Yesterday, Lyft issued an outlook mistakenly projecting that its margins would increase by 500 basis points. That was quickly corrected to 50 basis points. (Go here for a Bloomberg item about that.)

That mistake prompted lawyer Pat Wallen to do this LinkedIn post about it. I’ve written plenty on this topic, but given the interest generated by Pat’s post, I’ll wade in again.

This is from Pat’s post:

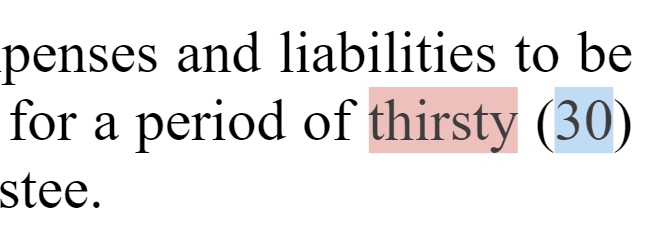

The recent screw-up at Lyft highlights why corporate lawyers use the drafting convention “[written number] (##)”.

Because when your written number differs from the numerical character, you put everyone on notice of the administrative error.

…

The error would have been apparent in this case had the SEC filing stated “fifty (500) basis points.”

This post is also responsive to those lawyers who criticize this convention in the name of efficiency.

And in a comment to his post, Pat says this:

[Y]ou may prefer a discrepancy in a contract bc procedurally that will allow for parol evidence resulting from an ambiguity, which is better than an error flowing in favor of your counterparty. The big picture is that human error is intrinsic to the contract process and parenthetical are a systemic check to that.

Pat also says that those who disagree are wrong, but this isn’t a matter of right or wrong. Instead, it’s a matter of weighing risks. I weigh the risks differently than he does. The rest of this post goes into more detail, but here’s the gist of it:

Using words and digits to state numbers can prevent errors, but it comes at a prohibitive cost.

First, it’s tedious for the reader to encounter, at every turn, numbers expressed in both words and digits. And it’s faintly ludicrous when applied to all numbers throughout a contract.

Second, in using both words and digits, you’re saying the same thing twice. That introduces a potential source of inconsistency. Even if when you first state a words-and-digits number the words and digits are consistent, they might become inconsistent as a draft is revised. So using words and digits—a convention that aims to catch an error in writing digits—introduces the potential for an additional, and entirely different, and potentially broader, kind of mistake.

Third, because it’s more likely that any inconsistency caused by revisions is due to changing digits and forgetting to change the words, rather than vice versa, applying in that context the principle of interpretation that words govern might result in a court choosing a meaning that’s contrary to what the drafter had intended. The bigger the number, the more likely that becomes.

And fourth, Pat says that using words and digits would have the benefit of allowing the disadvantaged party to argue that its meaning should apply. But in the case of inconsistent changes made in revisions, using words and digits would have created the problem, so there would be no benefit. Instead, you’d just find yourself in a dispute.

So I long ago decided that using words and digits is more of a problem than the issue it was intended to fix—digit mistakes. A better fix? Proofreading.

This discussion is limited to using the words-and-digits convention in contracts. Pat’s post was prompted by a mistake in a business document. I can’t imagine wanting the broader world to adopt this legalistic convention.

More Detail, If You Want It

Many drafters use both words and digits when stating a number, placing the digits in parentheses: six (6); five thousand dollars ($5,000); eighteen percent (18%); and so forth. This practice might have arisen because drafters noted that numbers expressed in digits are easier to read than numbers expressed in words but are more vulnerable to errors than are numbers expressed in words. Such glitches do happen. For example, in a mortgage prepared in New York in 1986, the principal amount was erroneously stated as $92,885 rather than $92,885,000. The result was “a spate of litigation, hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees, millions of dollars in damages and an untold fortune in embarrassment.” David Margolick, At the Bar; How Three Missing Zeros Brought Red Faces and Cost Millions of Dollars, N.Y. Times, 4 Oct. 1991.

In theory, combining both usages affords the immediacy of digits while providing insurance against a transposed or missing decimal point or one or more extra, missing, or incorrect digits. This insurance is reinforced by the judicial principle of interpretation that a number expressed in words controls in the case of conflict.

The words-and-digits approach has presumably saved the occasional contract party (and its lawyer) from the adverse consequences of a missing decimal point or other error involving digits, or it would have done had it been used.

But those benefits come at a prohibitive cost. It’s tedious for the reader to encounter, at every turn, numbers expressed in both words and digits. And this belt-and-suspenders approach is faintly ludicrous when applied to all numbers throughout a contract, even though lower numbers are less susceptible than are higher numbers to a significant typographical error that goes undetected. For use of words and digits in, for example, three (3) members of the board of directors to be of any benefit, those drafting and reviewing the contract would have to be particularly inattentive.

And using both words and digits violates a cardinal rule of drafting—that you shouldn’t say the same thing twice in a contract, because it introduces a potential source of inconsistency. Even if when you first state a words-and-digits number the words and digits are consistent, they might become inconsistent as a draft is revised. It’s easy to see how that can happen—digits are more eye-catching than words, so you might change the digits but forget to change the words. (The image at the top of this post offers an amusing instance of the drafting having evidently paid more attention to the digit!) So a convention that aims to catch an error in writing digits introduces the potential for an additional, and entirely different, and potentially broader, kind of mistake.

Furthermore, because it’s more likely that any inconsistency caused by revisions is due to changing digits and forgetting to change the words, rather than vice versa, applying in that context the principle of interpretation that words govern might result in a court choosing a meaning that’s contrary to what the drafter had intended.

Instead, the principle of interpretation makes sense only if a words-and-digits number features, for example, digits with a number of zeros that is inconsistent with the word version of the number, or digits with a decimal point in a place that is inconsistent with the word version of the number. In such instances, it’s more likely that the inconsistency is due to a digit glitch as opposed to a complete mismatch between words and digits.

So using words and digits is more of a problem than the issue it was intended to fix—digit mistakes.

It might seem that using words and digits for the one big number in, for example, loan documentation would be less annoying than using words and digits for all numbers in a contract. But if anything, big numbers are more prone to words-and-digits inconsistency than are smaller numbers, because the longer the words component, the less likely you are to read it. And the consequences can be particularly unfortunate. (See this 2015 blog post for an example of that.)

In closing, let’s consider Pat’s point that if you use words and digits, that has the benefit of creating confusion, allowing the disadvantaged party to argue that its meaning should apply. By contrast, with a simple digit glitch, one of the parties would just be out of luck. But in the case of inconsistent changes made in revisions, using words and digits would have created the problem, so there would be no benefit. Instead, you’d just find yourself in a dispute.

1/ It’s easy to get used to seeing every alphabetically expressed number repeated by a digital version. I find it far less irritating than, for example, nitcapping Defined Terms, for which I have spent years looking for a better way.

2/ I agree that the digital version is less likely to be wrong, so I would add an internal interpretive rule to the effect that ‘when the digital version of a number clashes with the alphabetic version, the digital version prevails’.

So, are you advocating words or digits or either?

Sorry! I neglected to restate what I recommend: words for one through ten, then digits, with obvious exceptions.