Yesterday ContractsProf Blog published this guest post by Tina Stark. It serves as a reminder that drafters should distinguish sale of a company from a shareholder’s selling shares. It also serves as a reminder that there are different ways to sell a company.

Here’s the gist of it, from Tina’s post:

In Buckingham v. Buckingham, 14335 314297/11, NYLJ at *1 (App. Div., 1st, Decided March 19, 2015), a well-known matrimonial lawyer botched the drafting of a prenuptial agreement. As drafted, the relevant provision stated that if the husband sold “MS or any of its subsidiaries or related companies,” he was obligated to pay the wife a share of the proceeds. But the provision did not address the consequences of the husband’s sale of any shares he owned in those businesses. Stated differently, the agreement gave the wife the right to proceeds from asset sales, but was silent about the right to proceeds from stock sales.

The couple married; time passed; and the marriage failed. Along the way, the husband sold shares of his business and the ex-wife wanted her share of the proceeds: about $950,000. The husband and the courts said “no.” The court reasoned that the relevant language created a condition to the husband’s obligation to pay sale proceeds to his ex-wife, but that language encompassed only asset sales.

But since we’re in the marketplace of ideas, allow me to offer a slightly different analysis:

Whenever you’re dealing with disposition of a company, you have to bear in mind that there are three ways of accomplishing that:

- Sale of shares

- Sale of assets

- Merger

The provision at issue in this dispute arguably encompasses not just asset sales, as Tina suggests, but instead all three of those alternatives. In fact, the court never mentions asset sales.

It’s relevant that although Tina suggests that the relevant provision is in the active voice, with the husband as the subject, that’s not the case. Instead, it’s in the passive voice, with no by-agent: “… if MS or any of its subsidiaries or related companies are sold ….” That would encompass sale of all the shares of MS, and it could be interpreted as referring, in a colloquial way, to any form of disposition, including an asset sale or merger.

The husband owned a majority (55.83%) of MS shares rather than all the shares. It follows that if the provision had been phrased in the active voice, with the husband as the subject, it couldn’t be interpreted as referring to sale of MS by sale of all MS shares, including those not owned by the husband. It would also be harder to argue that it applies to an asset sale or merger.

But those nuances don’t affect that the wife’s lawyer messed up by not having the provision cover individual sales by the husband.

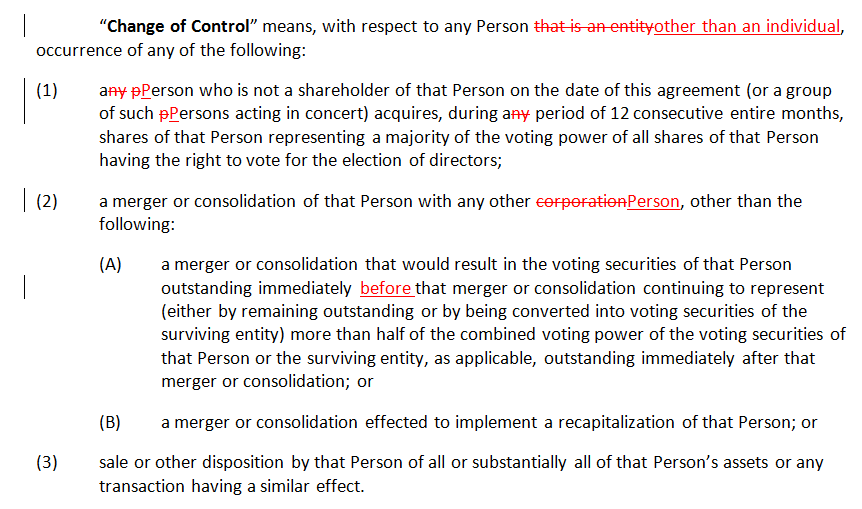

And on a related note, since I’m such a swell guy, here’s my definition of “Change of Control,” which encompasses the three forms of divestiture (it’s marked to show changes prompted by Vance’s comment):

Why not “Change in Control”? Funny you should ask; see this 2008 post. And more generally, I suspect that you could improve this definition. I invite you to give it your best shot.

