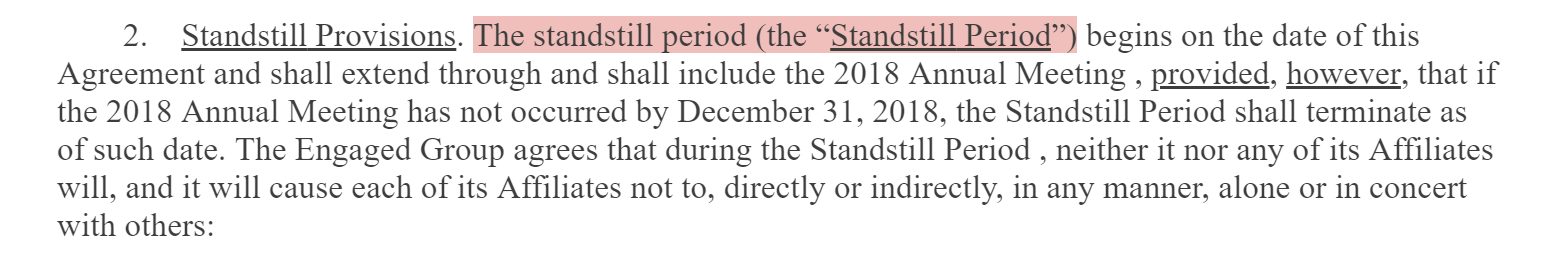

Today I tweeted this image:

The highlighted portion is of interest because the definition (The standstill period) is the same as the defined term (the “Standstill Period”). That doesn’t make sense: the whole point of defined terms is that they allow you to express a longer concept more concisely and consistently than you would otherwise. If the defined term is the same as the definition, you’re not achieving any economy. Instead, you’re adding clutter in the form of the defined-term parenthetical, and you’re forcing readers to refer to a definition that serves no purpose.

Longtime reader Art Markham chimed in:

I've got to admit – I'm kind of OK with this. It's more concise than a standalone definition, and flagging the link in this way is handy on a practical level, even if you can say it isn't necessary as a matter of pure drafting logic.

— Art Markham (@artmarkham) May 16, 2020

In other words, Art says that creating the defined term will have the effect of sending the reader back to section 2. I’m grateful to Art for making me take another look at this, but I’m not convinced by his reasoning. And generally, I’ll go for “pure drafting logic” every time :-)

What would I do? Well, I wouldn’t just delete the defined-term parenthetical. Calling the period in question the standstill period is to imbue it with meaning by proxy, given that the standstill implications are stated in the next sentence and the tabulated enumerated clauses that follow. That would be odd.

You could instead use an autonomous definition: “Standstill Period” means the period from the date of this agreement through the date of the 2018 Annual Meeting or 31 December 2018, whichever is earlier. That’s what I suggested in my tweet, but that would break up the text unnecessarily. Instead, I’d combine the two sentences into one and begin it as follows: During the period from the date of this agreement through the date of the 2018 Annual Meeting or 31 December 2018, whichever is earlier (the “Standstill Period”) ….

To return to Art’s point, my version would still result in the reader returning to section 2, but without the illogic of the current structure.

There you have it!

It strikes me that definitions like this cry out for some functional meaning rather than, or at least in addition to, merely an arbitrary slice of the calendar. Your solution works when the definition is in the same paragraph (or, as you presumptively have it, the same sentence) as the functional requirements, but not if you’re using a table of definitions (yes, yes, I know you disfavor those, but sometimes they’re unavoidable).

I’m not a fan of cross-references in a definition section, but I am a fan of the index of definitions.

I dislike standalone definitions that say “X has the meaning set forth in section N,” but I don’t see an objection to pointing to where something is fleshed out, such as “Standstill Period” means the period during which the parties refrain from certain conduct, as described in section N.” In section N you can describe both the things people will and won’t do, and set out the period during which they will and won’t do them. It might also matter whether the Standstill Period can be extended or curtailed, so that a “clinical” description, to use Wright’s phrase, could tend to get messy. And to his point more generally, I see no harm in a non-specific contextualization of the definition: when I see something defined as baldly as an arbitrary time period, my first reaction is to say, “so what?”

If, for example, ‘Force Majeure’ is defined under a clause dedicated to FM, it doesn’t need to be repeated as a definition at the head of the contract. Since the section where definitions are is where a reader would naturally go first to find the definition of a term, “X has the meaning set forth in section N,” isn’t too bad, else it might need to a lot of searching, sometimes in places within the contract that aren’t necessarily intuitive. I’m at the mo administering a contract where there are some definitions buried in the middle of the contract and not listed in the ‘Definitions’ section either – and this is a product of a ‘Magic Circle’ outfit!

