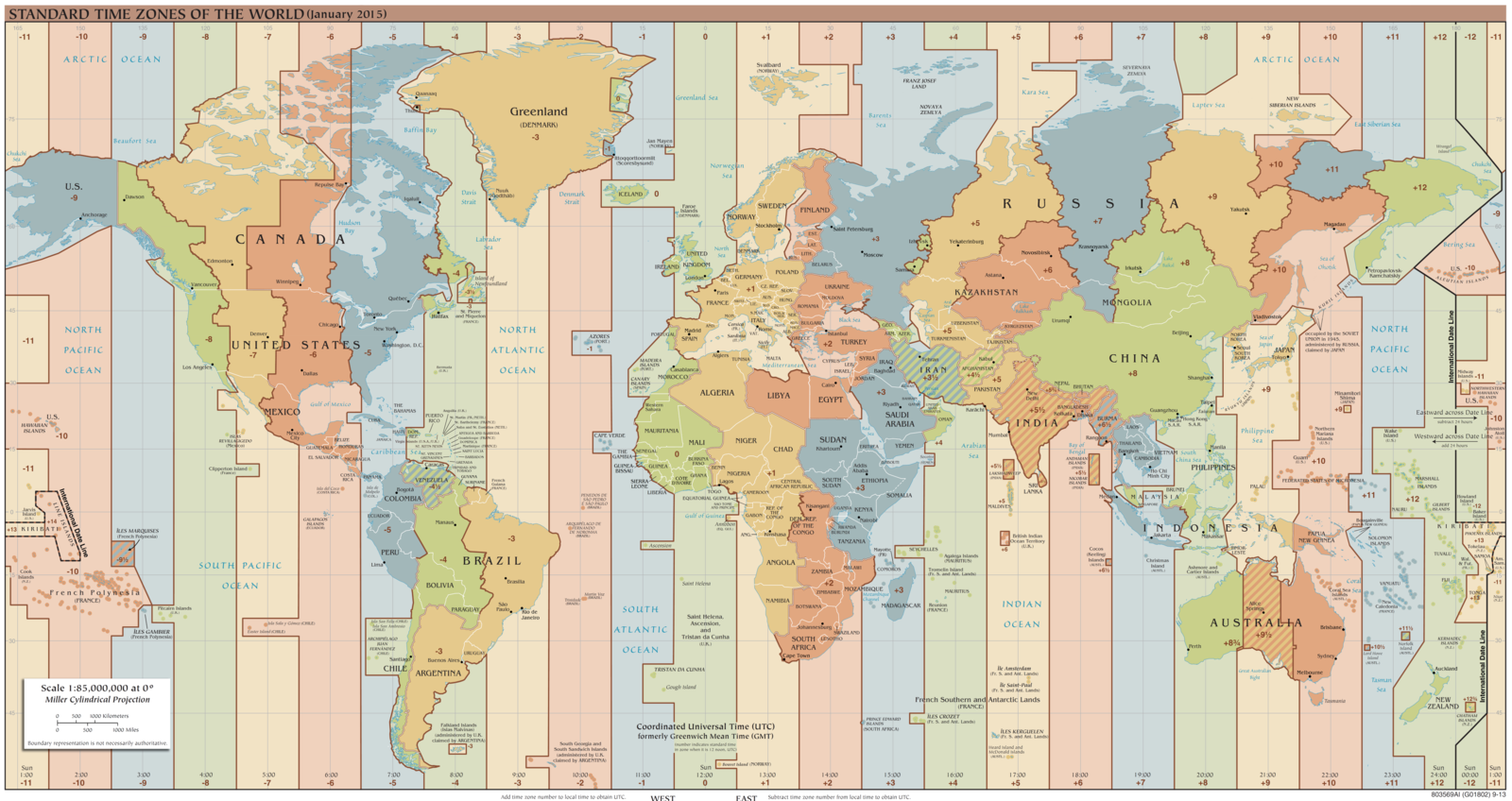

This is just my way of thinking through this issue; Justin’s thought process is a little different, although it leads to the same result. You might want to start by pondering a map of time zones, like the one at the top of this post.

Two Kinds of Dispute

The logic that gets you to 50 hours is relevant only if a reference to time might apply at any point in a given day. That’s the case only if a contract refers to a date without stating a time of day, as in Acme shall deliver the Widgets on 15 April 2028. Referring to just a date leaves it uncertain when in the 24 hours of that day that point in time occurs.

Because most of us aren’t doing deals between, say, a business on Baker Island (UTC-12) and a business based in the Republic of Kiribati (UTC+14), let’s use an example that’s more likely to occur. If a deal is between a company based in California (UTC-7) and one based in Melbourne, Australia (UTC+10), a fight over what Acme shall deliver the Widgets on 15 April 2028 means might involve not only the 24 hours of that day but also the question of which time zone applies. The latter factor would bring into play (1) the extra 7 hours of that day in UTC+7 and (2) the extra 10 hours of that day in UTC-12, so the number of hours being fought over would be 24 + 7 + 10, namely 41.

If a contract refers to a time of day, the fight would no longer involve the 24 hours of that day. Instead, the only issue would be which time zone applies. In the case of our California-Melbourne example, the spread would be 17 hours. That’s less than 50 hours, but one could dream up scenarios leading to a fight over those 17 hours.

Avoiding Fights

How do you avoid either kind of fight? Use a time of day, not just a date, when stating points in time. And use this internal rule of interpretation: All references to time are based on the time in [location]. It’s one of the few internal rules that’s worth a damn.

Apparently, ChatGPT suggests that instead you say in contracts that the time zone that applies is the time zone where the contract is performed. If you follow that logic, you should also not bother saying what the governing law is and instead let it be determined based on where the contract is performed. In both contexts, if you follow that approach you might be dismayed to find yourself having to become acquainted with the considerable caselaw on how to determine where a contract is performed.

It’s standard to include a governing-law provision in contracts, even though there are limited circumstances in which a governing-law provision might not be enforced. Similarly, it would make sense to say that references to time are based on the time in a specified location, bearing in mind that if the specified location has no connection with the transaction, a court might elect to refer instead to the time in some other location.

So no thanks, ChatGPT.

For more fun with references to time, see chapter 10 of A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting.

(I’m using the image at the top of this post under a Creative Commons license. The image is on Wikimedia Commons, here.)

“Scholarship offers many chances to be a doofus.” Should be my motto.

“How many hours are in Day X?” is a special case of the common failure to describe a period from startpoint to endpoint.

When you want to describe a point, give the point’s time zone. When you want to describe a period, give the time zone of both the startpoint and the endpoint, either on site or in an internal rule of construction.

Don’t put down internal rules of construction! They are a nifty way to concisely clear the brush away on many recurrent matters, including “including,” gender, number, and or.

ChatGPT is such a mixed bag! It’s like the girl with a curl: when good, very good — when bad, horrid. Without great care you may wind up with a mix of the best parts of mother’s apple pie and mud pies.

I sometimes get diametrically opposed long answers on the same question asked weeks apart! Careful out there!

On the question presented, I don’t know whether academia or legalworld is to blame, but the crooked timber of humanity inhabits both.

I still have hope of getting rid of nitcaps on defined terms. Success would take “agreement” along the way.