I noted with interest Vice Chancellor Glasscock’s opinion in Weinberg v. Waystar, Inc., decided today (PDF here). Here’s the language at issue:

The Converted Units shall be subject to the right of repurchase (the “Call Right”) exercisable by Parent, a member of the Sponsor Group, or one of their respective Affiliates, as determined by Parent in its sole discretion, during the six (6) month period following (x) the (i) the Termination of such Participant’s employment with the Service Recipient for any reason … , and (y) a Restrictive Covenant Breach.

Does it mean that the call right may be exercised during the six months after termination of Weinberg’s employment or during the six months after a Restrictive Covenant Breach by Weinberg? (This was Waystar’s position.) Or may it be exercised only during the six months after occurrence of both (1) termination of the participant’s employment and (2) a Restrictive Covenant Breach by Weinberg? (This was Weinberg’s position.) The court sided with Waystar.

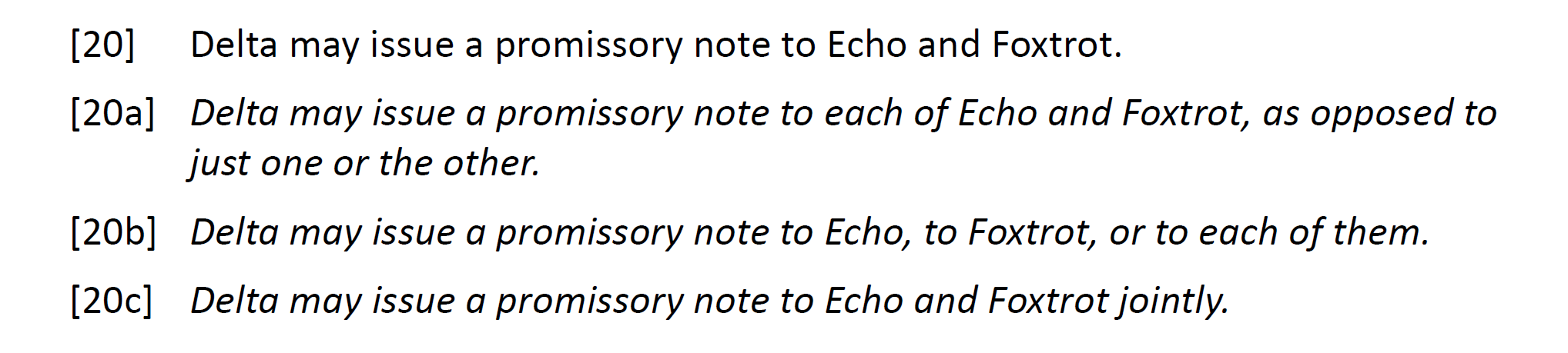

Citing a 1960 article by F. Reed Dickerson and Garner’s Dictionary of Legal Usage, Glasscock concludes that the language at issue presents the possibility of ambiguity. I agree—it is ambiguous, when considered in isolation. Here’s a roughly analogous example from MSCD, with the ambiguous sentence followed by the alternative possible meanings.

Besides that, three things come to mind.

First, unliked Dickerson and Garner, I’m not a fan of applying the labels “joint” and “several” to the ambiguity associated with and. For one thing, the conventional wisdom regarding implications of the phrase joint and several is misguided, so I find unnevering the idea of applying joint and several to other contexts by analogy. (Go here for my initial take on joint and several, in a 2012 blog post.) In the six pages I devote to and in MSCD chapter 11, I don’t use neat labels for the alternative possible meanings. Perhaps I could have, but I’ve been more focused on exploring the different ways this ambiguity manifests itself. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language doesn’t use labels in its discussion of the subject, and CGEL co-author Rodney Huddleston didn’t recommend that I use labels (see this post about how Rodney helped me with ambiguity), so I’ve been OK doing without labels.

Second, this portion of the opinion caught my eye (footnotes omitted):

Professor Dickerson is not the only scholar to assert that the “several” meaning of “and” is commonplace. Indeed, Professor Bryan A. Garner agreed in his Dictionary of Legal Usage that “[t]he meaning of and is usually several.” Moreover, at least one court has agreed that “[w]hen the word ‘and’ is used in a permissive sentence, it is likely to be used in its several sense.”

For purposes of understanding structural ambiguity of this sort, I’m leery of broad generalizations regarding the likelihood of a given possible meaning. The whole point of ambiguity is that you can’t tell, in isolation, which meaning is the “right” meaning. It’s only when you deal with individual examples and can take context into account that you have a chance of determining which reading make more sense. Talk of likelihood smacks of “canons of construction,” which are arbitrary rules courts make up to help them deal expeditiously with disputes over ambiguity. There might be a place for some canons of construction, but if you confuse them with understanding the natural meaning of prose, you’re screwed. That’s something courts have a hard time understandings; see this January 2022 post.

And third, this paragraph of the opinion (footnotes omitted) follows right after the extract quoted above:

Applying these principles to the Call Right provision supports Waystar’s interpretation. The Call Right provision is permissive: Waystar may exercise it “in its sole discretion.” It is thus natural to read the word “and” in its “several” sense, to mean that Waystar can exercise the Call Right during “the six (6) month period” following Weinberg’s “Termination . . . for any reason,” during “the six (6) month period” following “a Restrictive Covenant Breach,” or both. This comports not only with the sources referred to above; more importantly, it complies with a colloquial understanding of English as commonly used. “You can take a doughnut, a danish, and a bagel” invites, but does not mandate, gluttony.

I suggest that doesn’t make sense. Sure, Waystar gets to decide whether it wants to exercise the call right, but that’s unrelated to interpreting restrictions on when it could be exercised. And the pastry analogy is irrelevant. What matters most in making sense of ambiguity is what context can tell us. That’s what the court gets to next.

The awkward reality is that judges are dilettantes when it come to this kind of ambiguity. That’s because it’s gruesomely subtle, the stuff of linguistics. It’s only thanks to Rodney Huddleston’s help that I avoided making a fool of myself. Someday I’d like to offer training to court personnel. That’s something I discuss in this August 2020 blog post, entitled, cheerily, Many Judges Are Bad at Textual Interpretation. What Do We Do About It?

Working solely from the quoted contract language, here’s my take. The relevant language can be boiled down to this:

A may repurchase the converted units during the six-month period after x (termination) has occurred and y (breach) has occurred.

That means A may repurchase within six months after the point at which x and y have both occurred, which can only mean when the later occurs (if they are not simultaneous). The occurrence of only one and not the other does not trigger the start of a repurchase period.

Pretending that “and” means “or” creates two six-month periods and leaves unsaid whether the passage of the earlier period without repurchase extinguishes A’s repurchase rights or leaves open the possibility that A will have another repurchase right during the later period, if any.

Once the parties decide which of three potential meanings they want, drafting a corresponding provision is no great feat. Here are the three possible meanings I see:

1/ A single repurchase period starting when x and y have both occurred (=when the later occurs);

2/ Two potential repurchase periods, but the passage of the earlier extinguishes the later, so only one period can ever take effect; and

3/ Two potential repurchase periods, but the passage of the earlier has no effect on the later, so both periods could take effect. –Wright

Sorry, I haven’t yet had time to look closely at this.