I agree completely with the first sentence. If you follow Ken’s advice in MSCD, you’d have an index of definitions before the contract proper in any agreement long enough to warrant a table of contents. In shorter ones, you’d either define terms where they’re used or put more or less standard definitions in a section in the back of the contract with the other boilerplate provisions. Where “Force Majeure” belongs may depend on whether you’re creating an idiosyncratic definition for the particular deal (for example, excluding specific assumed risks), where you might prefer the in-place definition, or using a more conventional one, in which case it can ride in the caboose. If I read MSCD correctly, if you do the latter, all you need to do is use the defined term with its capital letters but no definition in the operative section, which is the clue that you’ll find the definition in the definitions section.

Vance, If I’m correctly understanding, you dislike seeing, in a ‘table of definitions’, something as coldly clinical as this:

‘Standstill Period’ means ‘the period from the signing of this agreement to the end of the 2018 Annual Meeting or the end of December 31, 2018, whichever is earlier’.

You would prefer that the definition give a clue to the function of the defined period, perhaps along the lines of ‘during which the Engaged Group will refrain from and cause each of its Affiliates to refrain from certain actions’.

I can’t see it working. It mixes the definition proper with a comment on the definition.

If a remark on a definition were deemed essential — I can’t think why it would ever be — perhaps a parenthesis after the definition would do the necessary: ‘(During the Standstill Period the agreement requires the Engaged Group to refrain from and make its Affiliates refrain from certain actions. See Section 2.)’

I think Ken’s solution is ideal, tweaked ever so slightly as follows:

‘From the signing of this agreement to the end of the 2018 Annual Meeting or the end of 31 December 2018, whichever [point] is earlier (that period, the ‘Standstill Period’).’

My tweaks, and this is a digression, flow from the belief that a period runs from point to point, and that a period running from one period to another is ill-stated.

The date of an agreement is a 24-hour period, not a point.

The ‘signing’ of an contract is a point (because it is understood as the point at which the contract takes effect, even if the process of signing takes days).

The ‘date’ of the annual meeting is a period, not a point.

The ‘end’ of an annual meeting is a point.

December 31, 2018 is a period, not a point.

The end of December 31, 2018 is a point.

If a drafter sedulously defines each period from a start point to a stop point, the choice of prepositions (‘from’, ‘to’, ‘through’) and verbs becomes unimportant.

I mention verbs because to make the end point of a period when a meeting ‘occurs’ adds needless ambiguity: has a meeting that starts at 10:00 p.m. on December 31, 2018 and ends at 2:00 a.m. on January 1, 2029 ‘occurred’ on the former date, the latter, or both? Why do that to yourself, drafter?

Finally, circling back to your mention of ‘table of definitions’: what is it? MSCD recognizes ‘definition sections’ (containing full definitions) and ‘indexes of definitions’ (containing no definitions, but stating the locations of integrated definitions, on-site autonomous definitions, and any definitions in a definitions section). Is a ‘table’ of definitions a third thing, or a variant name for a ‘section’ of definitions?

Thanks for your frequent comments on this blog. They’re always erudite and rich with practical experience. -Wright

I should have added to my comment to Ken, in referring to Wright, that I appreciate and reciprocate his appreciation. When I consider the degree of gratuitous vituperation and snark on other ostensibly serious-minded sites I read, I am deeply gratified at the rational and civilized tone maintained here.

This looks to me like a (relatively unusual) situation where drafting logically is in tension with readability and clarity. Usually, drafting logically enhances clarity, but I think the proposed alternatives would not: either (x) the definition is “too far away” from its usage in the agreement or (y) the functional passage is too complex to read easily.

That being said, my instinct would be to draft as follows: “The Engaged Group agrees that during the Standstill Period, neither it not any of its Affiliates will, and it will cause each of its Affiliates not to, directly or indirectly, in any manner, alone or in concert with others … For purposes of this Agreement, the “Standstill Period” shall mean the period beginning on the date of this Agreement and extending through and including the 2018 Annual Meeting.

You would change the on-site definition from integrated to autonomous. That’s a legitimate approach, but I think your proposed draft would place the definition after an enumerated list. Not MSCD style.

The other way is to put the definition before the use of the defined term, maybe along these lines:

‘In this agreement, the “Standstill Period” starts at signing and ends at the end of (y) the 2018 Annual Meeting or (z) 31 December 2018, whichever is earlier. During the Standstill Period, the Engaged Group shall refrain from, and cause its Affiliates to refrain from, doing any of the following, directly, indirectly, in any manner, alone, or in concert with others:….’

This approach puts the enumerated list at the end of the section or subsection.