I’m glad you read the case, because the passive construction renders the conclusions of the court and Stark less absurd than they would have been in an active-voice phrasing. With an active-voice sentence, an asset sale would be the only thing the contract would unambiguously *not* cover, since only the shareholder(s) can sell the company, while only the company can sell its assets.

As to your COC language, it strikes me as a bit awkward in a few places. For one thing, by using both defined and undefined “person” it’s a bit confusing. Instead of referring to a “Person that is an entity,” why not just say “entity”? For another thing, paragraph (A) is not a model of clarity when you try to parse it (plus you left out the time reference in the second line). How about this:

“a merger or consolidation by which the owners of a majority of the entity’s voting securities immediately before the transaction own a majority of the voting securities of the surviving entity immediately after it, either directly or through a chain of ownership.”

I added the last phrase thinking that you’d not want to consider a chain of control to be broken just by inserting a holding company between the pre-merger shareholders and the company. On the other hand, one could raise a substantive objection that reducing a large majority (say, one that could approve a charter change) to a lower one, without disturbing majority ownership, should still be considered a change of control.

And finally, in (3), you can dispense with the duplication by saying “by that entity of all or substantially all of its assets…”

The bottom line, of course, remains correct that the contract in the case was incompetently drafted.

Ah, nothing like being forced to read something again! Thank you. I’ve held off making your proposed changes to subclause (A): I’ll have to think more about that.

A few comments:

1/ Many of the business entities I see are limited liability companies, which, in a word, are partnerships for tax purposes, but enjoy limited liability like corporations. LLCs have ‘members’ and ‘membership interests’, not ‘shareholders’ and ‘shares’. The change of control provision under discussion seems limited to stock corporations, but I’m not sure. How would the Adams/Koven COC provision work if a specified corporation converted to an LLC and husband member sold away part or all of his membership interest in the converted entity?

2/ Change in control of a ‘person’ sounds awkward. Why not say ‘business’ or ‘company’, as long as the contract somewhere specifies that the chosen term excludes individuals?

3/ I applaud Vance’s effort to plug the holding company loophole, but ‘directly or through a chain of ownership’ makes me imagine a court saying, ‘If the drafter meant “directly or indirectly”, he would have used those words. Since he used other words, we must conclude he meant something else’. To escape that bad dream, I wonder if it mightn’t be safer to say just ‘directly or indirectly’.

Ken:

If your clause is to be in anything other than the governing documents of an entity whose law you know, I would expand on “merger or consolidation” to say “or any similar event.” For example, somewhere in Canada (Ontario maybe?) the equivalent of consolidation is amalgamation.

Chris

Ken is correct that the court never uses the phrase “asset sale,” but the full quote from the case clarifies that the court was dealing with that issue. The contract stated “if MS or any of its subsidiaries or related companies are sold.” Because a merger is not a sale, the court never needed to address whether the provision contemplated a merger. Moreover, the facts dealt with the sale of shares, another reason for the court not to mention mergers. Given that I was reciting the facts of the case, it was inappropriate for me on the Contracts Blog to go into a full exegesis on business dispositions and remind sophisticated professors that business dispositions included mergers. In fact, I chose the phrase “business disposition,” rather than sale, to use later in my analysis so that it encompassed the possibility of merger.

As a business lawyer, I’m having trouble grasping some of what went down. Even if MS sold its assets, the proceeds would belong to MS, not the husband. So really, the only way to interpret this clause would be a sale of MS shares by the husband (I did not read the decision).

But that’s one interpretation you can’t derive from the language used.

Ken- quick question on a somewhat related topic.

I’ve seen assignment clauses state – “X shall not, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY ASSIGN……..

I had a hard time figuring out what is an indirect assignment. Would putting indirectly in an assignment clause be a simple way of achieving the purposes of consent to a change of control?

“Indirectly” would make sense only if the prohibition is on assigning to specified persons, no?

Is “all or substantially all” better than “substantially all” alone?

Yes, because without all, in theory sale of all assets wouldn’t fall within the definition.

Is the point to invoke the judicial construction of “all or substantially all” in DGCL 271?

Nope.