I’m blessed with idiot-savant semantic acuity but cursed by a lack of any training in grammar or linguistics. That makes for an awkward combination: I recognize when something is going on in a sentence, then I hit the books and, if necessary, go for help. (See this post about my ambiguity sensei, Rodney Huddleston.)

That played out yesterday. I made up the following sentence to showcase a phenomenon I’ve long recognized:

I feel uneasy when I see children who eat pizza, and children who eat pasta, without wearing a bib.

The offsetting commas serve to suggest that what follows the second comma modifies not only what comes immediately before it but also what comes before the first comma.

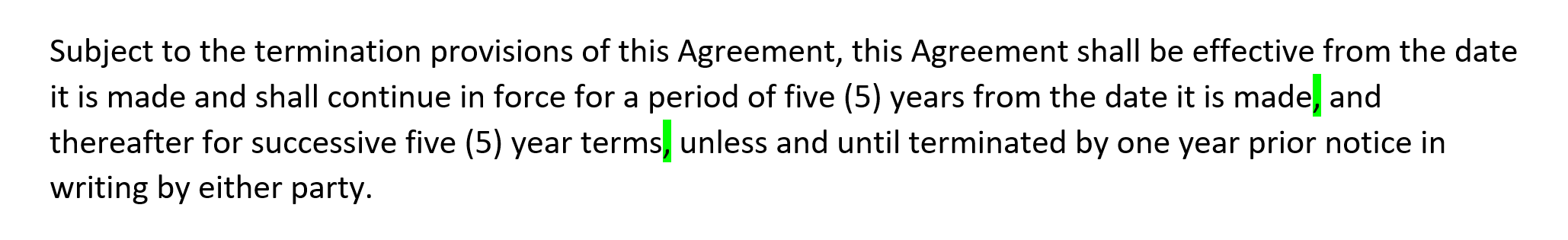

This structure also features in contract disputes. Consider the sentence at issue in the so-called “case of the million-dollar comma” (a dispute between two Canadian cable companies that I describe less than comprehensively in this 2007 article):

The highlighted commas arguably serve the same function as the commas in the previous example.

This has seemed obvious to me, but this structure isn’t mentioned in, for example, Garner’s Modern English Usage, and I wasn’t able to find it in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language either. So I asked Neal Goldfarb, a lawyer who does have linguistics expertise, what this phenomenon is called and where I can find out more about it. “Delimiting commas,” he said, and he assured me that CGEL does discuss it.

Sure enough, there it is, a single paragraph on page 1746. It offers the following examples:

i. The students, and indeed the staff too, opposed all these changes.

ii. She laughed, and laughed again.

iii. He seemed to be both attracted to, and overawed by, the new lodger.

It then says this:

Constituents introduced by coordinators

The effect in [i] is to present the underlined NP as a parenthetical addition rather than as an element on a par with the preceding element in terms of information packaging: we treat this too as a kind of supplementation rather than genuine coordination. In [ii] the second VP is clause-final, so it is not immediately obvious that the comma is delimiting; this becomes apparent, however, when we add a complement: She laughed, and laughed again, at the antics of the little man. Example [iii] belongs to the delayed right constituent construction (Ch. 15, §4.4); the commas, though optional, help show that the new lodger is understood as complement not only of by but also of to.

Ah, finally! But what CGEL doesn’t offer was a catchy name for this phenomenon. I propose we use the label “delimiting commas in coordination.” You’re welcome.

Why is this topic worth a blog post? Because in a world where writers misuse commas and judges don’t understand commas, you’re asking for trouble if you use delimiting commas in coordination. It’s too easy for the reader to ignore the offsetting commas when considering how far back up a sentence a closing modifier reaches.

That’s why in referring to the sentence at issue in “the case of the million-dollar comma” I say that the delimiting commas “arguably” suggest that what follows the second comma modifies not only what comes immediately before it but also what comes before the first comma. Neither the parties to the contract nor the government agency charged with handling this dispute considered the possibility that this sentence features delimiting commas in coordination. Instead, the fight was over whether you could terminate with one year’s notice during the initial five-year term.

And someone concerned about the meaning of the example at the top of this post might disregard the delimiting commas and instead worry about whether I’m anxious about any children eating pizza or just those who aren’t wearing a bib.

So now that I’ve identified this phenomenon, I’m taking it away from you and putting it in a locked display cabinet in the library. If something is at stake, as is generally the case in contracts, don’t rely on delimiting commas in coordination. The example at the top of this post? If we pretend that a lot is riding on it in a contract, and if I permit myself to give free rein to my paranoia about ambiguity associated with or, here’s how I’d reword it:

I feel uneasy when I see children who eat pizza without wearing a bib, and I feel uneasy when I see children who eat pasta without wearing a bib.

Yes, that’s kind of sad. Welcome to contracts. (And it applies equally to statutes.)

(Why am I writing this post now? Because delimiting commas in coordination feature in language at issue in a recent court opinion; when I write about that opinion, I want to be able to cite this post. Stay tuned.)

***

(Hey, while you’re here, check out my new online course, Drafting Clearer Contracts: Masterclass.)

“I feel uneasy when I see children who eat pizza, and children who eat pasta, without wearing a bib.”

You should wear a bib next time. I don’t want you to feel uneasy.

:)

jfc I didn’t even think of that ambiguity.

It clearer to put things in lists?

I feel uneasy when I see a children who are not wearing a bib while they are eating any of the following:

1. Pizza; and/or

2. Pasta

It could be read that I only feel uneasy if I see 2 or more ‘children’ doing this, but is silent on how I feel if there is only 1 child doing it.

Therefore this may be better

I feel uneasy when I see any child who is not wearing a bib while he/she is eating any of the following:

1. Pizza; and/or

2. Pasta

We are sad buggers!

Yes, tabulation can help. It’s one of several workarounds.

And goodness, yes, the singular-or-plural thing rears its head! I dreamed up that example as an illustration, and now you and others are demonstrating how one’s perspective has to change drastically when one is dealing with contract language.

Ken:

In this kind of situation, I often see a lawyer who is at least a little aware of the ambiguity stick in a parenthetical like “without (in either case) wearing bibs.”

Note that using “either pizza or pasta” does not eliminate the ambiguity sufficiently, since the “without wearing bibs” could still modify both elements or the final element.

Chris

I just saw this; I’ll give it some thought.